[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between ]

Vietnam

Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between

The Vietnam War and its seismic impact on American families and politics, the “generation gap” and cultural divide it wrought—is one of several subplots/themes in Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between. By the beginning of 1973, the Nixon administration had finally agreed to the Paris Peace Accords. Our fighting troops and long-held POWs started coming home.

The Vietnam War and its seismic impact on American families and politics, the “generation gap” and cultural divide it wrought—is one of several subplots/themes in Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between. By the beginning of 1973, the Nixon administration had finally agreed to the Paris Peace Accords. Our fighting troops and long-held POWs started coming home.

One of my supporting characters, Will, faces the devastation so many Americans had to grapple with—a beloved brother returning, completely changed by his combat experiences. To be an authentic tapestry, that kind of heartbreak and challenge had to be woven into the narrative. And honestly, the scenes with Will turned out to be some of the most poignant I wrote, as well as critically important to my sheltered protagonist, Patty, growing in empathy and understanding of others.

I also recount briefly in the novel’s Prologue photo essay how the war helped elect Nixon in 1968:

That year—amid escalating anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, protests following Martin Luther King Jr.'s tragic assassination, and a chaotic Democratic convention and demonstrations outside in Chicago—Republican presidential candidate Nixon promised a return to “law and order” and to bring the war to an honorable end. A frightened America, unnerved by the violence, narrowly elects him by a mere 1% of the popular vote.

But Nixon doesn't end the war quickly. In fact, his Vietnam policies will ultimately cost the lives of 22,000 more Americans.

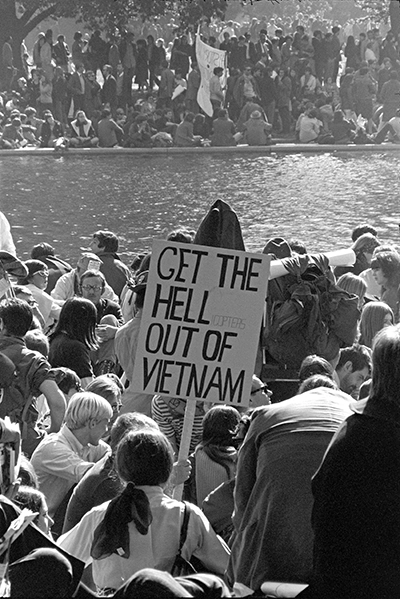

By 1970, five years into the war and one year into Nixon’s first administration, young Americans are frustrated and angry. Peaceful flowerchild protests haven't worked. Young men live in dread of their birth date being pulled out of a plastic container on TV to be drafted to fight a war that has dragged on and on and which they don't believe in. Horrific scenes of battles and injured Vietnamese civilians flood American homes each night in network news.

Sit-ins and rallies on college campuses grow more rebellious. At this point most polled Americans agree the Vietnam War was a mistake. But the majority remained critical of the students antiwar movement, many adults damning them as spoiled ingrates or debauched hippies. Nixon fuels their resentments, calling students who disrupt campuses “bums.”

The country is a tinderbox.

April 1970: Nixon announces withdrawal of 150,000 American troops only to follow that ten days later with the news he’s expanded the fight into Cambodia “to clean out enemy sanctuaries.” The United States cannot act like “a pitiful giant,” he says, adding, “we will not be humiliated.”

College campuses erupt. Protests lead to the horrific events of Kent State and the tragic deaths of four undergraduates, the wounding of nine more, when the National Guard fires into a crowd of student protesters.

In horrified reaction, students at 400-plus colleges and high schools go out on strike and thousands of sympathetic adults join their marches. Some turn destructive. Within days comes another tragedy: two more innocent students killed at Jackson State when police—mistakenly thinking a sniper is inside—fire into a dormitory.

In New York City, aggravated by what they feel are “longhair” “draft-dodgers” and “potheads,” construction workers attack student protestors with crowbars and planks of wood in what becomes known as the “Hard Hat Riots.”

Nixon taps into this growing grievance among blue-collar workers, whom he dubs “the great silent majority.” Their fear of cultural changes, their sense of being left behind and replaced—from civil rights to “dove” anti-war sentiments to the feminist movement.

Traditionally a Democratic voting bloc, they swing hard to the right in 1972, casting their votes overwhelmingly for Nixon. Despite the growing Watergate scandal and the release of the Pentagon Papers, revealing the many lies told by various administrations—including Nixon’s—that kept Americans fighting even after it became obvious that a conclusive victory in that war was impossible.

Nixon wins in a landslide.

That is a bareboned synopsis of what was one of the most controversial and redefining moments in our history. To learn more, there are dozens of books, movies, and documentaries about the Vietnam War. These are just a few recommendations:

The Vietnam War

The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

The Vietnam War: the Definitive Illustrated History (DK and the Smithsonian Institute)

The Vietnam Reader (a collection of fiction, nonfiction, songs, poems, photography)

Edited by Stewart O’Nan

The Vietnam War by Geoffrey Ward and Kenneth Burns

And Burn’s PBS series:

https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-vietnam-war

Kent State

67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence by Howard Means

Kent State by Deborah Wiles

https://www.britannica.com/event/Kent-State-shootings

https://www.library.kent.edu/special-collections-and-archives/kent-state-shootings-may-4-collection

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20240503-kent-state-university-1970-protests-that-shook-the-us

1968

1968 by Michael T. Kaufman, A New York Times Book

1968: The Year that Rocked the World by Mark Kurlansky

Playing with Fire: the 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics

by Laurence O’Donnell

a CNN series: 1968: The Year that changed America