Laura's Blog

The Teacher Behind Leonardo

April 16, 2016

Behind almost every important thinker or artist is a nurturing teacher. Leonardo da Vinci is no exception. His all-important mentor was Andrea del Verrocchio.

Like Leonardo, Andrea di Michele di Francesco de’ Cioni was illegitimate. His father was a fornaciaio, a kiln worker, and Verrocchio may have worked with clay and stone as a young boy. Then he was apprenticed and adopted the name of his master—Giuliano Verrocchio—which translates to “true eye.” He also studied with painter Filippo Lippi, and may have apprenticed for a time with the legendary Donatello.

Over the years, Verrocchio’s talents and accomplishments have been overshadowed by his famous student’s. But in the 1470s, Verrocchio was one of the most acclaimed and sought after artists in the city, remarkable in his output and diversity, a goldsmith, engineer, sculptor, and painter. He was a favorite of the Medici, who commissioned many pieces from him over two decades. As a result, his studio, or bottega, was the busiest in the city, nurturing many younger artists including Botticelli, Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, and Ghirlandaio (who would later train Michelangelo).

In Verrocchio’s bottega, Leonardo would have learned all the basics—perspective, how to mix paints, sketch, caste bronzes, model in wax and clay, and to sculpt. He would have started as a dogsbody, sweeping the floors, crushing colors at a grindstone, making brushes with boar’s bristles, and stoking the fires that would melt gold, copy, and bronze for art pieces.

Education in Renaissance studios was collaborative and hands-on, meaning apprentices worked side-by-side with the master artist, generating commissioned works as quickly as possible. When Leonardo was 19-years-old, Verrocchio created a gilded copper sphere, eight feet in diameter to crown the copula of the Duomo, one of the architectural and engineering wonders of Christendom. (see my webpage for more about Brunelleschi and his dome https://lmelliott.com/book_landing_page_historical/da-vincis-tiger/links-learning-more-da-vincis-tiger/ ) That would have been an all-hands-on-deck project to fashion the mechanical hoist to lift the orb up 300 feet and safely secure it.

In his early 20s, Leonardo added many touches to Verrocchio’s paintings. Together they painted a banner for the Joust of 1475, (which opens the novel) and we do have the preliminary sketches for it. A consummate botanist, Leonardo probably created the millet stalks to the left of the sleeping nymph. (The plants symbolized fidelity).

In Tobias and the Angel, it is believed he painted Tobias’ curls, the little white Bolognese terrier prancing beside him, and the fish he held. (Art historians can make these attributions because of telltale left-handed brush-marks.)

In Baptism of Christ, Leonardo painted the subtler aspects of the landscape, the transparent water and plants below, and the angel on the far left, looking adoringly at Christ. Legend has it that after seeing Leonardo’s beautifully rendered angel Verrocchio gave up painting altogether.

Verrocchio’s forte and fame rested largely in his sculpture, which had a palpable emotional life. Verrocchio believed that creating motion and realistic gestures conveyed thoughts, feelings, and drama. Take one of his most famous bronze statutes, the Christ and St. Thomas (or “Doubting Thomas”). Through the figure’s movement, Verrocchio vividly shows the discipline’s crisis of faith. Thomas reaches out to touch the gaping wound left by a soldier’s spear in Jesus’ side to prove to himself here indeed stands a resurrected Christ. Jesus raises his arm to allow the inspection, in poignant patience with Thomas’ doubt.

Verrocchio told his apprentices to “know the bones and muscles underlying the clothes” to build a body “from the inside out.” And certainly the sweeping motion of Thomas’s robes, the hint of leg underneath, depicts a sudden, anxious movement.

Such artistic philosophies may have helped fuel Leonardo’s fascination with anatomy.

Verrocchio believed hands particularly expressive. This is perhaps most beautifully displayed in Verrocchio’s marble sculpture, Lady with Primroses. He carved it about the time Leonardo painted Ginevra de’ Benci. Just as Leonardo’s portrait of the young poet was groundbreaking, so too was Verrocchio’s sculpture.

Lady with Primroses was the first Italian portrait sculpture to extend below the shoulders, making it far more evocative of the lady’s heart and soul. The figure appears to have just gathered up flowers in the way Verrocchio carved her hands and turned her shoulders. In a gesture of modesty? Surprise? Affection, if the flowers came from her lover?

Many suspect Ginevra de’ Benci might also have been the subject of this marble statue. The face, dress, and hairstyle of the two art pieces are strikingly similar, and the figure in the statue cradles blossoms that may have been referenced in one of the poems written about Ginevra, commissioned by Bernardo Bembo, the ambassador scholars now agree hired Leonardo to paint her portrait. Primroses were also part of Bembo’s family crest.

Strengthening the hypothesis that Ginevra was the model for both works is the fact Leonardo’s painted Ginevra may originally have held blossoms in a pose similar to Verrocchio’s statue. At some point, the bottom third of Ginevra’s portrait was cut off. A study of hands with a sprig of flowers sketched by Leonardo is the basis for the assumption the missing portion of the painting showed her holding blossoms.

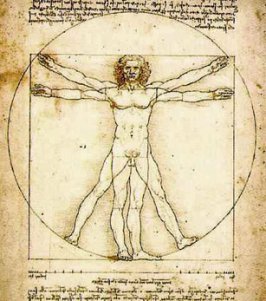

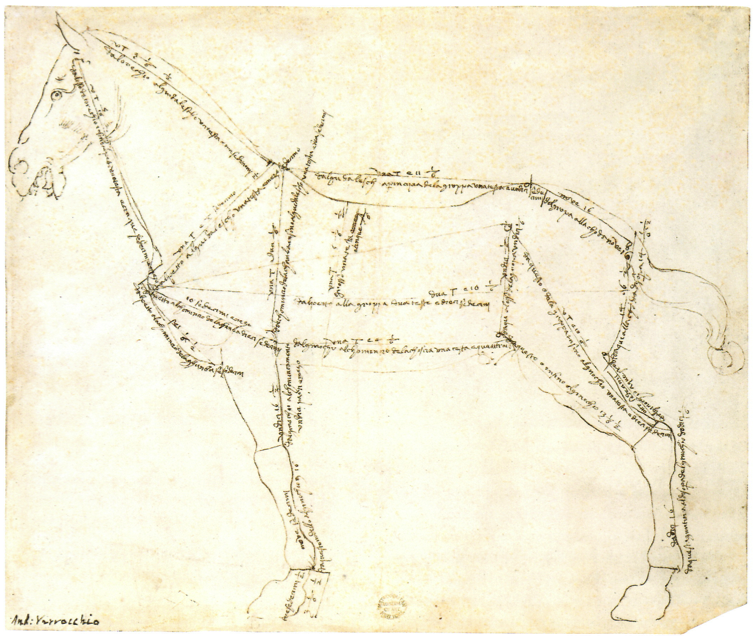

Verrocchio’s influence on Leonardo was vast. Many scholars now speculate that several artistic innovations once credited solely to Leonardo—such as the subtle blending of light and shade called sfumato—might actually have been Verrocchio’s idea first. Leonardo’s famous Vitruvian Man—famous for the figure’s perfect proportions—followed Verrocchio’s sketch of a horse that included precise measurements of the steed’s limbs in proportion to one another.

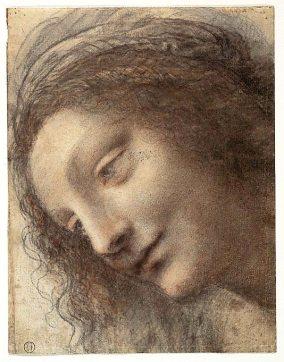

Clearly Leonardo emulated the charming and lovingly animated faces of women Verrocchio drew. And the statue Lady with the Primroses suggests shared inspiration, as do Verrocchio’s putto of a cherub hugging a dolphin and Leonardo’s toddler crushing a cat with affection.

The men must have been close friends. They had much in common—Verrocchio was also a musician, owned a lute, and sang. He was highly literate and owned a relatively large humanist library with works by Ovid and Petrarch. Leonardo eventually amassed quite a library himself and was a renowned musician.

The younger artist stayed in the master’s studio and home long beyond his apprenticeship. They both left Florence about the same time—Verrocchio heading to Venice to complete an enormous equestrian statue of Condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni and Leonardo for Milan, at first perhaps as a court musician, sent as emissary to the Sforza court by Lorenzo de’ Medici.

I, for one, was grateful to learn about Verrocchio—the teacher behind our most revered Renaissance Man. He was a man who worked hard to hone his skills and perfect his art if we are to believe the art biographer Vasari, who wrote that Verrocchio “acquired his talents rather by infinite study than by the facility of a natural gift.” If so, I applaud his exquisite output even more.

Thank you, Andrea, for helping Leonardo find his artistic voice and express it so magnificently!

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts