[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between ]

The ERA

Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

24 simple words. Some might even say a no-brainer in a democracy promising justice for all. Equality of opportunity, pay, individual freedoms, and choice, for women and men, for all. Yet, somehow, codifying the Equal Rights Amendment has proved anything but simple.

First introduced to Congress in 1923, three years after American women were finally granted the right to vote, the ERA languished for decades. Then come 1970, the women’s liberation movement had gained real political traction, led by feminist groups like NOW (the National Organization for Women), activist-authors Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, speechwriter and a cofounder of the NWPC (National Women’s Political Caucus) Jill Ruckelshaus, Congresswomen Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm, and civil rights attorneys Flo Kennedy and Eleanor Holmes Norton, among many others (see section Women of 1973 for more about these trailblazers).

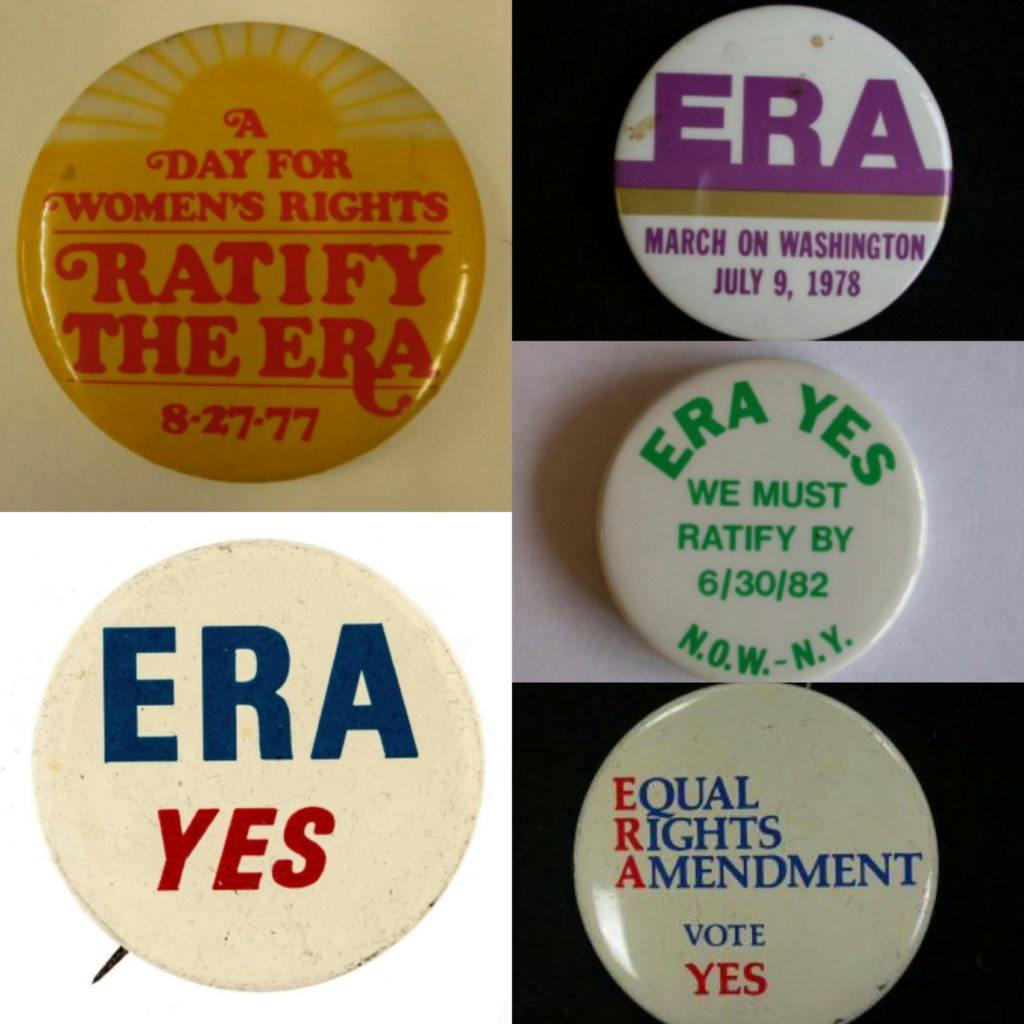

In February of that year, NOW members picketed the U.S. Senate when a subcommittee was discussing lowering the voting age to 18. They demanded Congress reopen hearings on the ERA. Then, on August 26th, 1970—the 50th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment—women flooded the streets in over 40 cities for a nationwide “Women’s Strike for Equality." In New York City, an estimated 50,000 women shut down Fifth Avenue. Carrying signs like: "Don't iron while the strike is hot," the protestors demanded equal opportunities in education and employment, free childcare, and legal access to abortion. Many homemakers joined in as well, refusing to clean or cook that day. As never before, women seemed united.

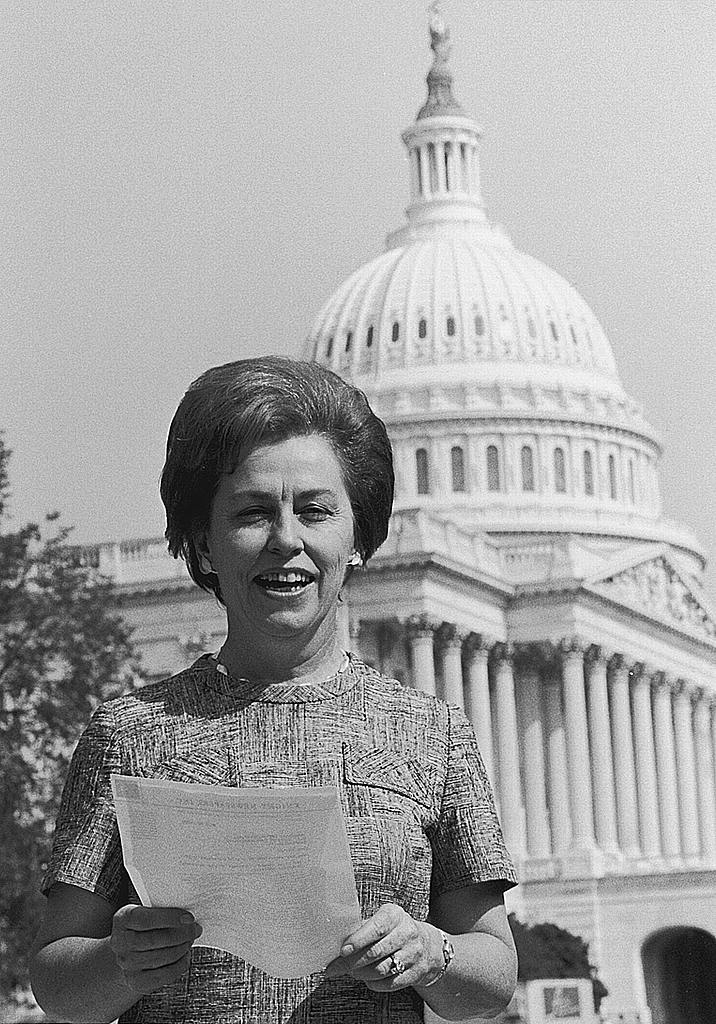

Riding the success of that march and “second wave feminism,” Congresswoman Martha Griffiths (D-MI) managed to wrestle the ERA out of the House Judiciary Committee—which had refused for decades to even hold hearings on the measure. She used a rarely tried procedural tactical—a discharge petition to yank a bill out onto the floor for the full House to hear and discuss. The release required a majority to sign it. Even though only one of 12 females among the 435 House members, Griffith managed to convince and cajole the needed numbers, helped by Republican leader Gerald Ford.

Sadly, Griffiths is little remembered today, overshadowed by more famous feminists, but many historians and news organizations of the day, like The Guardian, attributed its passage in Congress to her “implacable determination, a lawyer’s grasp of procedural niceties, and a tongue like a blacksmith’s rasp.” Note, of course, The Guardian’s backhanded compliment about Griffiths’ sharp, “less than feminine” debate style.

Griffiths re-introduced the ERA, and after some contentious debate, her H.J. Res. 208 was adopted by the House on October 12th, 1971, with a resounding bipartisan 354 yeas to 24 nays.

Five months later in March 1972, the Senate also adopted the ERA with overwhelming support from both parties and a stunning vote of 84 to 8. Within 48 hours Hawaii, Delaware, New Hampshire, Iowa, and Idaho had ratified, followed quickly by other states across the country. By the end of one year, 30 states had affirmed. Only eight more were needed to reach the required 38.

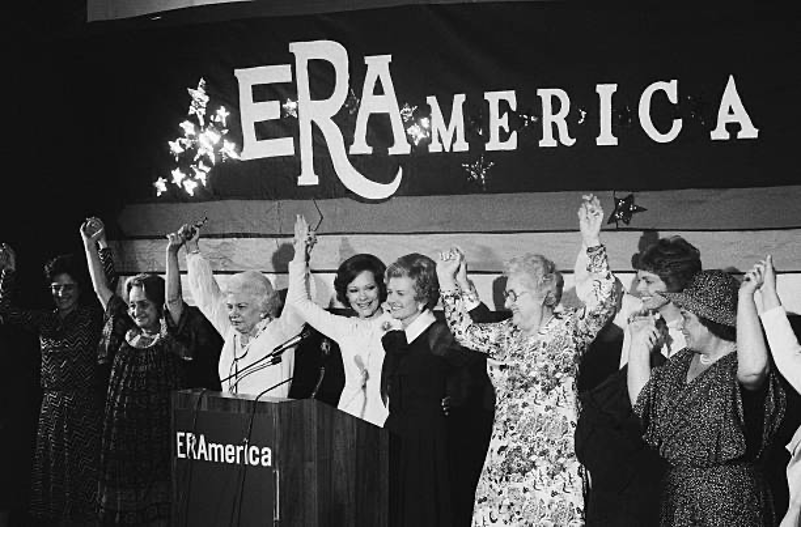

At 1973’s dawning, feminists and their male allies—and there were many at that time, including a majority of Republicans—rejoiced. Final ratification before the 1979 deadline felt a certainty.

No longer could states (or the federal government, for that matter) implement laws that denied a woman the right to own property, start a business, or obtain a loan on her own, or stop her from holding certain types of jobs, demanding the same pay as male colleagues, or continuing to work after marrying or when pregnant. No longer would women have to pick off discriminatory practices one at a time, lawsuit by endless lawsuit. No longer would they have to hold their collective breath every four years that some anti-women administration or Congress could be elected and start rescinding their rights. The Constitution would protect them.

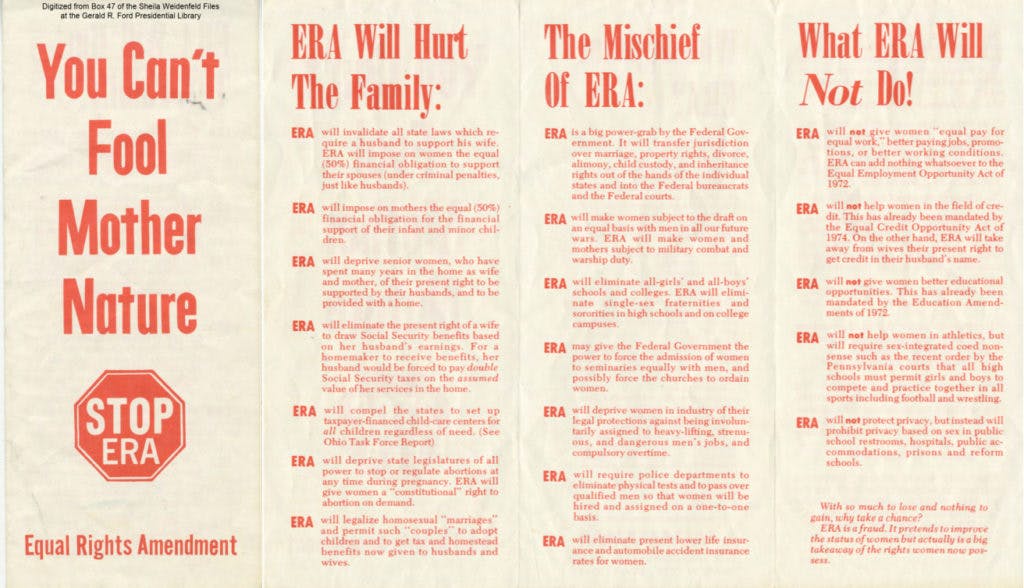

But that was before the backlash—led by Phyllis Schlafly and a coalition of conservatives, many of them upper class, suburban housewives. They flooded state houses wearing STOP ERA pins (Stop-Taking-Our-Privileges). Armed with home-baked bread and valentines, they begged legislators to “save motherhood.”

Schlafly had convinced them the ERA would destroy the American family. That women would be required to produce 50 percent of a household’s income and denied the choice of being stay-at-home mothers, thereby ruining children’s lives. STOP ERA activists also insisted the amendment meant women would be drafted for combat duty, would have to share jail cells or public toilets with men, and that husbands would no longer be required to financially support them or their children either during marriage or in the case of divorce.

Schlafly’s arguments turned the varying hopes and dreams of women into a bitter culture war about gender roles and “family values,” fueling the rise of the “moral majority” and the religious right’s political clout. When that anti-ERA, anti-abortion coalition elected Ronald Reagan president, he became the first since the ERA’s passage to oppose it—even though 83 percent of polled Americans believed the amendment should become law.

When the ratification deadline came (extended to June 30th, 1982), the tally of required states fell short. By three states.

Since then, fewer and fewer Americans even know what the ERA is. Nonetheless, devoted feminists and civil liberties experts have continued fighting for it.

And technically, they won.

Nevada ratified the ERA in 2017, Illinois in 2018, and in 2020, Virginia became the 38th and final state needed. The requirements to enshrine the ERA in our Constitution had been met—approval by 2/3rds of both chambers of Congress and ratification by 3/4ths of states.

In response to Virginia’s 2020 ratification, the House voted to remove the 1982 deadline, clearing the way for its codification (by the way, the ERA is one of the few amendments to have a deadline imposed on it). But recognition of the ERA was blocked by the Trump Administration and Senate Republicans and has been stalled in Congress ever since.

Today:

Recognizing that the ERA would be a seawall against the continuing pay inequities women face and the growing denial of their reproductive rights post-Dobbs, Congresswomen Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Cori Bush (D-Mo.) created the Congressional Caucus for the Equal Rights Amendment. On the Senate side, Kirsten Gillibrand (D- NY), Ben Cardin (D-Md), and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) have pushed resolutions in the Senate to affirm the validity of the ERA as constitutional law.

As our Constitution’s 28th amendment, the ERA will guarantee federal protection of women’s reproductive freedoms— making moot the Dobbs decision that upended 50 years of rights provided by Roe v Wade—since it would become unconstitutional for government—federal or state—to deny access to medical care based on gender.

The 1973 Roe decision was based on interpreting the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause as implying a right to privacy. Senator Gillibrand explains: “Dobbs ruled that woman-of-reproductive-years do not have a right to privacy—which red states have then implemented to say they don't have the right to travel across state lines to gain access to health care. That women-of-reproductive-years don't have the right to have private conversations on their Facebook pages with their mother about seeking abortion services. That women don't have the right to privacy to receive medicine in the mail. Imagine how men would feel if told the same thing?

“With the ERA, Dobbs would no longer count because it is applying a standard to women based only on their gender.”

The Columbia Law School’s Center for Gender & Sexual Law agree with Senator Gillibrand that the ERA's explicit guaranteed equity would protect a woman's reproductive rights and access to abortion—as do the ALA and 23 states attorneys.

In 2007, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in her dissenting opinion on Gonzales v. Carhart that a stereotyped, gendered notion of citizenship in which women were “regarded as the center of home and family life, with attendant special responsibilities that precluded full and independent legal status under the constitution” denied equal citizenship. She added, “Those views are no longer consistent with our understanding of the family, the individual, or the constitution” and full citizenship in the workplace as well as home “is intimately connected to a person's ability to control their reproductive lives.”

In the last weeks of December 2024, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), and the House ERA Coalition called on President Biden—before he left office—to order the National Archivist to certify and publish the ERA. How would that make the ERA law? With Virginia’s 2020 ratification, the ERA met the standards required by the U. S. Constitution for adding amendments. But there’s one final step for an amendment to become law—the National Archivist must officially re-publish the Constitution including it. The Senator insisted the President could do so since a ratification deadline is nowhere required in the Constitution. Therefore, she argued, the deadline should be ignored.

In January 2025, President Biden pronounced: “The Equal Rights Amendment is the law of the land. . . In keeping with my oath and duty to Constitution and country, I affirm what I believe and what three-fourths of the states have ratified: the 28th Amendment is the law of the land, guaranteeing all Americans equal rights and protections under the law regardless of their sex...It is long past time to recognize the will of the American people.”

But the National Archives reiterated its previous position under the first Trump administration and refused to publish, saying “the underlying legal and procedural issues have not changed.”

When one knows how universal the acceptance and excitement over the ERA was when Congress almost unanimously passed it and how 30 out of 50 states ratified within one year—it’s beyond baffling how it could have unraveled. Even arch-conservative Strom Thurmond (R, SC) supported it, saying in 1974: “This amendment would not downgrade the roles of women as housewives and mothers. It would confirm and uphold a woman's right to choose her place in society. I want my daughter, Nancy, to grow up with a full guarantee of every right and opportunity that our great country provides for all its citizens.”

A cautionary tale, perhaps, of truth, lies, and questions in between—and the danger of not confronting pebbles of fearmongering, hate labels, and disinformation before they turn into an avalanche.

Right before the historic National Women’s Conference of 1977, knowing they had a hard battle ahead of them against anti-ERA and anti-choice forces, Jill Ruckelshaus—the influential moderate Republican feminist, who today would probably be dismissed as a “republican-in-name-only (RINO)"— spoke to a NWPC gathering. As a devoted leader of the NWPC and its bipartisan quest to groom women to run for office at all levels, Ruckelshaus had long and eloquently urged what feminists have now learned the hard way post-Dobbs: that tweets, impassioned Oscar speeches, and cultural representation are great, but do not have the same power as legislative seats and votes.

Her stirring words at that 1977 meeting were bittersweet but determined, and hauntingly apply today: “Sisters, you were all here because you are smart. You are committed to an idea that is much larger than ourselves or the length of our lifetimes. You want to elect women to public office because we want to gain some control over the issues that affect our lives.

“We want the women of America to understand what it is to be raised female where we have met the government and it is not us. Somebody is making laws in this country that affects our legal rights, even our basic right to control our own bodies. And there are not enough of us among those somebodies.

“We’ve learned that we have to win our fight, then win it again four years later, and four years after that...We are in for a very, very long haul. I am asking for everything you have to give...your youth, your sleep, your patience, your sense of humor...your pride in being a woman and all your dreams you've ever had for your daughters, and nieces, and granddaughters.”

You can read more about the ERA in a Ms. Magazine’s series devoted to the amendment.

And here: https://www.alicepaul.org/equal-rights-amendment-2/

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/equal-rights-amendment-explained

https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/

Congress.gov: frequently asked questions about the ERA

Documentaries about the ERA:

For a quick summary and a lesson plan: PBS’ American Experience: Women’s Suffrage to the ERA, a Century-long Push for Equality.

PBS: Not Done: Women Remaking America

PBS: 9 to 5: the Story of a Movement

Netflix: Feminists: What Were They Thinking

Equal Means Equal produced by Kamala Lopez plus a general directory of resources for women's rights

HBO/Max: Gloria: in Her Own Words

NY Historical Society: https://www.nyhistory.org/womens-history

A study guide: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/equal-rights-amendment-97-year-struggle#lesson-plans