Laura's Blog

What Would Publishing the ERA do?

December 29, 2024

In the last weeks of December, there’s been a flurry of reports about Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), and the House ERA Coalition calling on President Biden—before he leaves office—to order the national archivist to certify and publish the ERA.

Please see my more complete portrait of the ERA, the women who rallied for it and those who fought against it, on the landing page for TRUTH, LIES, AND THE QUESTIONS IN BETWEEN. But in short, here’s the reason Gillibrand and others are in overdrive right now trying to get this done before Trump’s second presidency: if it becomes law as our constitution’s 28th amendment, the ERA guarantees federal protection of women’s reproductive freedoms, making moot the Dobbs decision that upended 50 years of rights provided by the Roe v Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973. The ERA would make it unconstitutional for government—federal or state—to deny access to medical care based on gender.

Why is a clerical technicality either the hold-up or answer to women’s hopes for equality? The ERA has met the two standards required by the U. S. Constitution for adding amendments: a 2/3rds affirmative vote in Congress (accomplished in 1972) and ratification by 3/4ths of the states (reached in 2020 when—in reaction to Trump’s first presidency and sexist rhetoric and policies—Virginia became the 38th state to ratify). But there’s one final step for an amendment to be law—the federal government’s archivist must officially re-publish the constitution including it. And following Virginia’s assent, the Trump administration ordered the archivist to NOT publish, arguing the imposed final deadline for ratification (1982) had long passed.

Let’s back-up for a minute. The ERA is a simple statement: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Seems like a no-brainer in a democracy promising justice for all—equality of opportunity, pay, individual freedoms, and choice. And yet, somehow, codifying the Equal Rights Amendment has proved anything but simple.

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, after decades of it languishing in congressional committee, the ERA was revived by second wave feminists—Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisholm, and Bella Abzug to name a few of the best-known—leading a women’s liberation movement, a cultural awakening that turned America’s world upside down.

Using an obscure procedural tactic, Congresswoman Martha Griffiths (D-MI)—one of only twelve females among the 435 House members in 1972—managed to convince and cajole the needed number of congressmen to sign a discharge petition, helped by Republican leader Gerald Ford.

That passage is a sterling and stunning (especially given today’s bitter divides) example of bipartisanship. The House adopted the ERA with a resounding 354 yeas to a mere 24 nays, and in March 1972, the all-male Senate passed it 84 to 8. Nixon supported it too!

Within minutes of that Senate vote, Hawaii ratified it, followed within 48 hours by Delaware, New Hampshire, Iowa, and Idaho. By the end of the year, 22 states had voted yes. Three months later, in March 1973, the ERA had 30 out of the required 38 states.

Feminists were giddy with hope that final ratification would only take two of the allotted seven years. Finally, American women would have universal protection of rights rather than having to undo discrimination state-by-state, one expensive, drawn-out lawsuit at a time. No anti-women White House or Congress could start rescinding their rights. The constitution would protect them.

That was before Phyllis Schlafly.

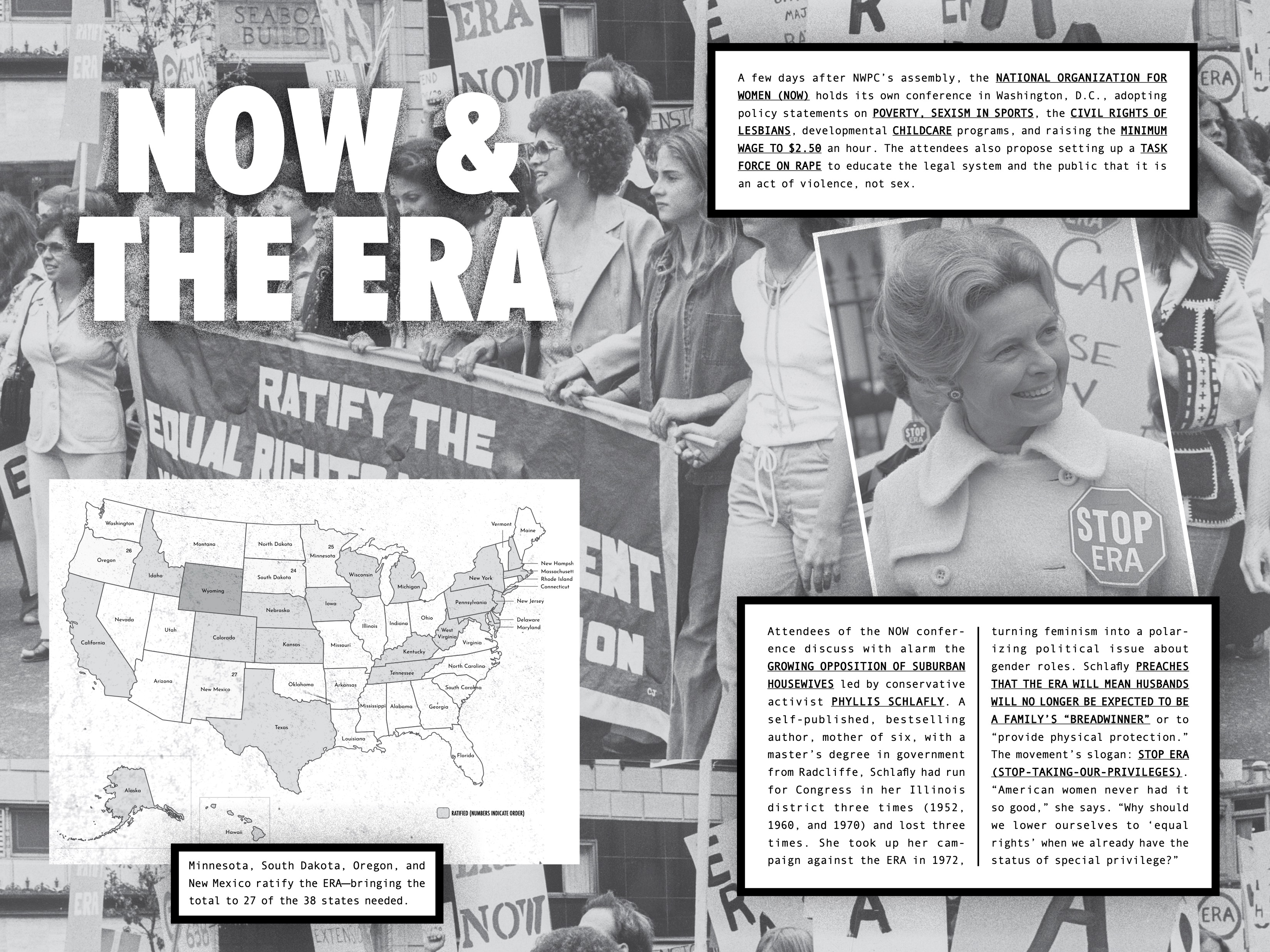

A conservative, self-published, and best-selling author, mother of six, with a master's degree in government from Radcliffe, Schlafly had run for Congress and lost three times (1952, ’60, ’70). In 1972, she set her political sights and ambitions on undoing the ERA, turning feminism into a bitter political debate about gender roles. She played on housewives’ fears, claiming the ERA meant their husbands would no longer be expected to financially support them or their children, that men could divorce wives without having to pay any alimony, and—even if happily married—wives would be required by constitutional law to produce 50 percent of a family’s income, thereby taking away their choice to be stay-at-home moms.

Schlafly said, “American women never had it so good. Why should we lower ourselves to equal rights when we already have the status of special privilege?” Her crusade’s slogan became STOP ERA (Stop-Taking-Our-Privileges.) She and her followers flooded state houses, armed with home-baked bread and cards saying: “To the breadwinners, from the bread-bakers. Please protect motherhood.”

Suddenly ratifications slowed and stopped, ultimately coming up three states short by the 1982 deadline. By the way, most amendments have not had a time-limit imposed on them.

There’s an eerie similarity between today and 1973 that makes this 11th-hour push for the ERA feel exceedingly urgent. A chilling echo in the rhetoric of Moms for Liberty, TradWives, and Project 2025 of the original STOP ERA backlash and accusation that women having agency somehow destroys American families; in J. D. Vance’s snipe against miserable “childless cat ladies” and Schlafly’s damnation of “sharp-tongued whining unmarried women, sowing seeds of discontent."

The Supreme Court’s (7-2) Roe decision in 1973 hinged on interpreting the 14th Amendment’s due process clause to imply the right to privacy—making reproductive choice an individual, private right. This was a gutsy argument made by 26-year-old attorney, Sarah Weddington, at a time when only four percent of American lawyers were female, and only a year after single women were allowed by law to purchase the pill.

In an interview with the New York Times Daily podcast, Senator Gillibrand explained the connection between the Dobbs decision and the ERA: “Dobbs ruled that woman-of-reproductive-years do not have a right to privacy, which red states have then implemented to say they don't have the right to travel across state lines to gain access to health care. That women-of-reproductive-years don't have the right to have private conversations on their Facebook pages with their mother about seeking abortion services. That women don't have the right to privacy to receive medicine in the mail. Imagine how men would feel if told the same thing? With the ERA, Dobbs would no longer count because it is applying a standard to women based only on their gender.”

The Senator also insists a ratification deadline is nowhere required in the constitution, and therefore should be ignored—especially since most amendments have not been subjected to one.

In my epilogue to TRUTH, LIES, I explained that according to Columbia Law School’s Center for Gender & Sexual Law, the ERA's explicit guaranteed equity—regardless of sex or gender—would also protect a woman's reproductive rights and access to abortion. Clearly the center’s experts agree with Gillibrand’s legal analysis—as do the ALA and 23 states attorneys.

In 2007, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in her dissenting opinion on Gonzales v. Carhart that a stereotyped, gendered notion of citizenship in which women were “regarded as the center of home and family life, with attendant special responsibilities that precluded full and independent legal status under the constitution” denied equal citizenship. She added, “Those views are no longer consistent with our understanding of the family, the individual, or the constitution” and full citizenship in the workplace as well as home “is intimately connected to a person's ability to control their reproductive lives.”

Gillibrand concedes that if President Biden does order the amendment published before he leaves the White House, Trump will inevitably challenge it in court. But she (and many feminist activists) welcome that fight—essentially daring Republicans to wage a very public battle to strip women of what then would be constitutionally-mandated rights that even arch-conservative Strom Thurmond (R, SC) supported, saying in 1974: “This amendment would not downgrade the roles of women as housewives and mothers. It would confirm and uphold a woman's right to choose her place in society. I want my daughter, Nancy, to grow up with a full guarantee of every right and opportunity that our great country provides for all its citizens.”

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts