[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Walls ]

Historical Facts & Learning Resources

Walls

One of the biggest lessons I learned as a magazine journalist that I’ve brought to writing novels is to look for “holes in coverage”—topics that haven’t yet been fully explored.

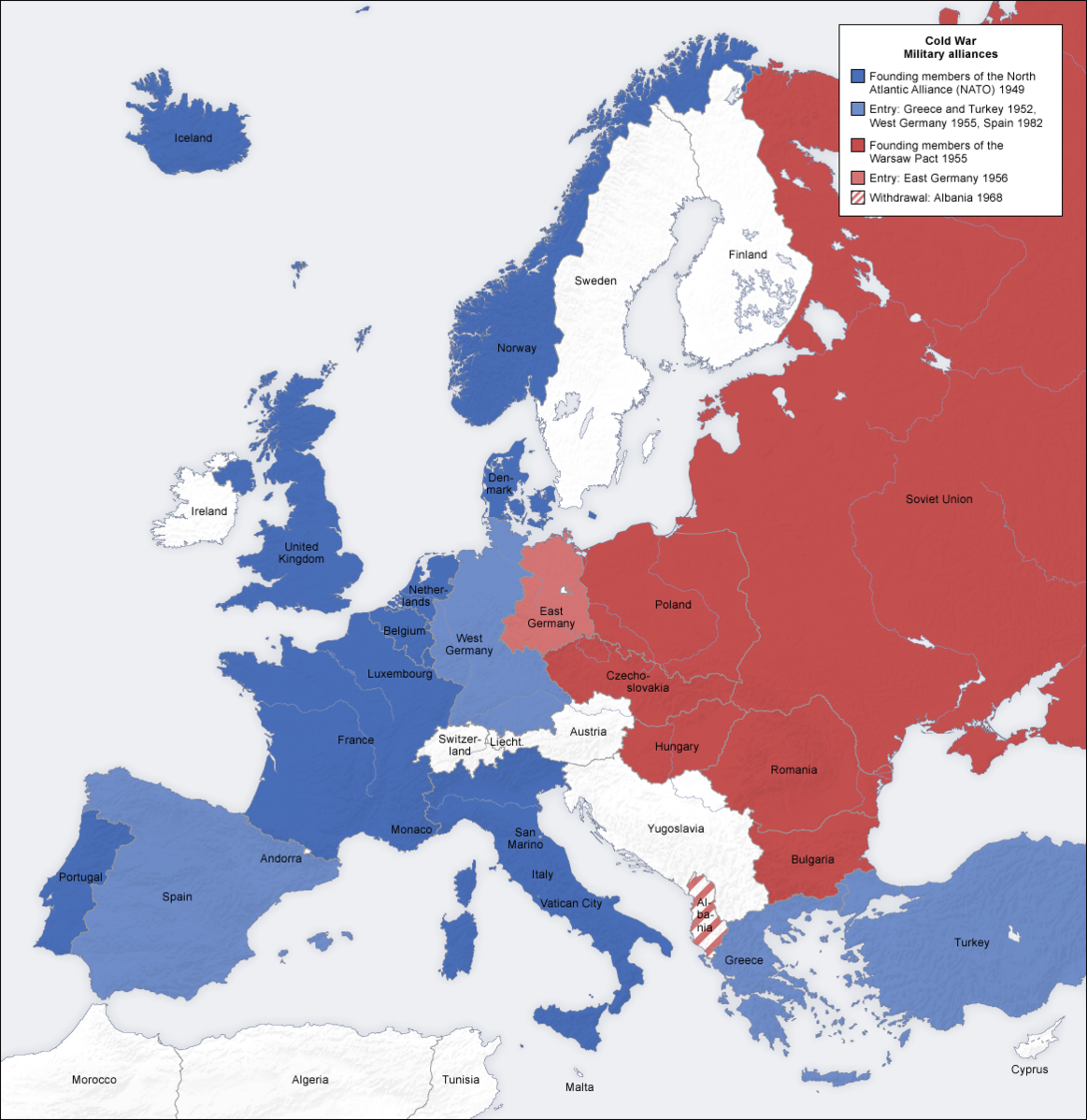

When some politicians recently questioned the relevance of NATO, I wondered if people remembered the frightening reasons NATO was formed: Russia’s brutal annexation of Eastern Europe after WWII to create a Soviet Bloc of puppet states, followed by the Berlin Wall. Beyond knowing that the Alliance and the Wall existed, teens and Gen Zers I asked knew little else. I found several moving novels about life behind the Wall, but nothing about the tense lead up to its raising or what it was like being an American military kid stationed 100 miles behind the Iron Curtain, where dads could be mobilized at any moment against a nuclear-armed foe, outnumbering them 10 to 1.

A definite hole in coverage. And what could be a more dramatic, show-rather-than-tell story humanizing the Cold War standoff between Western democracies and totalitarian communist regimes?

Here is a BRIEF synopsis of what lead to the factual powder keg circumstances and setting of WALLS (for more, see the resource links provided below):

The Division of Germany

During WWII, the Soviet-American alliance had been a wary but necessary one to defeat Hitler. American, British, and French soldiers landed on Normandy beaches on D-Day and battled their way inland and then east across France. The Russians came from the opposite direction, marching through Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. The Nazis were caught and attacked from two sides.

However, when Russia’s Red Army liberated an Eastern European country from Hitler’s troops, the Soviets took it over. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine were simply absorbed. Others were turned into a band of “satellite” Soviet Bloc nations, including Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the eastern half of Germany. Any resistance was quickly put down by Russian troops and tanks. Britain’s Winston Churchill famously called this disturbing and enormous Soviet land-grab and ruthless rule an “Iron Curtain” of oppression.

After the Nazi surrender, the Allies occupied Germany to restore order and purge it of Nazism. The United States, Great Britain, and France oversaw Germany’s Western zones to establish a new democracy. Russia retained the country’s Eastern half, instigating a communist puppet state, which was ironically renamed the German Democratic Republic.

West/East Berlin

Because it had been Hitler’s capital, Berlin was also divided similarly into four sectors (American, French, and British vs. Soviet) despite being marooned deep inside Russian-held East Germany. The city quickly became a poignant and dangerous microcosm of West versus East Germany, the toe-to-toe epicenter of the Cold War standoff. Within Berlin itself, up until August 1961, residents could still cross its internal sectors—from communist to democratic and back. As such, Berlin became an escape hatch to freedom. If East Germans could evade the GDR’s secret police and paid informers, cross the barrier and death strip encircling the city, and make it into Berlin, they might then be able to slip into the city’s American sector to beg political asylum. Hundreds tried every week, fueling the friction between the U.S. and Soviet Russia.

Image Source: The United States Air Force

The Berlin Blockade

Russia did everything it could to dislodge the Americans. Isolated so far inside Soviet-controlled East Germany, our Berlin troops relied on supplies brought in by air or along the GDR-operated rail line running 110 miles through the communist zone—if the Russians kept the tracks open. In the spring of 1948, incensed that West Germany and West Berlin’s economies were booming under American support, the Soviets ordered a blockade, determined to starve Western troops into evacuating and two million West Berliners into submitting to Russian rule.

The U.S. responded with its daring “Operation Vittles,” airlifting fuel, medicine, and foods into West Berlin. For eleven grueling months, our Air Force pilots landed cargo planes every 30 to 60 seconds at Tempelhof Airport, no matter how perilous the weather. Hungry Berliners waited beside the runways. Seeing children below, American pilots began tossing out parachute bags of sweets for them. The “candy bombers” became much-beloved legends among young West Berliners.

Finally, Russia relented and reopened roads, canals, and trains to West Berlin in May 1949.

Formation of NATO

In answer to Russia’s blockade of Berlin and its iron-fisted control of Eastern Europe, twelve Western democracies created NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), pledging to support one another against Russia’s territorial aggression and attacks on democracy. Those original members included: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Greece and Turkey were added in 1952, West Germany in 1955.

Meanwhile, Soviet Russia plundered East Germany for resources and food, leaving East Germans poor and hungry. As a result, the differences between life in East and West Berlin became stark (see more in my East Berlin section). The GDR also seized family farms, broke them apart, and gave lands to loyal Communist Party members to form agricultural collectives, forcing owners to till land that no longer belonged to them. They also enforced backbreaking production quotas on laborers.

Image Source: German Federal Archive

Crushing the Workers’ Protest

In June 1953, when the GDR demanded another ten percent increase in worker productivity without any raise in pay, East German workers finally had enough and took to the streets in protest. They asked for decent wages, more humane and realistic quotas, and the right to vote. The demonstrations started in East Berlin and spread to 700 other cities and villages.

Within days, Russian tanks rolled into the communist sector of Berlin to crush the uprising. With nothing but rocks to hurl, the protesters were quickly overcome. Perhaps as many as 300 died in the fighting, and 4,270 were imprisoned.

Attempts to escape to the West skyrocketed.

1960-1961

During the year of my novel, the Red Army remained entrenched in East Germany, 400,000-strong, against which a mere 11,000 American, British, and French soldiers stood post in West Berlin, protecting the citizens of that teeny democratic sector.

JFK said of the city: “Berlin is. . . a showcase of liberty. . .an island of freedom in a Communist sea. . . a beacon of hope behind the Iron Curtain.”

Countered Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev: “Berlin is the testicle of the West. When I want the West to scream, I squeeze on Berlin.”

This was the world of my characters. To capture the experience of both sides of that tense time, I created two fictional cousins—Drew, an American Army kid stationed in West Berlin, and his distant cousin, Matthias, an East German raised in the Soviet sector. At the novel’s opening, people could still cross back and forth within the city’s free and Soviet sectors. The boys’ mothers want them to be friends despite all the obstacles and the dangerous scrutiny it brings both teenagers. Soon the cousins are embroiled in the spy thriller-worthy intrigues that truly swirled around Berlin as the Cold War’s epicenter (see the novel’s afterward for specifics).

The question of what it would take for that East Berlin youth—inculcated in communist dogma, bombarded with Anti-American propaganda, spied on by Spitzel (paid neighborhood informants) and ardent Freie Deutsche Jugend (“Free German Youth”)—to trust a Westerner, and vice versa, felt a poignant and powerful question to explore.

I researched and built Drew by interviewing a number of “Berlin Brats,” whose fathers were stationed in West Berlin when the Wall went up. They were incredibly generous with their memories and time. Drew’s experiences and outlook—the menacing overtures and harassment of Allied personnel and their families by the KGB and their East German minions; the unnerving aura of being 100 miles behind the Soviets’ “Iron Curtain” and surrounded by 400,000 Russian troops; the eerie anxiety of traveling in a duty-train through the communist zone to play other high school sports teams; and living in a landscape still dotted with reminders of the Nazi idealization of “the master race”—are all haunting details these gentlemen shared.

American military kids faced far more dangers than I imagined. If their fathers were intelligence officers, for instance, and they got too close to the sector border, they were vulnerable to Stasi secret police picking them up to hold overnight as a way of threatening, or trying to turn, those parents. “Berlin Brats” had to be careful if they volunteered at the Marienfelde refugee camp as well. Stasi double agents posed as refugees to eavesdrop on conversations to gain useful information about American personnel or relocated Germans for coercive blackmail.

In short, it was a place where a mistake or a typical lighthearted teenage prank could potentially spark an international incident or undo a parent’s military career. No joke, as those “Berlin Brats” would say with a characteristic touch of bravado.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

edsitement.neh.gov/

edsitement.neh.gov/

The Cold War, the Soviet Bloc, division of Germany:

A documentary by DW News, Germany’s Public International Broadcasting: dw.com/en/east-germany-a-failed-experiment-in-dictatorship/a-50717157

britannica.com/place/Germany/The-era-of-partition

history.com/topics/cold-war/cold-war-history

khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/postwar-era/v/origins-of-the-cold-war

pbslearningmedia.org/resource/pres10.socst.ush.now.coldwar/the-beginning-of-the-cold-war/

pbs.org/video/american-experience-cold-war-roadshow-chapter-1/

The Iron Curtain:

winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1946-1963-elder-statesman/the-sinews-of-peace/

nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/cold-war-on-file/iron-curtain-speech/

The Berlin Blockade and the leadup to NATO:

history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-blockade

history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-airlift

history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/berlin-airlift

khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/postwar-era/a/start-of-the-cold-war-part-3

NATO:

nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_139339.htm

defense.gov/Explore/Features/story/Article/1650880/what-does-nato-do/

history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/nato

britannica.com/topic/North-Atlantic-Treaty-Organization

For more on the Berlin Wall, see section The Night the Wall Went Up.