[ Back to ] -> [ Back to Books for All Ages ]

FAQs About Laura

Where do you live?

In Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C.

How many children do you have?

Two! A daughter and a son, who have both grown up to be amazing creative artists themselves—one a theatre director, the other a novelist/screenwriter.

How many books have you written?

Twenty-one total. Fourteen YA, Middle-grade, and "new adult" novels; five picture books with illustrator Lynn Munsinger; and two adult nonfiction books I wrote when I was a magazine journalist.

How and when did you start writing?

How and when did you start writing?

Honestly, I can’t remember a time that I wasn’t scribbling down stories. I was lucky to have a healthy imagination like Storm Dog’s Ariel, and by elementary school I was writing stories on the old-timey onionskin typing paper my parents would staple into “books” for me. I do recall the loud scratch a well-sharpened pencil made on the crisp sheet, and that it was hard to erase my drawing boo-boos. Most of those stories included animals as “supporting characters,” something I still seem to do today. My illustrations were….well…. let’s just say I am incredibly lucky that my picture books are graced with the beautiful artwork of Lynn Munsinger! (https://www.encyclopedia.com/children/scholarly-magazines/munsinger-lynn-1951 )

I think what I instinctively loved about writing was it allowed me to ask all those “how-come” questions, like Alice in Flying South. “How-come” people act the way they do? Writing helps you explore and come to understand and then celebrate—or challenge the thinking of—the rather remarkable creatures that human beings are.

Frankly, I was a bit of a tomboy and spent most of my childhood romping through wildflower fields behind our home, climbing trees, and playing with our pets. I was lucky to live in one of the lusher parts of Virginia, where the hills roll green—so I was an outdoor child. But when I went indoors, a phenomenal library awaited me. I grew up in what had been my grandfather’s home. He was a commonwealth’s attorney (a prosecutor for the state, prone to quoting poets in his closing arguments), and an avid reader. I wish I had known him. But I felt a kinship with him through his vast collection of books. His study was filled with stories of adventure, chivalry, and quests. I grew up on retellings of Robin Hood; Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book; J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan; Robert Louis Stevenson poems and novels like Treasure Island; the real Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne with that wry humor and delight in childhood; C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, E.B. White’s Stuart Little and Trumpet of the Swan, T. H. White The Sword in the Stone, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and O’Henry’s short stories. These are often classified as “boy books” – thank goodness no one told me that!

I think that’s why I can write stories like Under a War-torn Sky, A Troubled Peace, Across A War-tossed Sea, or Give Me Liberty that feature male protagonists coming of age and following ideals of hope and courage, even amid the destruction and hatred of war. Or Suspect Red, exploring the impact of national politics and rhetoric on two teenage boys during McCarthyism, and Walls, following two cousins divided by the Cold War’s propaganda and dangers.

In that childhood library, I also found books my grandmother and mother loved, Little Women, Jane Austen’s dramas, Willa Cather’s My Antonia, and the Little House on the Prairie series, which told me to look for women of strength and resilience, wit and spontaneous ingenuity—no matter what constraints society put on them. A sixth sense that served me well as a journalist and when writing characters like Peggy (Hamilton and Peggy!); Ginevra (DaVinci’s Tiger); Madame Gaulloise, Claudette, and Patsy (Under a War-torn Sky); Cousin Belle (Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves); and Mrs. Scott (Bea and the New Deal Horse).

And, of course, there were "new" novels for youth like Scott O'Dell's wondrous Island of the Blue Dolphins that completely engrossed and transported me, opening my eyes to the magic of historical fiction. Which makes the fact Bea and the New Deal Horse just won the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction even more humbling and thrilling for me.

There were also poetry collections. Favorites were Wordsworth, Keats, Longfellow, and Emily Dickinson who celebrated the world’s small glories, like bees, “the buccaneers of buzz.” My mother read Charles Dickens novels aloud to us at night, dramatically changing her voice for each character. Listening to Dickens, I learned about the hook of cliffhanger chapter endings. I also met up with Shakespeare early, and if I didn’t understand the plot lines I simply relished the pictorial language. I very much wanted to be the faery Puck. I still sit down with some Shakespeare when I need to be inspired to write image-infused descriptions.

What other authors would you recommend young aspiring writers to read?

There are SO MANY wonderful writers now for young people. These are but a few suggestions:

For voice: Lindsay Eagan (she can even get into the head of a cathedral gargoyle!); Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, (her Shiloh trilogy and Alice series in particular), Kate DiCamillo, Lauren Volk, and Kwame Alexander.

For championing young people who triumph over tragic pasts or hidden personal challenges: Leslie Connor, Kathryn Erskine, Meg Medina, Walter Dean Myers, and Tiffany Jackson.

For compassionate humor: Jerry Spinelli, Christopher Paul Curtis, Carl Hiaasen, Madelyn Rosenberg, and Jane Leslie Conly. For anything to do with nature, and fanciful retelling of history through the witnessing eyes of animals, Henry Cole.

For nature-rich coming of age: Scott O'Dell, Jean Craighead George, Will Hobbs. For sports: Fred Bowen, Mike Lupica, and John Feinstein.

For historical fiction: Elizabeth Wein, Sharon Cameron, Amanda McKrinna, Monica Hesse, Laura Ruby, Jennifer Donnelly, Eugene Yelchin, Rita Sepetys, Laurie Halse Anderson, Karen Hesse, Ari, and Deborah Wiles.

For fantasy/dystopia: Veronica Roth and Tamara Pierce.

BUT there are hundreds more. In Storm Dog, Ariel has a reading list I’ve posted you might check out as well. Click here to check that out.

Because it’s fascinating! The odyssey of how we came to be what we are today. The choices, the challenges, the mistakes, the triumphs, the villains, the heroes.

I grew up just outside Washington D.C., very aware of history in the making. One of my earliest memories was of JFK’s tragic assassination. For days, my house boomed with the sound of anxious news broadcasts. Fast upon that came the killing of his brother Bobby and another man of eloquence, Martin Luther King, Jr. I came of age during the Vietnam War protests and then Watergate. It would have been impossible not to have a sense of events changing the world and the way people thought. This is why my first life was as a journalist. For twenty years, I was a senior writer with the Washingtonian magazine, after spending high school, college, and grad school working for student newspapers or “stringing” for local papers.

My own growing up was permeated with political discussions around our dinner table, witnessing demonstrations in D.C., and arguments, sometimes heated, with my peers regarding the slow-drip revelations about our troops in Vietnam and our elected officials during Watergate. So I am very aware of the trickle-down impact of national dialogue and polarization on teens and their friendships—themes I explore in Suspect Red (1950s’ McCarthyism), Walls (East/West Berlin during the Cold War), and Truth, Lies, and the Questions In Between (about 1973, the Watergate hearings and fight for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. To be released Jan. 2025)

But the real love of history probably started with my knowing as a small child a number of elderly ladies in what was then a small-town community. In their garden, over fresh-squeezed lemonade, they’d talk and talk in musical voices and long anecdotes. They told me of history—but not dates, battles, or political figures. It was personal, about how their relatives (or they) survived hard times, how mothers worried about their children during epidemics and wars, where they were when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and how they helped the war effort afterward. From them, I learned that history is a very human drama and that the way to make it captivating, truly enlightening, and oh-my-gosh-tell-me-what-happens-next-intriguing was to focus on one individual’s journey through turbulent, trying times.

Why do you set so many of your novels in Virginia?

The author Willa Cather said, “Let your fiction grow out of the land beneath your feet.” I didn’t set out to become a “Virginia-writer,” but so I have. Of my fourteen novels, ten are set entirely or partially in Virginia. It’s just fact that so much of early American history, political movements, and battles, occurred here. Bea and the New Deal Horse, Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves, Give Me Liberty, Flying South, Across a War-tossed Sea, and Annie, Between the States, are all rooted in the commonwealth’s experience during ground-shifting eras.

As I wrote, my contemporary narrative Storm Dog turned into a bit of a love song to the state. Part of that has to do with the solace and affinity Ariel instinctively feels out in nature—in the rolling green of Fauquier and Loudoun counties. Ariel goes to Sky Meadows State Park (a gorgeous 1,862-acre sanctuary up against the Blue Ridge) to escape her troubles, to have a hawk’s cloud-down perspective on the world, where she finds the ethereal and a sense of the divine—however you wish to define it—in a catbird’s song, the delicate design of a Spring-beauty’s tiny blossom, and in the winds that kiss the earth up on those hills. All things I grew up rejoicing in and still do.

With Storm Dog, geography also handed me a palpable push-pull between disparate but neighboring cultures and the poison of thinking in stereotypes. Within the 50-mile radius of Ariel’s world, in that northwest corner of Virginia, you will find elbowing each other: the diverse, international suburbs of D.C, designer-boutique luxury shopping meccas, and the million-dollar tract homes of the exurbs beginning to encroach on rural, 19th-century country estates where equestrians still “ride to the hounds” and working farms and orchards picked by recent immigrants or migrant workers, where plenty of people struggle to get by. As such, the area percolates with frictions and misunderstandings born of preconceptions and prejudices.

I never forget when I write for young people that they are still forming their own set of beliefs and fervently believe they can make a difference in this world if they just try hard enough. So it is a privilege to create characters who resolve some of these issues for themselves through personal exchanges and actually coming to know one another, to “show rather than tell” my readers how mighty and transformative for them and our ability to cooperate with one another such revelations can be.

It seems like music comes into your novels a lot. Why?

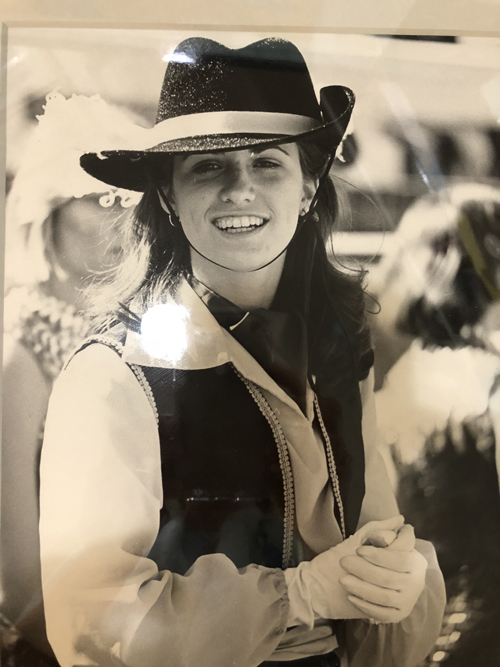

Music was my first love. I think nothing is as mystical or redemptive or more of a communion with the sublime in this universe or with one another. I play the flute, piccolo, and piano, minored in music in college, and was the field conductor of Wake Forest University’s marching band. (Love those Demon Deacons!) At that point, I hoped to perform or conduct classical music professionally. I promise, in terms of showmanship, camaraderie, and plain old fun, nothing beats being in a high school or college marching band. It comes from my heart when I have Ariel say: “If you’ve never seen a parade live—felt the street throb and your heart pulse in rhythm with a passing band’s drum cadence, been swept up in all the colors and confetti and celebration—promise yourself to do it before you die. Better yet, march in one.”

Music was my first love. I think nothing is as mystical or redemptive or more of a communion with the sublime in this universe or with one another. I play the flute, piccolo, and piano, minored in music in college, and was the field conductor of Wake Forest University’s marching band. (Love those Demon Deacons!) At that point, I hoped to perform or conduct classical music professionally. I promise, in terms of showmanship, camaraderie, and plain old fun, nothing beats being in a high school or college marching band. It comes from my heart when I have Ariel say: “If you’ve never seen a parade live—felt the street throb and your heart pulse in rhythm with a passing band’s drum cadence, been swept up in all the colors and confetti and celebration—promise yourself to do it before you die. Better yet, march in one.”

Ariel helps the runaway dog that saves her in a wild thunder-guster storm to find trust again through music and “dog-dancing.” (Yes, that’s a thing! See demos of it here: https://lmelliott.com/book-landing-page-contemporary/storm-dog/dogs-dogs-dogs-storm-dog .) The name she gives him comes from his reaction to Stevie Wonder’s marvelous tribute to big-band legend Duke Ellington in his song “Sir Duke.” You can listen to all the music that Ariel plays for Duke to get him happy here: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5DPXEe3w2Zn7PA17rp2dcc

I have also written about the historical importance of music—its use for protest or expression of changing attitudes in society—most directly in Give Me Liberty. Music has always been a way for humans to express and spread ideas and was particularly important as a political forum and as military signals during the American Revolution.

So too during the 1960s and '70s, which I highlight in WALLS and Truth, Lies, and the Questions In Between. Some of the most moving anecdotes I discovered in researching Cold War Berlin and the cruel Wall raised in 1961 to cage millions of East Germans had to do with the yearning for free expression behind Soviet Russia's "Iron Curtain." So much so that when we tried "cultural diplomacy," sending American jazz musicians to perform in communist-controlled Eastern Europe, a few young people there dared arrest and time in "re-education labor camps" to secretly record those performances. The only way they could preserve the music they so longed to hear was to record onto discarded X-ray films pulled out of trash bins. Cut into record-like discs, the shadowy images of lungs and hearts were still visible. As one of my characters says: "Music recorded on chest X-rays? American jazz superimposed over communist hearts--what could be more poetic" or symbolic of the hunger for intellectual freedom and creative expression.

For me, studying music made me a far better writer. It taught me a sense of pacing, rhythm, and that any composition—whether of words or musical notes—needs motifs that repeat, modulate, and evolve to a harmonious resolution. When I want to hear if a section I’ve written works, I read it aloud. If I stumble over phrases or I don’t sense a cadence, I know I need to tweak it.

Why are animals often so important to your stories?

Like any dog-lover, I know well the joy a dog can bring. My family has always taken rescue dogs, so I have also felt the touching moment when a previously abused or abandoned dog suddenly looks at us with trust and love. Something that was very important in Storm Dog. I’ve also had and marveled at the aura of wisdom surrounding cats, which comes into play in Louisa June.

Like any dog-lover, I know well the joy a dog can bring. My family has always taken rescue dogs, so I have also felt the touching moment when a previously abused or abandoned dog suddenly looks at us with trust and love. Something that was very important in Storm Dog. I’ve also had and marveled at the aura of wisdom surrounding cats, which comes into play in Louisa June.

I was delighted when I realized that it made all sorts of sense to feature the no-nonsense strength of horsewomen in a narrative about the Great Depression. Set in Virginia horse country during the devastating drought of 1932, Bea and the New Deal Horse is inspired by several real-life equestrians of that decade and is all about resiliency and the stunning matter-of-fact altruism so many Americans managed to hang onto during those harsh years.

Bea’s story also turned into a bit of a love song to horsewomen young and “old,” those strong-willed, slightly steely, demanding, but utterly devoted trainers who school teen riders to achieve the breathtaking symbiosis possible between horse and a well-practiced, hard-working rider. Their old-school feminism, fierce loyalty to those they care about, and unspoken sisterhood. I had been so impressed (and moved) by the camaraderie between my daughter and her teammates, their self-discipline, uncomplaining grunt work around the stable, watchful concern for their horses’ wellbeing, and absolute joy soaring over fences. Bea herself is modeled on those dedicated, brave teens.

In case you're wondering, I merely trail-ride, but became a proud volunteer groom, trailer-driver, and rally-coordinator. Bea and the New Deal Horse is probably my most Frank Capra-style novel, a cross of Seabiscuit and National Velvet in sensibilities and character arcs. One of my greatest joys to write.

Why is there French dialogue in Under a War-torn Sky and A Troubled Peace? I don’t speak French.

Because most American flyers didn’t either. When they were forced to bail out of their planes, they fell out of the sky onto territory occupied by German-speaking Nazis with their only hope for survival being French-speaking civilians. Including snippets of French lets you experience briefly (and only slightly) the discomfort, the confusion, even the terror those boys must have felt during WWII. The French strangers on whom they depended could just as easily have been collaborators as Resistance fighters. Also, those passages (which are always basically translated for you in the next paragraph) give you a chance to see how very clever you are. I purposefully chose French words that mirror English ones. Most times, you can figure out quickly what the French person is saying.

What influences your writing most?

My children, even now as adults! Gifted and imaginative storytellers, they are my muses, my first readers, and as a professional screenwriter/novelist and theatre director, they are particularly astute editors for character development, theme continuity, authentic dialogue, pacing, and meaningful, gripping plot twists. I get no “fat” or “vague” prose past them!

Both have traveled with me as I research my historical novels, help me gather facts and recognize what carries particular pathos or symbolism. They are incredible sleuths and scholars and the best of companions on these adventures.

When they were young, their interests and concerns sparked my choice of subjects. Sometimes they inspired the story itself. The Hunter and Stripe picture book series, for instance, started as bedtime stories for my son when he was dealing with some playground issues of peer pressure and competition. I increased the more comical and endearing aspects of Basil (the idealistic old tutor) in Give Me Liberty because my son found him so amusing. Vladimir, in Suspect Red, a well-read, jazz-loving, saxophone-playing, sizzling point guard is very like him—something I realized consciously only after creating the character. With Mathias in WALLS, on the other hand, I very consciously remembered and gave that character the lightning-quick grace and cunning of my son's dizzying footwork as a D-1 college soccer striker and winger.

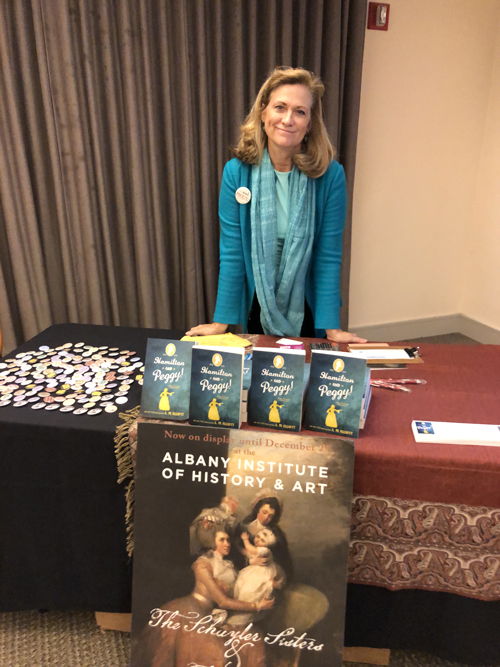

A great lover of art museums, my daughter was the one to introduce me to Ginevra de Benci, the young, proto-feminist poet in Leonardo’s first portrait, and the only work of his permanently housed in the U.S.—(in Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art)—the heroine of Da Vinci’s Tiger. The whip-smart and idealistic Natalia in Suspect Red is very like her. As is Simone in Truth, Lies, and the Questions in Between. My descriptions in Bea and the New Deal Horse of what it takes to ride and compete horses at a high level came from hours and hours standing at the railing watching and listening to her trainer coach her. And I came to know and be enthralled by the Schuyler Sisters—Peggy becoming the fascinating “wicked wit” heroine of Hamilton and Peggy!—because as a young theatre director my daughter absolutely had to see Hamilton and its impact on the paradigm of possibilities in theatre. I got to tag along! And viola, an idea for that novel was born!

Which do you enjoy writing most: picture books, novels, or nonfiction? For youth or adults?

I enjoy and grow as an author by having variety. That’s one of the glorious things about writing for a living—every day, every story is different. A writer is always learning.

As a journalist, among other things, I wrote about soccer star Mia Hamm, followed doctors who saved babies born three months too early, watched a choreographer create a new ballet, and profiled an extraordinary woman who’d been attacked, handcuffed, and thrown off a bridge into a river and survived. My covering “women’s issues” solidified my more feminist instincts, which has served me well in my biographical fiction like Hamilton and Peggy! and DaVinci’s Tiger. Being a reporter first really taught me how to spot a story, to interview/report for authenticity, to be grateful for editors, and to make a deadline. (Learn more in https://lmelliott.com/writing-and-research)

Researching my novels, I’ve learned—among other things—about flying airplanes; how young fifers and drummers were critical live-savers during battles; about 15th-century women artists, philosophers, and poets long forgotten by history; discovered an ordinary farmer who became a double-agent and saved us from disaster and defeat during the American Revolution; spy-techniques used by George Washington and French teenagers during WWII; and of women who refused to be cowed by Nazi cruelty and kept one another alive in concentration camps as well as those at home who welded ships that kept America afloat.

I’ve traveled centuries, marveled at the human spirit, found inspiration and warning, and tremendous hope in what is magnificent in us even as we fight our baser, more selfish and fearful demons.

There is a special joy in writing for teens—they have a way of cutting to the pith of a matter, brook no baloney (as my daddy would have said), and have not yet been conditioned to accept compromises or apathy. Their righteous indignation at the injustices of the world prods me as I write. I know to lace even dire moments or harsh truths with a thread of hope because young adults believe that if they try hard enough, keep to their moral compass, and think with compassion that they can make a difference in this world. Amen. I write in ways to encourage that.

(BTW, students often ask me how much money I make. I always answer that a writer is rarely rich monetarily, but she is certainly rich in spirit.)

Who is your favorite character?

Students almost always ask this and, I’m sorry, I cannot pick one over all the others. They are all precious to me in some way. But here are a few thoughts about those particularly dear to me:

For my WWII novels: Under a War-torn Sky, I’d like to have the courage and sophistication (and the wardrobe!) of Madame Gaulloise; I marvel at Henry’s tenacity and ability to care about others in the midst of war’s cruelties as well as little Pierre’s compassion, his hope. In A Troubled Peace, Claudette delights me with her fiery idealism and personality. I have a real fondness and admiration for the British evacuees Wesley and Charles, their pluck, resiliency, and droll sense of humor in Across a War-tossed Sea. With Louisa June and the Nazis in the Waves I had the chance to speak in the pictorial, Tidewater-love-of-anecdote manner of my father and his family, and really celebrate their deep love and respect of nature, the fierce devotion among a family's generations that was the way of rural life in the 1930s and 40s. Louisa June may be the most lyrical and observant of my characters, but she's also incredibly stubborn and feisty, and I love that about her. Her ancient, eccentric, wry, and cat-loving Cousin Belle makes me smile with her blunt opinions and championing of LJ. I honestly would hope for all young people to have that kind of a wise, attentive older relative in their lives.

I was so taken by the real-life Peggy Schuyler, her bodacious intelligence and "wicked wit" (as her peers called her), her brave devotion to her siblings and father, and her ability to face hard truths and life-threatening dangers. It was a true honor to recreate her in Hamilton and Peggy! (I also admit to falling a little in love with George Washington, Lafayette, and a philosophizing double agent named Moses Harris.

In Bea and the New Deal Horse, Mrs. Scott is an amalgamation of several smart, fiercely independent and opinionated older ladies I've had the privilege to know, love, admire, and be challenged by--so she is very dear to my heart. Bea breaks my heart with her sudden maturity, forced on her by the world's circumstances, and valiant protectiveness of her younger sister, Viv, who she calls (with a loving smile) a faery-child hellion. What's not to love about all three of those female characters? And oh, the courage of Malachi and the quirky, hopeful soul of the old stablehand Ralph.

I learned so much from Abbess Scholastica in Da Vinci’s Tiger, ached and dreamed with the poet Ginevra, and couldn’t help but be amazed by that real young woman’s defiant intellectualism and sense of self that sings through in the one remaining line of her verse—“I beg your pardon, I am a mountain tiger.” As soon as I unearthed that sentence I knew—I wanted to glean all I could about her!

In Give Me Liberty, Basil makes me laugh, Moses makes me cry, and Nathaniel reminds me of how much bravery it takes to grow up. I am very proud of him at the end of the book. Suspect Red is full of yearning, inquisitive, artistic young people I’d love to spend hours and hours listening to—and the siblings, Richard and Ginny, Vlad, and Natalia all have large dashes of my children’s personalities and interests in them. Walls characters, Drew and his sisters Joyce and Linda, allowed me to pay homage to all those military kids I knew as I grew up, who moved and adapted constantly in service to our country, often in very dangerous postings--like Cold War Berlin.

Storm Dog's sassy, idealistic Ariel takes me home to the hills of Virginia, the allure of a catbird’s song, the sheer delight in dance, the incantation of music, and the salvation of unexpected friendships. And how could I not be delighted with the country-philosopher and big-hearted Marcus and his piccolo-playing, reformed alcoholic, Revolutionary War re-enactor father?

So... I can’t pick one.... can you?

When do you write? Where do you write?

Mostly in the early morning and in my home office, which I am happy to report is sunny and serenaded by wrens and chickadees. Its walls are covered with photos of my children, our adventures together overseas, and their childhood artwork. So it is very conducive to creative thought, although it was never some quiet ivory tower. My training as a journalist makes me able to write whenever and wherever. I’ve outlined and edited on plane trips to visit them at college or waiting for their athletic matches and horse rallies, their plays, and concerts to begin. I email myself notes all the time when an idea hits me while running errands—otherwise I might forget them.

How long does it take you to write a book?

It depends. For my historical novels, typically it takes me about eighteen months, the longest work being the research. I can work faster if I need to, though. To catch the Hamilton wave, for instance, I got that assignment, researched, and wrote Hamilton and Peggy! in ten months. That was an insane, all-hands-on-deck, 24-7 marathon, though, that I wouldn’t recommend!

It depends. For my historical novels, typically it takes me about eighteen months, the longest work being the research. I can work faster if I need to, though. To catch the Hamilton wave, for instance, I got that assignment, researched, and wrote Hamilton and Peggy! in ten months. That was an insane, all-hands-on-deck, 24-7 marathon, though, that I wouldn’t recommend!

What slows me up during the writing phase is if I have a hole in my knowledge, which I have to stop and research. I hate that because I lose my rhythm! For A Troubled Peace, for instance, when I was writing a chapter that included Henry borrowing a bi-plane I realized in the middle of a paragraph, that I didn’t know how cranking the propeller would kick-start the engine or how to land it. Luckily, a very nice man at the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in New York answered my telephone call and explained.

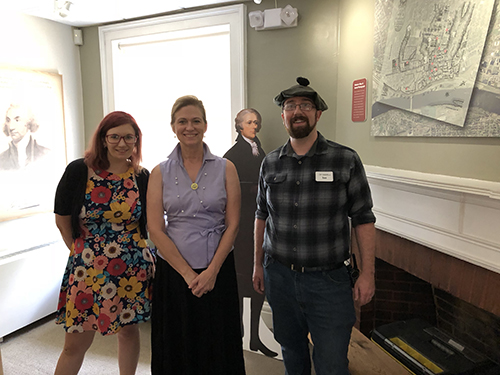

I am completely indebted to historians who generously share their vast knowledge, like the Schuyler Mansion interpreters who so graciously gifted me their expertise, meticulous research, and enormous patience with my constant questions.

At garden parties, over fresh-squeezed lemonade, they’d talk and talk in musical voices and long anecdotes. They talked of history – but not about dates, battles, or political figures.