[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Da Vinci's Tiger ]

Women in the Renaissance

Da Vinci's Tiger

During the late 15th century, Florence experienced an exquisite metamorphosis, an unparalleled era of exuberant learning and artistic growth. The Renaissance was also a time of marvelous contradictions—like Ginevra says in the opening pages of DA VINCI’S TIGER—such as when devout Italians discovered classical Roman and Greek writings and incorporated “pagan” concepts and philosophies into theirs. Recast with new, more expansive wings of thought, Florentines, and then Europeans who followed them, took flight.

Suddenly, what we now call “humanism”—the study and celebration of the human experience and mankind’s capabilities—replaced the Middle Ages’ fearful focus on the afterlife and Catholic edicts about what brought about eternal damnation. The individual had voice. People reveled in rational debate and logic. With this intellectual liberation came an artistic reawakening that produced one of the richest, most productive periods in art history. Florence was saturated with famous artists making tremendous advancements in technique that brought a sophistication, physical accuracy, and expressiveness not seen in art since Ancient Greece. Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, Verrocchio, Botticelli, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael all worked and walked in those streets along the Arno River.

Ginevra de’ Benci exemplified the possibilities for women during the Renaissance, as its educated elite acknowledged that females had the same abilities as men to learn and to know what was right. But it took courage for women to seize that opportunity—and then eloquence, wit, and tenacity to hang onto it.

Here are some basic facts of Ginevra’s female contemporaries:

Only twelve percent of women in cities were literate. That number goes down to nearly zero out in the countryside. Think about this in the most basic terms—the overwhelming majority of women could not read or write even their own names.

Women were property, first of their fathers and then of their husbands. Marriages were financial transactions, negotiated to bring her family advantageous business and social alliances. Brides (and their dowries) were merely the bargaining chip. Younger sisters often ended up in convents because their families used up all their dowry funds for older daughters. Without a dowry, a woman was not really considered worth marrying. As a result nearly one in six women in Florence became nuns.

Cloisters could be happy refuges, however. Many convents were like Le Murate—intellectual sanctuaries where women could express themselves and study. This began when young girls were sent as boarders to “learn the virtues” of composure and chaste deportment before they re-emerged and married. But in some convents, students learned Latin, Greek, and writing as well. Upper class girls also studied dancing, singing, etiquette, cooking skills, and basic nursing—how to mend a broken limb, brew herbs, and treat fevers. Many learned to play harp, zither, or lute. Astronomy and math were considered “unfeminine,” according to Leonardo Bruni, who wrote the first treatise on women’s education. But he did think history a good topic for them. Overall, the purpose in girls’ education was to learn to run a household, to maintain a religiously devout home, and to give birth. Further study had the primary benefit of enlivening husbands’ lives with charming and informed discourse.

In some instances, daughters who remained cloistered might have been the luckier ones. Nuns in the more progressive convents wrote poems, devotionals, and dramas celebrating holidays, or painted illuminated manuscripts or altarpieces. Their married sisters, on the other hand, were expected to subjugate themselves to their husband and their ambitions to domestic chores. Marriage chests, while holding beautiful and lavish trousseaus also carried paintings that preached the proper attitude for new wives. Sometimes these scenes featured Venus and cupids, but more often they were depictions of obedience. One of the favorite historic events chosen was the abduction of the Sabine women, a legend Florentines interpreted as proving women could help reconciliation between two enemies by succumbing and beginning a new, co-mingled lineage.

Of course, marriages could be happy and mutually respectful. But in many cases, they were golden cages for wives.

A woman’s chastity was a critical badge of honor, for her and her family. The slightest unconventional act could start rumors. In DA VINCI’S TIGER, you will read of Ginevra’s uncle, Bartolomeo, leading a parade of young men to the palazzo of Marietta Strozzi to serenade and honor her. The men even pulled a float of a bleeding heart and set it on fire. It was snowing, and in youthful enthusiasm, the young men gleefully threw snowballs at her window. In fun, she tossed some back. That act of teenage frivolity raised suspicion of her being immodest. So much so a brother of a suitor cautioned him that even though Marietta was beautiful and rich, the possibility of “stain outweighed even these advantages.”

By law, husbands had the right to beat wives to correct faulty behavior or attitude. Defiant women also ran the risk of being accused of witchcraft. Chores like spinning and needlework were thought to bring spiritual as well as practical benefits—popular opinion held that idleness engendered gossip or meddling in husbands’ business. Typically when upper class husbands died, their property passed to their sons. Widows could be destitute unless their sons or sons-in-law supported them. Most husbands were much older than their brides. A very young widow might return to her family of origin, her dowry returned to her. But her children would be raised by her husband’s extended family.

Things were a little different for the working class within Florence’s merchant-society. Widows of craftsmen could carry on their husband’s business and become members of their trade guild in his place. In that regard, at least, it could be better to be a peasant.

Mostly, women were deemed inferior—physically, mentally, and morally—and prone to sin and corrupting men. The Bible, and popular writers like Boccaccio and Alberti perpetuated that belief. Even newly rediscovered ancient writings that sparked the Renaissance could paint women as lesser beings. Aristotle declared women defective males with compromised moral character. Popular belief held that “the female gaze” could inflame a man’s carnal desire, cutting him off from God and salvation. Respectable well-born girls, then, could not stand at a window for long, and typically only left their dwellings veiled and with an escort.

That was Ginevra’s universe.

Before I tell you of remarkable women who defied these definitions, I need to praise some men. Renaissance feminism—best defined in the 15th and 16th centuries as the argument for female dignity and equal innate abilities—began in highly literate homes, with humanist fathers who educated and talked to their daughters.

Remember, one of the primary glories of the Renaissance was the shift from Medieval superstitions and unquestioning reliance on the church to know how to behave. In the Renaissance, mankind began to think again. Education became the path to wisdom and, therefore, virtue.

In response, many wealthy families became their own little academies. They purchased manuscripts, recited poetry at dinner, commissioned art, and gathered philosophers at their table. Wonderfully, a growing number of fathers extended the ennobling gift of books and tutors to their daughters. Girls might read Dante, Virgil, Petrarch, St. Augustine, Plutarch, Ovid, and Horace, along with Cicero and Seneca who preached the seven virtues. These humanist dads not only took pride in their daughters’ abilities (or that of their mothers, wives, and sisters) but they also publicized it. They knew their womens' accomplishments aggrandized their home in general, and linked them in reputation to other intellectual men.

Within this milieu, Neoplatonic philosophy held that a woman’s graceful, physical beauty was evidence of deep inner virtues. It was a Christian twist on Plato’s concept that tangible things were reflections of greater truths. Therefore, a lovely woman could be a Platonic, spiritual muse who could save a man’s soul. Lorenzo de’ Medici and his circle proclaimed a man grew closer to God by gazing upon and contemplating such a woman, devoting himself to celebrating her in a nonphysical love affair. Just as Venetian ambassador Bernardo Bembo did Ginevra.

All these things helped foster a wondrous new cultural persona within the literati circles of high society: the learned, virtuous woman.

Even so, it took a daring woman to actually live and personify that ideal. Some men did indeed consider women their equal (or even their betters in terms of innate virtue) and relished peer-to-peer dialogue with them. Most in the general populace didn’t. Others saw the learned woman as entertaining rarities and as long as they didn’t talk too much, too loudly, too proudly, or become too insistent about their opinion, they were accepted and applauded. Cautioned Leonardo Bruni: “If a woman throws her arms around whilst speaking, or if she increases the volume of her speech with greater forcefulness, she will appear threateningly insane and requiring restraint.”

So, it took a brave and clever woman during the Italian Renaissance to recognize both the opportunities and the limits, and to negotiate that gauntlet in order to find her own voice and to sing out—as the prioress Scholastica inspires Ginevra to do in DA VINCI’S TIGER.

Here are some of them:

WRITERS:

Christine de Pizan (1365-1431) is the first woman we know of to make her living by writing, supporting herself, her mother, and her three children after her husband died. A poet, historian, theologian, and political essayist, her most famous work is the Book of the City of Ladies. In it, Christine makes the case for educating women, arguing they had the same inborn aptitude as men, were ethical and positive contributors to society, and that education would help feed and perpetuate that in them. Her work served as a literary bridge between Medieval and Renaissance thought.

In City of Ladies, Christine takes on the courtly love tradition popular in the Middle Ages crusades, in which aristocratic women were presented as icons for men’s admiration and quests yet also vilified as being unfaithful in their marriages and locked in chastity belts. Using rhetoric tactics she’d learned from her physician father, Christine basically stated that just because someone puts a good thing (in this case a woman) to bad use does not make that thing intrinsically bad. The Ladies Philosophy, Reason, Rectitude, and Justice all appear in the book to help Christine create a city of feminine accomplishment, populating it with a long line of virtuous, steadfast women from history, both classical and Christian.

Christine essentially invented what we know today as “women’s studies.” Her challenge still resonates after seven centuries: “All of you, my ladies—whether you are women of great, middling, or humble station—above all else be on your guard and vigilant in defending yourselves…. Let the luster of your virtue make liars of (those) who accuse you of heinous vices!”

Christine presenting her book to Isabeau, the Queen of France.

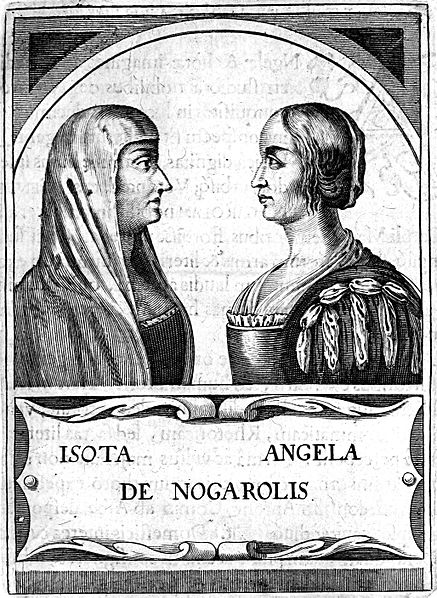

Isotta Nogarola (1418-1466) was the first woman to exchange letters with the most important male philosophers of her era. She impressed them by writing in direct Latin prose, rather than poetry or allegory. In her Dialogue, Isotta dared to defend Eve, trying to absolve her from blame for the fall of man. She argued Adam was more culpable, because God created Eve as an imperfect and less intelligent being than Adam. Therefore, his eating the apple was a conscious defiance, while hers was basically just a stupid, gullible mistake. Her reasoning doesn’t sit well with us today, but in 15th century Italy it sparked groundbreaking conversation. Isotta also spoke publicly, giving two orations in Verona during the installation of a new bishop.

She was a witty, passionate intellectual. When one scholar proposed that women only outdid men in talkativeness, Isotta quipped that “to make such an accusation was to condemn all women on the strength of a few.” She went on in her letter to list women who had lead armies as proof of female abilities. Unfortunately, an anonymous pamphleteer condemned Isotta as being vain and self-aggrandizing, and that her hunger for dialogue with male scholars hinted she was immodest in other aspects as well. After that, Isotta withdrew into a book-lined cell within her childhood home, to continue her studies in a kind of religious retreat.

Veronica Gambara (1485-1550) The grandniece of Isotta Nogorola, Veronica married the lord of Corrreggio, a small kingdom known for its refined, arts-filled court. When her husband died, Veronica became Correggio’s de facto ruler, even planning military strategies to fend off invasions. Unlike her aunt Isotta, a fierce warrior-woman reputation won Veronica praise as a savvy and admirable virago, (a strong-willed woman with statue, strength, and courage). This during a time Italy was in constant upheaval and battles with France and Spain. A poet as well as a patron of the arts, Veronica wrote in the style of Petrarch, lacing in many references to classical themes and to nature. Her love poems for her husband were set to music and her verses about grieving after his death are touchingly beautiful.

Veronica Gambara (1485–1550). Painting by Antonio da Correggio about 1517 -1520, The Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Cassandra Fedele (1465-1558) was taught Latin and Greek by her father, who was part of the working middle class in Venice. Because she was so precocious in her language abilities, she was invited to recite orations at the University of Padua and to the Doge, the city’s head of state. Young and beautiful, Cassandra so impressed the Venetian ruler that he invited her and her father to many banquets of poets, writers, and other literati, at which she recited Latin works. Her self-deprecating rhetoric charmed listeners. Cassandra also wrote to other women literati—the queen of Aragon, the duchess of Milan, the duchess of Ferrara, and the queen of Hungary—creating a kind of sorority of intellectual sisterhood.

When Isabella of Aragon invited Cassandra to join her court, the Venetian Senate issued a decree forbidding it, naming her as one of the city’s symbols of excellence. Florence’s poet Angelo Poliziano, who immortalized Simonetta and Giuliano de’ Medici in his Stanze, called Cassandra one of Italy’s loveliest ornaments. When she was thirty-four, Cassandra was married to a physician. We hear nothing more from her until she was quite elderly, when she begged the Venetian Senate to appoint her prioress of the orphanage attached to the church of San Domenico di Castello. Almost ten years later, in 1556, at the age of 91, Cassandra delivered a Latin oration at the state visit of the Queen of Poland.

Laura Cereta (1469-1499) was educated by nuns and came in and out of the cloister throughout her life. An astrologer, mathematician, poet, and orator, she was more defiant and outspoken than her predecessors in stating that education is the right of all human beings—male or female. She denied being exceptional because she was an intellectual, arguing that all women have the same capacities. In her letters, she chided women who weren’t educated, saying they could only blame themselves for a lack of schooling. She also warned her female peers that individual gossiping harmed all women, and that being slaves to fashion would make them slaves to men’s opinions. She was married at fifteen, but her husband died within a year and a half. Laura returned to the convent by the time she was 20-years-old.

Isabella Andreini (1562-1604) was a poet, humanist, and the most famous actress of her time. Perhaps illegitimate, she may have had to run away from home in order to join the Gelosi—a well-known commedia dell’arte theatre company in Bologna—when she was a teenager. Mainly playing the romantic prima donna on stage, she married another company member, Francesco, who had spent eight years in a Turkish prison. Despite the hardships of their youth, the couple became prolific writers of the highest caliber. They were devoted to one another, co-authoring some works. Isabella was fluent in several languages, and dared to write in the male voice as well as female. In her Lettere, for instance, she wrote a courtly love letter from the point of view of a young man. She often starred in her own plays, the most famous being Isabella’s Madness, which she performed at the wedding of Ferdinand I de’ Medici and Christine of Lorraine in 1589. Isabella had seven children, and there is evidence her husband becoming essentially a stay-at-home dad to support her stage career. Isabella died from complications at the birth of her eighth baby.

Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici (1425-1482) the mother of Lorenzo and Giuliano, she was a well known poet of devotional works. In addition to writing and supporting her husband and sons’ political careers, Lucrezia funded convents, gave dowries to orphaned girls, and ran a business—a medicinal hot spring. She also encouraged other poets such as Luigi Pulci. His Morgante Maggiore is believed to be one of the greatest writings of 15th century Italy. Most historians credit Lucrezia with being the overriding influence on her son, Lorenzo the Magnificent, raising him to be a poet, philosopher, and the greatest patron of the Renaissance.

Lucrezia Tournabuoni de’ Medici; Domenico Ghirlandaio, before 1475

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Vittoria Colonna (1492-1547) was married to the marquis of Pescara, She was a poet, intellect, religious reformer, and Platonic muse to Michelangelo. For her, the great artist wrote some of his most moving verse.

Gaspara Stampa (1523-1554) With her two sisters, who were renowned for their singing and lute-playing, Gaspara learned Latin, Greek, metrics, and music. She too was praised as a virtuosa in her native Venice, but is best known for the passionate poetry she wrote to her noble-born lover, Count Collaltino di Collalto. Gaspara tried to overcome the social distance between them through her verse, in which she both celebrated and agonized over their relationship, loosely following the style of Petrarch’s poems to his beloved Laura. Sadly, their stormy relationship ended badly. Her sister had Gaspara’s Rime published but it did not fair well, given Gaspara’s unconventional lifestyle. Today, however, Gaspara is hailed as one of Italy’s greatest poets.

For more information about these writers, see:

VISUAL ARTISTS

Onorata Rodiana (1403-1452) may be mostly legend. Born in Castelleone, Onorata was called to the Cremona palace by the Marquis Gabrino Fondolo to paint decorative frescoes. Attacked by a courtier, Onorata is said to have fought him off and fatally stabbed him. Fearing she would be executed, she dressed as a boy and escaped to the mountains. Remaining in disguise, she joined a band of mercenary soldiers or condottieri. At first, Fondolo tried to hunt her down, but eventually, wanting the paintings finished, he pardoned her. Only then did she return. Onorato completed the paintings and then returned to her life as a boy-soldier. In 1452, she helped defend her home village against invading Venetian troops, but was mortally wounded. Legend has it only then did the villagers recognize who she was, as she spoke her last words: “Honored I lived, honored I die.”

Properzia de Rossi (1490-1530) is the first known woman sculptor. Growing up in Bologna, she began by carving tiny religious scenes into the pits of peaches and apricots. She studied with a master engraver and at the University of Bologna, and won a commission to carve a marble relief panel of the Biblical story of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife on the west façade of San Petronio. She was included in Giorgio Vasari’s famous collective biography of artists in 1550.

Suor Plautilla Nelli , (1524-1588) was the first known female painter of Florence. Born into a wealthy cloth merchant family, she became a nun when 14-years-old, joining Santa Caterina da Siena. The convent was managed by the Dominican friars of San Marco—an order led by Savonarola, the fanatical monk whose railings against greed and luxury nearly destroyed Florence. Savonarola advised religious women to create devotional paintings and drawings as a way to avoid sloth. As a result, the convent became a kind of center for nun-artists. While Plautilla Nelli studied with a male Dominican friar, she was primarily self-taught. She produced large religious frescoes, lunettes, and canvasses, remarkable in the emotions and compassion she was able to convey in her female faces. She even painted a large Last Supper (see below) and signed it with pride, adding: “Pray for the Paintress.” Her works have only recently been rediscovered and restored. For more information, see: wfyi.org/programs/invisible-women-forgotten-artists-of-florence/television/invisible-women

Lamentation with Saints

Pained Madonna

The Last Supper, 6.7 meter long oil-on-canvas preserved in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella.

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was born in Cremona and educated in Latin, music, and painting. She was apprenticed to Bernardo Campi when she was 11-years-old. Michelangelo is said to have been so impressed with her that he sent her drawing of a crying boy to the Medici. She became known for portraits and realistic family scenes. In 1559, King Philip II of Spain invited her to Madrid as painter and lady-in-waiting to his wife, Isabella. When Anguissola eventually returned to Genoa she created a painting school. For more information: youtu.be/fDFN1ZteJ0k

The artist's sisters Lucia, Minerva and Europa Anguissola Playing Chess, 1555

Self-Portrait, 1556, Lancut Museum, Poland

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) grew up in Bologna, the daughter of a fresco artist who trained and encouraged her. Influenced by Raphael and Sofonisba Aguissola, Lavinia was a prolific artist, amassing the largest body of works by one female before 1700, and becoming the official portrait painter of Pope Clement VIII. She married another painter and gave birth to eleven children.

Lavinia, Self-Portrait at the Clavichord with a Servant, c. 1577, Oil on canvas

Marietta Robusti (1552-1590) was the daughter of Venetian painter, Jacopo “Tintoretto,” and was an accomplished portrait painter. Her father loved her so dearly, he disguised her as a boy until she was 15-years-old so she accompany him to his work.

Possible Self-portrait with a spinnet, Uffizi

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1653) actually falls into the Baroque period. But I include her because she is arguably the best-known Italian female artist, producing grand scale and moving narrative works of biblical tales and mythology. She was the first female invited to join Florence’s Academy of Art and Design, an honor made even more remarkable given the horrific challenges of her youth. Artemisia had trained with her father initially, but was raped by her drawing master when she was fifteen years old. Testifying in his trial, Artemisia was tortured with tightening metal rings on her fingers in an effort to force her to recant. Artemisia moved to Florence afterward and flourished artistically, depicting strong and expressive women in the most challenging and heroic of moments.

Judith and her Maidservant (1613–14) by Artemisia Oil on canvas Palazzo Pitti, Florence

ARTS PATRONS

Isabella d’Este (1474-1539) was the eldest daughter of the rulers of Ferrara, Ercole I and Eleanor of Aragon, who were generous patrons of the arts. Isabella carried on that tradition when she married and ruled Mantua. Educated in Greek and Latin, an accomplished lutist and dancer, Isabella presided over gatherings of artists and scholars, filling the castle library with books. Noble women throughout Italy emulated her way of dressing. She also mixed her own fragrances. But Isabella’s greatest artistic love was music. She nurtured secular composers and employed female singers at her court.

When her husband was captured and held hostage in Venice, Isabella led Mantua's military forces, defended the kingdom against invasion, and rode to Milan to negotiate with the king of France. Evidently her husband was humiliated by her political acumen and ability to negotiate his release. Isabella responded to his rage by traveling and living independently, mostly in Rome, where she met and encouraged many artists. She gave birth to eight children, and helped build Mantua into a Duchy during a time Italy’s many city-states fought one another for power and territory. Her portrait was painted by Titian and drawn by Leonardo.

Titian painted Isabella when she was in her 60s, but she insisted he redo his portrait to reflect how she looked 40 years younger.

Beatrice d'Este (1475-1497) was the younger sister of Isabella, and also a well-educated intellectual, a skilled diplomat, and patron of the arts. She was married to the duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. She knew Leonardo da Vinci, who reportedly orchestrated their wedding, and who served her husband as engineer and court musician, before painting portraits of Ludovico's mistresses. Witty and an accomplished equestrian, Beatrice rode to Venice as her husband's ambassador and also was present at the peace congress of Vercelli between Charles VIII of France and the Italian princes. She died, however, at age 21, during childbirth. Her portrait was painted by Ambrogio de Predis, although some speculate that the work might in fact be by Leonardo.

Beatrice, attributed to Ambrogio de Predis, although some speculate Leonardo actually painted this portrait.

Leonardo's Other Female Portraits

Ginevra de’ Benci was the first of four female portraits universally attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. Here are the others:

Portrait of a Lady with Ermine

The lady is believed to be Cecilia Gallerani, a leading literati in Milan. She was also mistress to the ruling duke, Ludovico Sforza, known as il Moro. A poet, musician, and singer, Cecilia reportedly hosted gatherings of philosophers and perhaps invited Leonardo to their discussions when he served the duke. She was about sixteen years old when the portrait was painted. Cecilia bore Sforza a son, and eventually was forced out of the castle when he married Beatrice d’Este. Cecilia then married Count Ludovico Carminati de' Brambilla and had four more children.

Like the juniper bush behind Ginevra, the ermine in Cecilia’s arms carries many meanings and perhaps is a pun on her name since the ancient Greek name for ermine is galee. Legend held that ermines would rather die than soil the pure white color of their winter coat, so the animal became a symbol of purity. Aristocrats often kept ermines as pets, so perhaps Cecilia did as well. The ermine certainly identified the patron of the portrait—Ludovico had been admitted to the Order of the Ermine, a chivalric fraternity, in 1488.

La Belle Ferronniere

This portrait earns its descriptive name from the ornamental band around the sitter’s forehead. She is believed to be Lucrezia Crivelli (1452- 1508) another mistress of Ludovico Sforza, and the mother of his son, Giovani. Crivelli had been a lady-in-waiting to Sforza's wife, Beatrice d'Este. Ironically, after Beatrice died, Crivelli lived for many years in Mantua under the protection of Beatrice’s older sister, Isabella. Tests show that this portrait and Lady with an Ermine were painted on wood panels cut from the same tree trunk. Some scholars speculate that this portrait might actually be Beatrice d’Este rather than Crivelli.

Isabella d’Este

The painting may be a completed version of a pencil sketch drawn by Leonardo da Vinci in Mantua in 1499

Leonardo sketched Isabella d’Este, Marchessa of Mantua, around 1499.

Recently a painted version of the drawing was discovered in a Swiss bank fault. Scholars are debating if Leonardo did the painted version.

Isabella was a great patron of the arts. Educated in Greek and Latin, an accomplished lute-player and dancer, Isabella presided over gatherings of artists and scholars, filling the castle library with books (see her entry above for more detail).

La Bella Principessa

This chalk and ink drawing of a young fiancée in Milan may have been done by Leonardo in the mid-1490s.

Mona Lisa or La Gioconda

The most recognized painting in the world (the second being Van Gogh’s Starry Night) Leonardo started this painting in 1503, while still in Florence. This portrait is thought to be of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant named Francesco del Giocondo. But Leonardo took it with him to France, rather than giving it to her family. No one knows exactly how long he took to paint it, or for what occasion (or reason) he painted it. Much of the Mona Lisa’s fame comes from the way her eyes seem to follow the viewer no matter where he or she stands. Her enigmatic smile has also intrigued us for centuries. According to the Louvre, where the portrait hangs, her smile is as much an identifying emblem as the juniper bush, or ginepro, in the portrait, Ginevra de’ Benci. In later latin, the word gioconda, suggests pleasant, delightful, happy.

For more information:

musee.louvre.fr/oal/joconde/indexEN.html

pbs.org/treasuresoftheworld/a_nav/mona_nav/main_monafrm.html

An exquisitely detailed story of the passionate relationship between artist and muse, whose spirited yet gentle Renaissance heroine put me in awe of just how far women have had to come in 500 years. Beautifully painted.

Elizabeth Wein, Printz Honor winner and NY Times bestselling author of Code Name Verity