[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between ]

Women of 1973

Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between

The initial assignment for Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between was to explore Watergate, the impact of the scandal, its disinformation and fraught political rhetoric on first-time voters, teens, and American families. I’d already done the same in my other two “docudrama” novels about McCarthyism (Suspect Red) and Cold War Berlin (WALLS), creating “everyman” characters on opposite sides of the political spectrum coming to understand and respect one another, despite what their “tribe” told them. The connecting tissue among all three of these novels (set in 1953, 1961, and 1973)? The trickle-down influence of herd mentality, inflammatory innuendo and labels, fear, propaganda, and a pitched battle between truth and lies, our willingness (or not) to listen to and confront harsh truths.

How did that kind of milieu affect young adults’ world view, relationships, self-definition, and expectations for themselves? How would it affect the future of our nation?

I began researching, deciding to home in on 1973, the year of the Senate Watergate committee hearings. About the same time a beautifully-acted and disturbing bio-pic series aired, Mrs. America—about Phyllis Schlafly and her STOP ERA crusade of homemakers who rose up against the feminist movement and the ERA’s momentum. Seeing it, my editor and I realized that 1973 was also the year that the ERA was working its way toward ratification, state by state, and meeting unexpected opposition from frightened women. (For more on that, please see the ERA section.)

It became clear this novel had to be about both those momentous things, as much about the fight for women’s freedoms as the struggle for fact and decency in our politics. And the questions about us as a people they raised.

At first, I worried combining two such enormous and separate political groundswells, albeit simultaneous, would seem contrived. But I soon found women who were legitimately connected to both and/or whose professionalism made them personifications of feminist goals. They became my factual linchpins in the photo essays as well as influences on my main characters Patty and Simone.

Rather amazing women. I’d like to share brief bios of them—these women who played critical roles in the events of 1973 and who appear in the pages or are mentioned by my characters in Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between. (Please read the novel for more!):

One of the greatest pleasures in writing Truth, Lies was interviewing Jill Ruckelshaus. She was incredibly generous with her time, in sharing her vast wisdom hard-won from fifty-plus years advocating for women’s equality and reproductive rights, and in her enduring hope in the power of women uniting for common good—no matter their party affiliation or background.

One of the greatest pleasures in writing Truth, Lies was interviewing Jill Ruckelshaus. She was incredibly generous with her time, in sharing her vast wisdom hard-won from fifty-plus years advocating for women’s equality and reproductive rights, and in her enduring hope in the power of women uniting for common good—no matter their party affiliation or background.

In a 1972 article about the surprising and influential presence of female delegates at the Republican convention nominating Nixon for re-election, Time magazine described Ruckelshaus as a “soft-spoken” woman, the “Republicans’ answer to Gloria Steinem.” One gets the sense that such comments on her bearing and appearance—(that she was “pert and pretty,” had “Windex-blue eyes,” an ability to charm naysayers, and was the antithesis of a “noisy libber”)—annoyed Ruckelshaus but she tolerated them to get the job done. “Why bother poking a pig?” she recently said. “I found noisy voices and agitation were needed to start the conversation and quieter ones to bring consensus.”

In many ways, as a well-educated, moderate Republican with a post-graduate degree from Harvard, a mother of five, she was the most unimpeachable voice against Phyllis Schlafly’s claims that feminism and the ERA were undoing the traditional American family.

She’d moved to the Washington area in 1969, when her husband Bill became the first head of the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). Her suburban Maryland kitchen quickly became a gathering spot for NWPC strategizing, as her young children darted about. Word of mouth grew their numbers—which is exactly how my fictional character Aunt Marjorie (the godmother of my protagonist Patty) could hypothetically meet the iconic feminist and get involved in supporting the ERA. That allowed Jill Ruckelshaus to become a never-seen but wonderful influence on my characters—especially Patty and her mother who had a longer journey to take to reach self-redefinition.

By 1973, Ruckelshaus had become White House Special Assistant on Women’s Rights, working to improve the horrendous statistic that only three percent of all elected and appointed jobs were filled by women. She chose to give up the position, however, after her husband, then the Deputy Attorney General, resigned in protest during the infamous Saturday Night Massacre and Nixon’s demand that he fire the Watergate Special Prosecutor.

That did not stop Jill Ruckelshaus’ advocacy and activism. Gerald Ford made her head of his Presidential Commission on Women’s Rights and in 1980, Democrat Jimmy Carter would appoint her to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. Later that year, at the Republican National Convention that nominated Ronald Reagan as the Republican candidate for president and withdrew its longstanding support of the ERA, she led a march of 4,500 ERA supporters to protest that policy change. She told a reporter: "My party has endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment for 40 years. Dwight Eisenhower endorsed ERA. Richard Nixon endorsed ERA. Gerald Ford endorsed the ERA. But something happened in Detroit last week. Give me back my party."

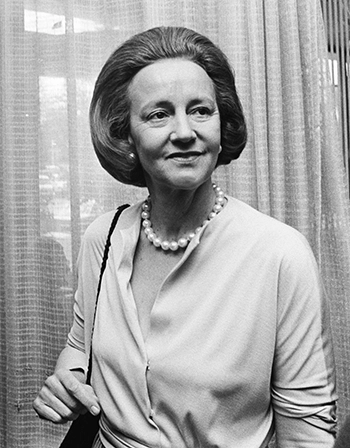

Katharine Graham: It’s not a stretch to speculate that without The Washington Post’s quiet but steely publisher the country may never have known the full truth of Watergate, the scandal slipping into obscurity as the nonsensical “3rd rate burglary” the White House painted it as being. Woodward and Bernstein did the legendary reporting, Ben Bradlee the editing—but the reports would never been printed without Graham braving the ire of a president known to be singularly vindictive about “screwing his enemies” and the very personal and vile threat Nixon’s campaign director, John Mitchell, made against her.

Katharine Graham: It’s not a stretch to speculate that without The Washington Post’s quiet but steely publisher the country may never have known the full truth of Watergate, the scandal slipping into obscurity as the nonsensical “3rd rate burglary” the White House painted it as being. Woodward and Bernstein did the legendary reporting, Ben Bradlee the editing—but the reports would never been printed without Graham braving the ire of a president known to be singularly vindictive about “screwing his enemies” and the very personal and vile threat Nixon’s campaign director, John Mitchell, made against her.

She’d already stood up to the White House two years earlier, printing sections of the Pentagon Papers even after Nixon's administration put an injunction stopping The New York Times from circulating the damning report on the Vietnam War. But printing excerpts of the report was a more clear-cut risk, standing up for first amendment rights. Watergate’s details were murky at first, disconnected and —given Nixon’s overwhelming win in the 1972 presidential election—so implausible few believed them. The Post was overwhelmingly denounced. “If we hadn’t been right, we’d have been dead,” Graham said matter-of-factly.

Bernstein still chokes up relating this anecdote: After he and Woodward reported that Mitchell -- while the acting attorney general -- had controlled a secret Republican party fund used to finance clandestine political espionage against Democrats during the 1972 campaign, a subpoena server arrive at the Post's offices. Sent by CR(EE)P, the Committee to Re-Elect the President, he demanded the reporters' notes. Bradlee called Graham, who responded that Bernstein's notes were not his to turn over. As owner of the paper, the notes were hers. Therefore, if anyone was going to jail, it would be she. The subpoena server left empty-handed. Never to return.

Being a warrior for truth was not a role Graham had ever expected to play. She had only inherited the reins of her family’s newspaper a few years earlier, after her husband died. But she more than rose to the daunting responsibility. The first 20th-century female publisher of a major American newspaper and the first woman Fortune 500 CEO, Graham was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Republican George W. Bush. Her memoir, Personal History, won a Pulitzer Prize for her candid portrayal of both her husband’s mental illness and suicide and her personal journey through the momentous change in women’s roles that the fight for the ERA brought.

Frankly, there are no more resonant icons for females proving women’s capabilities during and connected to Watergate than Katharine Graham and Jill Wine-Banks, the only female lawyer on the Watergate special prosecutor staff. At that time only four percent of American attorneys were women. Wine-Bank’s savvy cross-examination that caught Nixon’s secretary in a jaw-dropping lie as she gave sworn testimony—about the cause of an 18 ½ minute erasure in one of Nixon’s taped conversations—is a touchstone that made all the difference in the nation’s understanding that a “third-rate burglary” had evolved into a conspiracy—a series of calculated moves to hide wrongdoing. A moment loyal “Nixonites” began to break from blind loyalty.

Frankly, there are no more resonant icons for females proving women’s capabilities during and connected to Watergate than Katharine Graham and Jill Wine-Banks, the only female lawyer on the Watergate special prosecutor staff. At that time only four percent of American attorneys were women. Wine-Bank’s savvy cross-examination that caught Nixon’s secretary in a jaw-dropping lie as she gave sworn testimony—about the cause of an 18 ½ minute erasure in one of Nixon’s taped conversations—is a touchstone that made all the difference in the nation’s understanding that a “third-rate burglary” had evolved into a conspiracy—a series of calculated moves to hide wrongdoing. A moment loyal “Nixonites” began to break from blind loyalty.

Today a much-quoted legal analyst and co-host of the podcast Sisters-in-Law, Wine-Banks recounts in Watergate Girl what it was like to be a skilled but young and attractive woman in the national spotlight, infantilized by the press as the “mini-skirted bombshell.” At one point during the 30-year-old’s razor-sharp questioning of Rose Mary Woods—when the secretary’s response was particularly hostile and heated—Judge Sirica reflexively chided them both, “All right, we have enough problems without two ladies getting into an argument.” Wine-Banks managed to maintain her cool despite the judge's sexist comment and the resulting spectator laughter. Such was the requirement to always be “ladylike” in 1973.

Interestingly, Wine-Banks’ home was burglarized—twice—during her stint as a Watergate prosecutor. The second time, after Woods’ testimony, the police called in the FBI. The agents informed Wine-Banks they could tell that a bug had been removed from her telephone during that break-in.

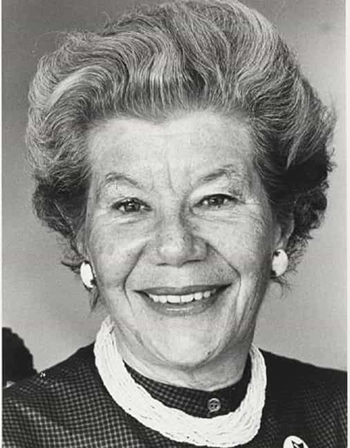

Martha Mitchell: The tapestry of Watergate is thick with a vast multitude of players, major and minor, and some non-political issues threaded throughout. Attorney General Mitchell’s wife, the vivacious and colorful “Mouth of the South,” Martha was legendary for her gossipy, late-night telephone calls and purposefully shocking soundbites. An ardent campaigner for Nixon, a frequent guest on talk shows and Laugh-In, Martha called White House reporter Helen Thomas immediately following the Watergate break-in to say the administration was trying to silence her. During the call, Thomas heard a scuffle and then the phone went dead. Martha would later claim she was held down and drugged by her husband’s protective detail. One of those men was a former FBI agent, who always denied the incident and went on to become an ambassador in the Trump administration.

Martha Mitchell: The tapestry of Watergate is thick with a vast multitude of players, major and minor, and some non-political issues threaded throughout. Attorney General Mitchell’s wife, the vivacious and colorful “Mouth of the South,” Martha was legendary for her gossipy, late-night telephone calls and purposefully shocking soundbites. An ardent campaigner for Nixon, a frequent guest on talk shows and Laugh-In, Martha called White House reporter Helen Thomas immediately following the Watergate break-in to say the administration was trying to silence her. During the call, Thomas heard a scuffle and then the phone went dead. Martha would later claim she was held down and drugged by her husband’s protective detail. One of those men was a former FBI agent, who always denied the incident and went on to become an ambassador in the Trump administration.

Much has been made recently of Martha’s tragic life story. Julia Roberts played her in the 2022 mini-series Gaslit. Following her claims that Nixon had to have okayed the cover-up and his campaign’s other political espionage—long before there was any kind of connection made to the White House—Martha was smeared by Nixon’s people as “crazy,” overwrought and confused and not to be believed—a disparaging label sadly common in the 1970s for women who insisted on saying “troublesome” things or appeared upset when they said them.

I bring her into Patty’s story briefly, in Chapter Three, to further embroider the novel’s backdrop of contemptuous, sexist attitudes about women’s acumen and “emotionality” that feminists were fighting and women like Patty’s mother, Dot Appleton, would be trapped in.

With Martha, her well-known love for a cocktail didn’t help. But she kept talking—at first trying to protect her husband as it became clear to her that Nixon would turn on his old friend and law-partner to pin the break-in’s planning on him. She was, of course, correct—as John Dean revealed during his testimony—that Mitchell was to be scapegoated for the break-in and campaign dirty tricks, Dean for the coverup.

When Martha died in 1976, alone, ravaged by cancer, someone planted an enormous banner of flowers at her graveside funeral that spelled out: “Martha Was Right.” And the psychology field coined a term, “the Martha Mitchell effect,” to describe a professional mistakenly dismissing—as delusional—a patient’s seemingly paranoid but totally correct perceptions of real events.

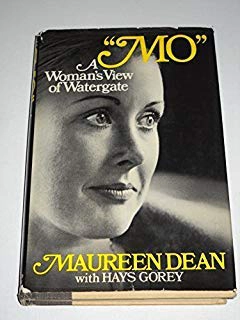

Maureen Dean stood by her husband John as he testified before the Senate and the nation, as he was convicted of obstructing justice, and as he served four months of a four-year prison sentence (granted leniency for his cooperation with the Watergate Special Prosecutor). In October 2022 they celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary. She co-wrote the screenplay for a 1979 mini-series based on her husband’s book, Blind Ambition, starring Martin Sheen. Maureen also penned two novels, Washington Wives and Capitol Secrets.

Maureen Dean stood by her husband John as he testified before the Senate and the nation, as he was convicted of obstructing justice, and as he served four months of a four-year prison sentence (granted leniency for his cooperation with the Watergate Special Prosecutor). In October 2022 they celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary. She co-wrote the screenplay for a 1979 mini-series based on her husband’s book, Blind Ambition, starring Martin Sheen. Maureen also penned two novels, Washington Wives and Capitol Secrets.

Her husband became an investment banker, frequent television commentator, and bestselling author of eleven nonfiction books. John Dean has often shared that as “Mo” helped type his 60,000-word statement for the Senate hearings and learned all the illegalities the White House staff engaged in, she vehemently declared that if they had only told their wives first, none of it would have happened. The women would have talked sense into them.

During Watergate, Washington had two newspapers, morning (the Post) and evening (The Star). Mary McGrory was a Star columnist, winning a Pulitzer Prize for her witty, adroit commentary that so aggravated Nixon, she became the only woman on his primary “enemies list.” Coincidentally or not, she was subjected to an invasive IRS audit, a retribution Nixon was caught on tape suggesting be done to his critics.

During Watergate, Washington had two newspapers, morning (the Post) and evening (The Star). Mary McGrory was a Star columnist, winning a Pulitzer Prize for her witty, adroit commentary that so aggravated Nixon, she became the only woman on his primary “enemies list.” Coincidentally or not, she was subjected to an invasive IRS audit, a retribution Nixon was caught on tape suggesting be done to his critics.

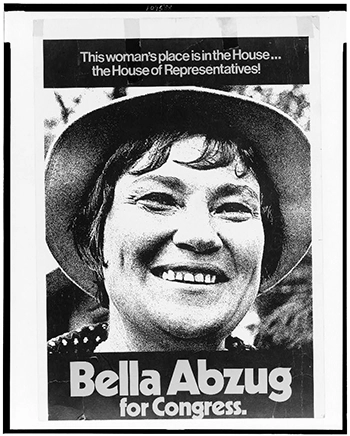

Feminist lawyer and activist, an organizer of the 1970 Women’s Strike for Peace and Equality and platform battles for the ERA at the Democratic National Convention, and a NWPC cofounder, Bella Abzug was a formidable, boisterous, and omnipresent national figure throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. ''She's fierce and intense and funny,'' said her friend and ally, Gloria Steinem. ''When she argues with you, it's because she takes you seriously.'' As a congresswoman representing New York (1971-1977), Abzug spearheaded the bill declaring an annual Women’s Equality Day, authored legislation stopping credit companies from denying a woman’s application for a loan or credit card unless her husband or father co-signed, and pushed for abortion rights and programs to support working women, like national daycare. Her nickname “Battling Bella” fit her as well as did her signature wide-brim hats that she began wearing as a young attorney representing union workers—so her opposing counsel would not mistakenly assume she was a secretary there to take notes.

Feminist lawyer and activist, an organizer of the 1970 Women’s Strike for Peace and Equality and platform battles for the ERA at the Democratic National Convention, and a NWPC cofounder, Bella Abzug was a formidable, boisterous, and omnipresent national figure throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. ''She's fierce and intense and funny,'' said her friend and ally, Gloria Steinem. ''When she argues with you, it's because she takes you seriously.'' As a congresswoman representing New York (1971-1977), Abzug spearheaded the bill declaring an annual Women’s Equality Day, authored legislation stopping credit companies from denying a woman’s application for a loan or credit card unless her husband or father co-signed, and pushed for abortion rights and programs to support working women, like national daycare. Her nickname “Battling Bella” fit her as well as did her signature wide-brim hats that she began wearing as a young attorney representing union workers—so her opposing counsel would not mistakenly assume she was a secretary there to take notes.

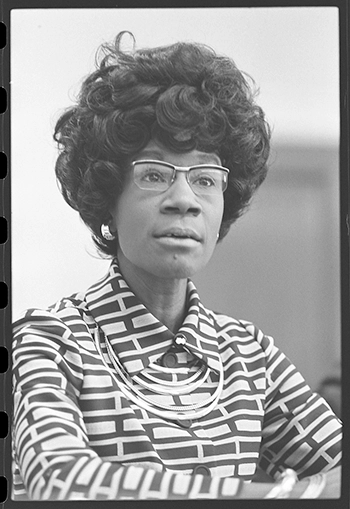

The first Black woman elected to the U. S. House of Representatives, Shirley Chisholm served six terms from 1969 to 1983, introducing more than 50 pieces of legislation. In 1972, she became the first woman to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. During that campaign she was initially blocked from participating in televised primary debates. After suing, she was permitted one speech. Even so, despite those hurdles and a surprising lack of support from the male-dominated Congressional Black Caucus, Chisholm entered twelve primaries and won an impressive 10 precent of delegates to the national convention.

The first Black woman elected to the U. S. House of Representatives, Shirley Chisholm served six terms from 1969 to 1983, introducing more than 50 pieces of legislation. In 1972, she became the first woman to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. During that campaign she was initially blocked from participating in televised primary debates. After suing, she was permitted one speech. Even so, despite those hurdles and a surprising lack of support from the male-dominated Congressional Black Caucus, Chisholm entered twelve primaries and won an impressive 10 precent of delegates to the national convention.

A pioneer in countless ways, Chisholm was a tireless crusader against the double discrimination of race and gender facing Black women, cofounding the National Political Congress of Black Women after she retired from the House. At the 20th anniversary gathering of the NWPC, which she also helped found, Chisholm urged the younger attendees to carry on the fight for all women: “We did the best to our abilities, in spite of snide remarks and epithets muttered about us. We knew we were about the business of bequeathing a legacy for future generations to come. You are here today to carry it on.”

Author Betty Friedan is often referred to as the mother of the 1960s women's movement. She had a lot of help! But her gut-wrenchingly honest book, The Feminine Mystique, was indeed the explosive treatise that ignited countless women’s epiphanies about their frustrations, aborted hopes, and inherent right to have the same opportunities as men. In 1973, in a New York Times Magazine article celebrating its tenth anniversary, Friedan recounted the origins of the book that rocked the world of American housewives—a survey of her Smith College classmates of 1942. “Each of us thought she was a freak if she didn't experience that mysterious orgiastic fulfillment waxing the kitchen floor as the commercials promised... if we still had ambition, ideas about ourselves as people in our own right—well, we were simply neurotics, and we confessed to priest or psychoanalyst.”

Author Betty Friedan is often referred to as the mother of the 1960s women's movement. She had a lot of help! But her gut-wrenchingly honest book, The Feminine Mystique, was indeed the explosive treatise that ignited countless women’s epiphanies about their frustrations, aborted hopes, and inherent right to have the same opportunities as men. In 1973, in a New York Times Magazine article celebrating its tenth anniversary, Friedan recounted the origins of the book that rocked the world of American housewives—a survey of her Smith College classmates of 1942. “Each of us thought she was a freak if she didn't experience that mysterious orgiastic fulfillment waxing the kitchen floor as the commercials promised... if we still had ambition, ideas about ourselves as people in our own right—well, we were simply neurotics, and we confessed to priest or psychoanalyst.”

She cited the fact that in 1963 nearly half of all women in the United States were already “committing the unpardonable sin of working outside the home to help pay the mortgage or grocery bill . . .Betraying their femininity, undermining their husband's masculinity, and neglecting their children by daring to work for money at all—no matter how much it was needed. They couldn't admit, even to themselves, that they resented being paid half what a man would, being passed over for promotion, or writing the paper for which he got the degree and the raise.”

She urged women to beware the untruths told by the STOP ERA crusade, to not be frightened by independence, and to not resort to alienating “man-hate” rhetoric. To her “men were fellow victims, suffering from an outmoded masculine mystique which made them feel unnecessarily inadequate when there were no bears to kill.”

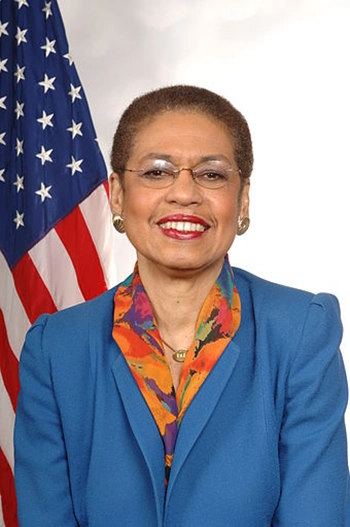

Most will remember Nora Ephron as the witty screenwriter of romantic comedies When Harry Met Sally or You’ve Got Mail, but her earlier career was as a searingly blunt columnist, writing poignant and pointed essays about the condition of womanhood. She, too, was a trailblazer. She worked briefly at Newsweek, when women were not allowed bylines of their own, serving as researchers for the exclusively male reporting staff. She participated in a 1970 class action lawsuit against the newsmagazine—spearheaded by civil-rights attorney and equal pay activist Eleanor Holmes Norton—to push the publication to allow women to be reporters themselves.

Most will remember Nora Ephron as the witty screenwriter of romantic comedies When Harry Met Sally or You’ve Got Mail, but her earlier career was as a searingly blunt columnist, writing poignant and pointed essays about the condition of womanhood. She, too, was a trailblazer. She worked briefly at Newsweek, when women were not allowed bylines of their own, serving as researchers for the exclusively male reporting staff. She participated in a 1970 class action lawsuit against the newsmagazine—spearheaded by civil-rights attorney and equal pay activist Eleanor Holmes Norton—to push the publication to allow women to be reporters themselves.  Ephron went on to write for the New York Post and Esquire magazine. In a Watergate connection, she was briefly married to Carl Bernstein.

Ephron went on to write for the New York Post and Esquire magazine. In a Watergate connection, she was briefly married to Carl Bernstein.

Ephron’s wonderful essays, her droll observations on things like body image and cultural stereotyping/expectations—which unnervingly still ring so true today—would certainly have fueled the ideas of a liberal teen like Simone and startled conservatives like Patty into rethinking society-dictated definitions of worth and femininity.

Holmes Norton was also a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus and the National Black Feminist Organization. President Jimmy Carter would appoint her the first woman head of the EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) and in 1991 she was elected to Congress as the District of Columbia’s delegate. She is currently serving her 16th term on Capitol Hill.

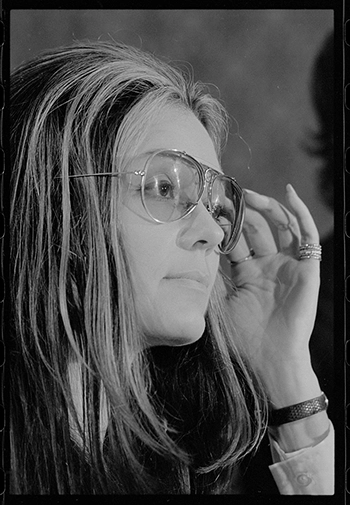

At this writing, the legendary feminist, activist, and author of a half dozen empowering and eye-opening books, a NWPC cofounder, founding editor of Ms. Magazine, and winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Gloria Steinem is 90 years old. She is still speaking, still urging unity among women as the way to achieve rightful change. At the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, half a million people hushed to hear her impassioned words: “Thank you for understanding that sometimes we must put our bodies where our beliefs are. Sometimes pressing send isn’t enough.

At this writing, the legendary feminist, activist, and author of a half dozen empowering and eye-opening books, a NWPC cofounder, founding editor of Ms. Magazine, and winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Gloria Steinem is 90 years old. She is still speaking, still urging unity among women as the way to achieve rightful change. At the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, half a million people hushed to hear her impassioned words: “Thank you for understanding that sometimes we must put our bodies where our beliefs are. Sometimes pressing send isn’t enough.

“Remember the constitution does not begin with ‘I, the president.’ It begins with “We, the people.’ So don’t try to divide us . . . We will not be quiet, we will not be controlled . . . God may be in the details, but the goddess is in the connections . . . Make sure you introduce yourselves to one another and decide what we’re going to do tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.”

For a timeline of feminist achievements and battles during 1973, see this detailed write-up from the Feminist Majority Foundation