[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Suspect Red ]

Richard's Reading List

Suspect Red

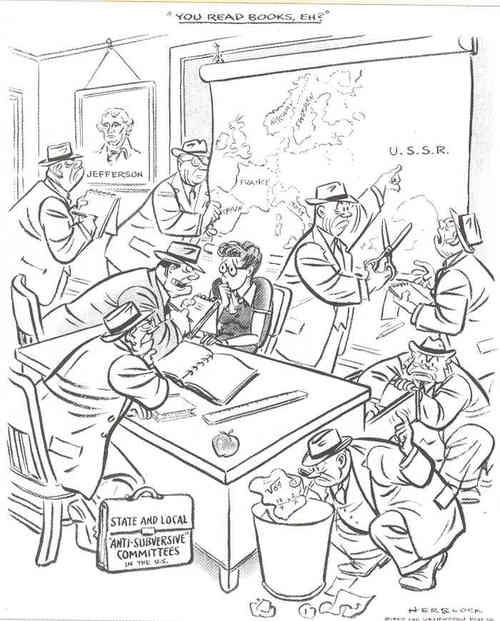

Richard could have gotten into serious trouble, scrutinized as “subversive," "Red," or “pinko,” for all the books he reads during the course of my novel (except Philbrick’s I Led 3 Lives and Casino Royale). That would include several now considered part of English Literature canon: The Catcher in the Rye, Fahrenheit 451, Invisible Man, and Go Tell It on the Mountain (each published during my novel’s timeframe), as well as John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony or Of Mice and Men, and Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. Richard and Vlad also read Call of the Wild and The Maltese Falcon, both adapted into much-loved movies.

And, of course, Robin Hood—which an Indiana textbook commissioner urged schools across the nation to ban in 1953 because it advocated “robbing the rich” and “smearing law and order.”

Just as McCarthy’s arrogant attack of a decorated WWII general—who was good friends with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of Allied Forces during the war—was the senator’s fatal mistake in terms of public opinion, so was the censors targeting the Merry Men. Students at Indiana University collected six bags of chicken feathers from local farms, dyed them green to match Robin’s forest camouflage, and passed them out in protest to their fellow IU students. Despite public rebuke and FBI harassment, the movement spread to university campuses like Harvard and UCLA. It was the beginning of college student activism that would prove such a powerful force for civil rights and anti-Vietnam protests.

For more on the Green Feather Movement:

https://zinnedproject.org/materials/the-green-feather-movement/

http://www.teachingforchange.org/green-feather-movement

https://lmelliott.com/

On helping improve teen media literacy:

http://www.ala.org/yalsa/

Fahrenheit 451

Published in 1953 at the height of book-censorship in this country, Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel presents a future world in which books are banned and burned by “firemen” to stop their spreading ideas that could undo the repressive government.

The Catcher in the Rye

Published initially for adults, J. D. Salinger’s story of Holden Caulfield quickly became a kind of battle-cry book for teenagers because of the authenticity of its first-person 16-year-old narrator, his angst, alienation, and often poetic sense of complete bafflement with adults and status-quo, “acceptable” society.

Invisible Man

The first novel by an unknown African-American writer, Invisible Man won the National Book Award for fiction in 1953. An unflinching portrait of growing up in the South’s black community, New York’s Harlem, and the horrors of surviving white attitudes and racism. A Harvard professor drew an interesting parallel to today in terms of this novel’s continuing relevance: http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/ralph-ellisons-invisible-man-as-a-parable-of-our-time

Go Tell It on the Mountain

A semi-autobiographical story of a teenage son of a Harlem Pentecostal Church preacher. Go Tell It on the Mountain has remained on countless 100 Best lists of 20th century literature since its appearance in 1953.

Of Mice and Men

The heartbreaking story of two migrant ranch workers during the Depression. It and Grapes of Wrath were routinely banned or burned as being “subversive,” i.e. spreading proletariat ideals and criticizing American capitalism and society by portraying the plight of laborers. Finally, in 1962, Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception."

Remember 1962 is the height of the Cold War and our terrifying standoff with the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Steinbeck aptly concludes by saying: “Having taken Godlike power, we must seek in ourselves for the responsibility and the wisdom we once prayed some deity might have. Man himself has become our greatest hazard and our only hope.”

Casino Royale

The first in the James Bond series.

The Call of the Wild

A classic adventure, boy-and-his-dog story set in Canada during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush. Much discussed then but almost forgotten today, is the fact Jack London was part of a radical literary group in San Francisco that advocated for workers, unions, and socialist programs.

The Crucible

A play about the Salem witch trials in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, The Crucible opened in 1953. Arthur Miller’s drama was also a metaphor for McCarthyism’s mob mentality and persecution of innocent people because of their association with others suspected of wrong-doing or heretical thinking (political in the 1950s, religious in the 1690s.) The parallels were recognizable and unnerving enough to Red-Hunters that Miller was denied a travel visa to Belgium to see a premiere of his own work in that country ”under regulations denying passports to persons believed to be supporting the Communist movement, whether or not they are members of the Communist party.”

The Maltese Falcon

One of Dashiell Hammett’s most popular LA noir novels, starring private detective Sam Spade. The Maltese Falcon also became a favorite Humphrey Bogart film classic. Both Hammett and Bogart were harmed by McCarthyism.

Hammett served in WWI, driving ambulances, and then during the 1930s became politically active in the pro-union movement, joining the American communist party when it was still simply a progressive labor party, and becoming vice-chair of the Civil Rights Congress. After WWII and the USSR’s repression of satellite nations, such activism during the Depression was labeled Red. Hammet spent six months in prison on contempt charges for refusing to “name names” or to testify against friends accused of conspiracy. After his release, his Sam Spade radio series was cancelled and the IRS prosecuted him for failure to pay back taxes. McCarthy decried his books as subversive and called for their banning.

In 1947, the Hollywood Ten were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). A number of well-known actors such as Bogart formed the Committee for the First Amendment, purchased space in newspapers like the New York Times to run a petition supporting the accused screenwriters, and flew to Washington to witness the Congressional hearings.

Many Hollywood film workers who signed that petition were later questioned by HUAC. When it became clear that a few of the screenwriters were indeed members of the American Communist party, Bogart—a WWII veteran and New Deal liberal Democrat horrified by Stalin’s growing power and human rights violations—was incensed. He wrote an article stating he had been duped and he was no communist. Fellow liberals publicly lashed out against Bogart, accusing him of selling out to save his career.

For more on the Hollywood Ten see:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hollywood-Ten

Excerpt from Chapter One of SUSPECT RED:

School was out, summer was on, and Richard had a stack of books he planned to read. Stuff that would obliterate all the crumb-bum melodrama of 8th grade—the cliques that froze out a kid who liked to read and couldn’t roller-skate. The girls who went steady with dopes who greased their hair into duck-butts. Girls who turned their pretty noses up at a guy who talked about the Holy Grail or Sherlock Holmes or Sam Spade.

In September, Richard would wade back into that donkey manure. Maybe high school would be different. But this summer? Richard was going to escape. He’d travel universes created by his books—no moldy old mush dictated by school wardens. Good stuff—heroes, spy intrigues, quests, underdogs winning the day, private detectives cracking crime cases, and a couple of dames in distress. He’d even squirreled away a copy of that novel all the parents hated, Catcher in the Rye.

He was reading Salinger’s novel in chunks, under his sheets at midnight with a flashlight, knowing it dangerous stuff. Last night, the 16-year-old narrator—Holden Caulfield—ran away from boarding school, after getting his nose busted by a jerk in his dorm. Richard pulled out the pocket-sized spiral notebook in which he jotted things down that he really liked. He re-read some Holden truths he’d copied out.

“You can always tell a moron. They never want to discuss anything intelligent…”

Richard nodded. Exactly.

“What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.”

Right again. Sometimes books could be better friends than kids. No kidding.

Richard ran his hand along the forest green cover of the novel he’d brought to the kitchen table with him. He’d love to talk to the guy who wrote it. Robin Hood. Classic stuff. He’d read it before, but the story never got old. How could it? A former knight, now outlaw, hanging out with forest desperados, taking down a bully, and winning the prettiest maiden in the land.

Everyone was asleep. No interruptions. Richard opened the book. Instantly, he no longer sat in a tidy, perfectly symmetrical brick colonial in northwest Washington D.C.. Instead, he stalked the gloam of Sherwood Forest in the age of the Crusades. He came upon an ambush.

“It was a wild spot; and only the notes of the birds and the rush of falling water disturbed it. But ere they proceeded a quarter of a mile up the stream a sudden bend brought them the harsh noise of desperate fighting.

"Richard!"

Richard flinched, Sherwood Forest evaporated.

His mother stood in the doorway in a hot pink bathrobe, her blonde hair a crown of neatly bobby-pinned swirls. “What in the world are you doing up this early, honey?” Abigail asked. “It’s summer vacation.”

“Reading.” Richard answered without looking up, trying to recapture the forest battle.

Abigail gasped. “You can’t read that!” She slammed the book shut on Richard’s fingers and pulled it off the table.

“What the heck, Mom!” He tried to reach for it, but she turned, cradling the book in her arms.

“What if Mr. Hoover knew you’re reading this?”

Richard’s dad was an FBI agent, a G-man. Mr. Hoover—the agency’s director, lived on the next street. Sometimes Hoover had his driver stop in front of their house and his dad rode into work with him or was given instructions for some case or something. His dad always got the weirdest look on his face when that happened.

His mom was always so all-fired worried about impressing Hoover. It was like how Richard felt at school with the principal. He knew Abigail’s concern came from love for his dad. But Richard couldn’t help it. Her being a worrywart annoyed the heck out of him.

“Why would Mr. Hoover care about what I’m reading?” he asked. “Especially Robin Hood?”

“You know how I volunteer at the library? Well, the librarians are all scared silly. A librarian up in Massachusetts refused to take a loyalty oath and a group called ‘Alert Americans’ raised such a ruckus about it that the county actually fired the poor woman.

“So to be safe, our librarians made a list of books we might have to pull from the shelves. It includes Robin Hood.”

“But why?”

“Because Robin Hood takes from the rich to give to the poor.” She added in a whisper as if they could be overheard: “That’s a communist concept.”