[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to A Troubled Peace ]

How Much Is True?

A Troubled Peace

(I need to tell readers right now what a large impact your emails and our school visits together had on this sequel. When I learned that even boys seemed so worried about whether Patsy and Henry married, I started testing out a beginning to the sequel when I spoke to schools where students had already read the novel. Their gasp and what?!!! reaction told me I had the correct opening)!

While the plot is made up, the backdrop of this novel is factual. As always, my research told me what to write, where to take my characters, what challenges to throw at them. It was as if Pierre and the real life people I read about took my hand and led me. It was an amazing journey, full of revelations. Once again, I was awestruck by the strength of the human spirit, by the good and the hope that can stubbornly exist amid inhuman cruelty and selfishness.

World War II lasted six years and embroiled 57 nations. It's thought that 55 million people perished, most of them civilians. Across Europe, 13 million children were orphaned. In France alone, 211,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen died, but so, too, did 600,000 civilians. These children, women, and men died in battle bombardments, landmines left by the Nazis, massacres in retaliation for Resistance activity, deportation, and, tragically, in Allied bombings designed to liberate them.

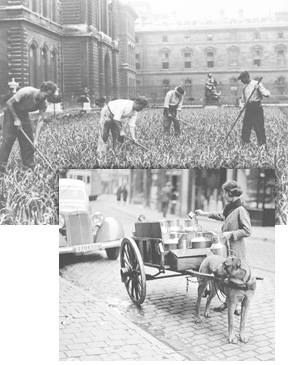

By V-E Day, May 8, 1945, most of France's bridges, railways, trains, and canals had been blown up—by the French Resistance to slow German reinforcements after D-Day or by the retreating Nazis to impede the Allies' pursuit of them. As the Allied armies chased the Nazis eastward from the Normandy beaches, homes, churches, hospitals, and town halls were blasted to ruins in bloody village-by-village fighting. Five million French were left homeless. It became nearly impossible to transport what little food was being produced, what coal there was to generate electricity, what supplies the Allies dropped from planes by the tons. Starvation ravaged France.

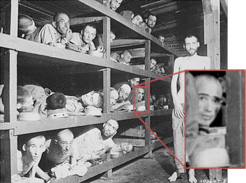

I wept at the memoirs that described the return of what the French called "the absents"—the 1.5 million P.O.W.s and the thousands upon thousands deported as slave labor and to concentration camps. As the Allies stumbled onto the hellish death camps—Buchenwald, Auschwitz, Ravensbruch—they shipped the survivors home as quickly as they could. Broken, emaciated, and ill, thousands arrived in trains to Paris each day in the spring of 1945. If no one met them at the station, they were taken to a refugee center run in an elegant art deco hotel, the Lutetia. Why there? The hotel had been occupied by the Abwehr, the Nazi counter-intelligence agency and when they fled Paris and the oncoming Allies they left it well stocked with food, wine, medicine, and linens.

So once again, Henry's story is not just his, it is also about the real life people who managed to survive and find their way out of the rubble and brutality of war.

Many of the people Henry meets truly lived, such as Madame Zlatin, who managed the Lutetia's center. She hid 44 Jewish children from the Nazis during the war and tirelessly worked afterward to help lost children find their parents. The Vercors man I call le patron is based on the real Resistance leader in that area, who arranged daring raids such as liberating 52 Senegalese soldiers from a Nazi garrison with only a handful of men. There are others—but you need to read the book first and then check my afterword for more details. I don't want to give away too much!

As for the character Henry, his personality—his resilience and innate kindness—remain reflective of my father's, just as in Under a War-torn Sky. In A Troubled Peace, Henry also suffers what we now know as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Not many WWII veterans admitted to readjustment problems, nightmares, or flashbacks (then simply called battle-fatigue or being flak-happy), but few combat veterans return completely untouched emotionally—even those who win special commendations for their courage under fire. When I was very young, my father cautioned me to never wake him while he slept by touching his arm. "Always call my name first," he said. When I asked why, he answered that there had been a time he had to be on alert, even when asleep, and he was afraid he might lash out with a self-preservation reflex and hurt me. That was more than fifteen years after the war ended.

As you read A Troubled Peace and look at some the links I have included here, I hope you are inspired and energized by the people who had the resolve and the raw courage to bring us out of the darkness of WWII. Remember what Anne Frank could express, so remarkably, as she hid from the Nazis in tiny, closed rooms: "In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart."

Let us have faith in mankind’s potential, then, and work for an untroubled peace among all nations. One Auschwitz survivor said, "The road to Auschwitz was built by hate, but paved with indifference." Buchenwald survivor and author of Night, Elie Wiesel adds, "I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented...

"Peace is our gift to each other."

Author essay about her father and his influence on the personality of Henry Forester and the themes of A Troubled Peace.

Frankly, I was completely unprepared for what I discovered about the level of chaos left in the wake of war ---the destruction, the hunger, the bitter vigilant-style retributions, the political upheaval that raged after liberation.