Laura's Blog

A Revolutionary Woman Journalist

July 11, 2018

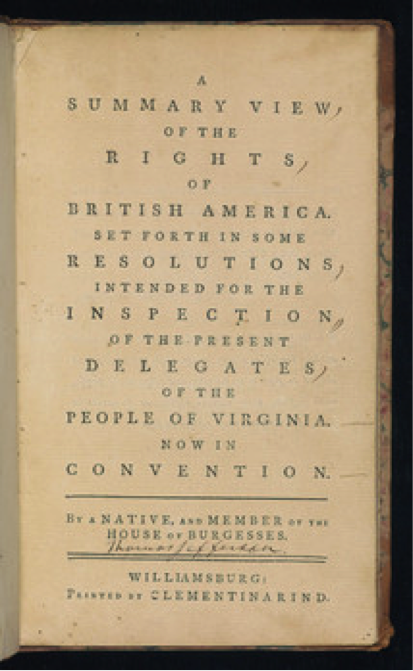

Today, for Women Crush Wednesday, let’s raise a coffee cup in honor of Clementina Rind, Virginia’s first female printer. In 1774—two years before the Declaration of Independence and when most people in the colonies were angry at the King’s taxes but still staunchly loyal to England—she had the guts to publish Thomas Jefferson’s A Summary View of the Rights of British America. Drafted as instructions to the Virginia delegates going to the First Continental Congress, TJ’s tract was a resounding list of grievances against Parliament and King George, a precursor to the declaration we all know and celebrate on the 4th of July.

Clementina took leadership of Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette at the death of her husband, without missing a single issue of their 4-page Thursday weekly. She wrote: “Being now unhappily forced to enter into upon Business on my own account, I flatter myself those Gentlemen who shall continue to oblige me with their Custom will not be offended at my requesting them, in future, to be punctual in sending Cash with Advertisements. “ Evidently Thomas Jefferson and George Washington were among the few who paid promptly!

Clementina kept printing even as her home and many of her possessions were sold to pay off her dead husband’s outstanding debts. She did manage to keep the printing press, however, and within a few months had turned her business around enough that was able to purchase “an elegant set of types from London.” She petitioned the House of Burgesses to continue granting her gazette their printing orders over a rival gazette published by Purdie and Dixon.

In her early 30s at the time, Clementina achieved all that while parenting four young sons and one daughter, named Maria (who is an important character in my other Revolutionary War novel, GIVE ME LIBERTY).

As editor, Clementina expanded the newspaper’s material to include not only news reports of foreign and domestic affairs, local politics, and shipping, but essays on scientific discoveries, the educational reforms at the College of William and Mary, and poems and prose celebrating female pursuits. She also addressed the welfare of widows and orphans. She proudly kept to the motto her husband had given the newspaper in 1766: “Open to ALL PARTIES, but influenced by NONE.”

In December 1773, her rival gazette ran an anonymous accusation that Clementina had violated her paper’s proclamation of unbiased free expression by refusing to publish a piece that libeled someone in town. Her response was that she might have if the author had been willing to name himself, especially since the article dealt with an incident that should be decided in a court of law rather than in her newspaper.

During her 13 brief months as printer, Clementina did help fuel Virginia’s growing revolutionary sensibilities by running articles that included patriot outrage at the British blockaded of Boston’s port, following the famous Sons of Liberty’s tea party. When the House of Burgesses passed a resolution for a day of fasting in solidarity with Boston, she published their call, as well as their commentary about the infringement on American liberties.

Sadly, Clementina became died in September 1774, at age 34, struck down with an undisclosed illness. She was sure to have remained an important voice and arbiter of political debate during the Revolution had she lived, reflected by the large number of eulogies and a 150-line elegy about her intellect, literary talent, and sound critical judgment. Even her printing rivals sung her praises in their obituary, calling her “a Lady of singular Merit, and universally esteemed.” One of them, John Dixon, actually became guardian to her orphaned children.

Her daughter Maria grew up to become a governess and married her charges’ tutor, John Coalter, who later became a judge with the Virginia Court of Appeals. One of Clementina’s sons became a lawyer in Kentucky, and another a Loyalist printer in Canada. William Rind eventually returned to the United States, publishing Richmond’s Virginia Federalist and Georgetown’s Washington Federalist—a pretty clear legacy of Clementina’s commitment to reporting all sides of an argument, even if she herself was a patriot!

If you’re interested in a historical fiction set in Williamsburg during this exact time period and in which the young Maria appears, check out my novel about a young apprentice who becomes a fifer in the 2nd VA Regiment just in time for the Battle of Great Bridge, south of Norfolk. http://www.lmelliott.com/book_landing_page_historical/give-me-liberty/

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts