[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves ]

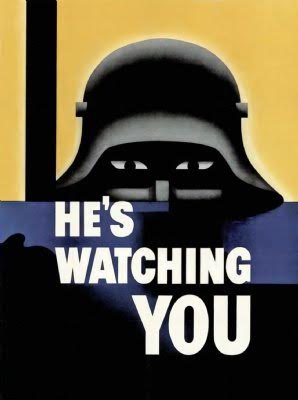

Nazi Uboats off our East Coast

Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves

Hitler’s U-boats struck at night. Their crews easily spotted the silhouettes of American vessels backlit by the illuminated skylines of East Coast cities, and then sank them, without warning, often with just one torpedo and within fifteen minutes of the hit. Not anticipating attacks on our own territory, the United States was woefully ill prepared to protect ships and crew or to fight back—short on spotter planes, modern warships, anti-submarine weaponry, and training. Half the US Navy warships were in the Pacific, and fourteen of those had been severely damaged during Pearl Harbor. Compounding the problem was the fact that two years earlier, to help shore up Britain, we’d sent them 50 WWI-era destroyers in exchange for land-leases in Newfoundland, Bermuda, and the British West Indies. All we had left in the Atlantic fleet were a dozen old destroyers and small Coast Guard cutters to patrol 28,000 miles of shoreline from Florida to Maine.

As a result, most merchant ships traveled our coastal water shipping lanes unescorted, essentially sitting duck targets.

From January to July 1942—before states and the federal government mandated nightly blackouts, before our radar and sonar were effective, before observation towers could be built, before aircrew and the Coast Guard were well-trained in locating and combatting U-boats hidden in the ocean—a mere five Nazi U-boats managed to sink 397 freighters and tankers off our coast. A million tons of cargo destroyed, dozens of Americans lost each night, those who survived their ship’s blast often drifting on the open seas for days before being rescued.

In the month of March alone, Hitler’s U-boats sank 33 tankers, freighters, and cargo ships a week, one every eight hours, most within sight of land. Triumphant, Nazis crews called it “The Happy Time” and “the Great American Turkey Shoot.”

Hitler’s primary targets were New York and the opening of the Chesapeake Bay in southern Virginia, at Norfolk-Hampton Roads. Not only was that area an enormous commercial shipping center, it was home to half a dozen military bases as well as shipyards and factories quickly converted to producing wartime armaments. Residents from Tidewater Virginia to the Outer Banks of North Carolina dealt constantly with oil slicks, debris, and sometimes even broken bodies washing up in their inlets and beaches. Some grimly joked they could read at night by the glow of ships burning a few miles out to sea.

It wasn’t until April that American sailors spotted and successfully battled a U-boat. The USS Jesse Roper, a patrolling WWI-vintage destroyer, unleashed a barrage of depth charges to sink U-85 near Cape Hatteras, NC. Our Navy buried the German U-boat crew with full honors in Virginia’s Hampton National Cemetery as I describe my characters Louisa June and her big sister Katie witnessing in Chapter Thirteen.

Some German captains would throw water or provisions to survivors before submerging and disappearing into the dark waters to continue their hunt. One of the most poignant examples of such mercy is the Laconia incident, when U-156 sank a British ocean liner it suspected of transporting troops and supplies, only to discover the vessel was carrying hundreds of civilian passengers as well. Captain Werner Hartenstein rescued them, taking many on board and tethering to his U-boat several lifeboats crammed with survivors. Staying on the surface and exposing his own submarine while negotiating with the Allies to come take its civilians, however, the U-boat was attacked by an American bomber. (If you’re interested, there is a marvelous two-part BBC TV movie, The Sinking of the Laconia.)

Other U-boat captains were ruthless. Many of my novel’s events were inspired by a particularly brutal attack by U-754 on a 140-foot tugboat, the Menominee, on March 31, 1942. After blasting the tugboat’s cabin and destroying its radio so the crew could not report the U-boat’s presence and after sinking the three barges of coal and lumber the tug was towing—thereby achieving his mission to eliminate fuel and supplies—Captain Johannes Oestermann ordered his crew to finish off the Menominee. U-754 chased down and shelled the tugboat, setting it ablaze. The Menominee exploded seconds later as its crewmembers abandoned ship. Only a handful reached a life raft and lattice float. And only three of them survived the night until they were spotted the next morning by a tanker on its way to New York.

The crew of the tanker, The Northern Sun, knew they risked also being attacked by the U-boat, which could be lingering near the wreckage, submerged and invisible, watching for a new target. But it stopped anyway. A lifeboat was lowered. When its engine gave out, the young sailors manning it knew every passing moment was critical to the Menominee survivors in the frigid water and rowed so hard they snapped an oar. They found a seventeen-year-old boy clinging to the floatation’s wooden latticework so desperately, his rescuers had to pry his fingers loose. Heartbreakingly, after the crew battled to “to get the water out of him,” the teenage sailor died in the tanker’s sickbay from a broken neck and severed spinal cord. It had been his very first voyage.

There were two sets of fathers-and-sons on the Menominee. The captain and his son, an able seaman; and the cook and his, a messman. Both sons were 22-years-old. Neither survived. One of them, messman George A Lawson, would later have a Liberty Ship named for him—one of the eighteen Liberty Ships named for African Americans.

Links on U-boats:

http://www.americainwwii.com/articles/sharks-in-american-waters/

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/17/obituaries/reinhard-hardegen-who-led-u-boats-to-americas-shore-dies-at-105.html https://uboat.net/maps/us_east_coast.htm

Links on the Menominee Tugboat attack:

https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/1486.html

https://www.amazon.com/Menominee-Lights-Sinking-Unarmed-Virginia-ebook/dp/B017OJH5KW