[ Back to Historical Fiction ] -> [ Back to Hamilton and Peggy: A Revolutionary Friendship ]

Major Players

PEGGY SCHUYLER’S FAMILY, FRIENDS, AND ADMIRERS:

For our girl PEGGY please see my entry “How Much Is True” by clicking HERE

GENERAL PHILIP SCHUYLER

There are so many “supporting” founding fathers that Americans don’t recognize enough. Philip Schuyler is among them. It’s fair to say that without his foresight and deep knowledge of New York’s dense wilderness, his capacity for diplomacy, his cunning, and his stubborn loyalty to the cause, New York—and therefore possibly the Revolution—might have been lost to British forces.

Besides serving as commander of the Northern Army from 1775 to mid–1777 (one of only four major generals including George Washington) and as a New York delegate to Congress, Schuyler was also the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, responsible for negotiating war alliances with the six Iroquois nations. The Oneida, in particular, became vitally important allies to the Patriots, largely thanks to Schuyler.

Perhaps most importantly, Schuyler was probably the Revolution’s most skilled military intelligence and counter-intelligence officer. Out of their Albany home, Schuyler ran a critically important “black chamber operations” network of Canadian, Iroquois, and New Yorker spies and double agents. He gathered information on enemy movements and intentions through his scouts, informants, and by intercepting British communiqués. He and his staff would open, copy, and reseal these letters and then send them on to their intended recipients, who’d never know the information was compromised. Schuyler also fed his enemies false information through fake letters between him and George Washington. He was so dangerous in his spymaster capacity that a band of British soldiers and Loyalists invaded his house one night to try to kidnap him.

In many ways, Schuyler was Washington’s right-hand man. He detected conspiracies for surprise attacks in New York and adjacent northern states, guarded our vulnerable back door at the Canadian border, and found ways to supply the Continental Army, often out of his own pocket, when others left its soldiers to starve and freeze. He continued to do so even after his honor was publicly maligned by Congress and stripped him of his command—literally on the eve of the Saratoga battle he had prepared New Yorkers to fight.

Perhaps because I have lived most of my life in Virginia, which is so steeped in Revolutionary history, I was woefully ignorant of the cataclysmic nature of the conflicts tearing apart New York for eight bloody years. So much of the fighting was neighbor against neighbor, Loyalists against Patriots, bands of robbers from both sides against farmers and families, and American Indians who allied with the British against settlers living on the wilderness fringe. And then there was the terrifying invasion from Canada by an enormous British and Hessian army.

The Schuylers were right in the middle of it all.

I should start with two stories about a younger Philip Schuyler because they reveal so much about him, the close bonds the Americans and the British had before the Revolution, the very international complexion of the new nation, the fortitude of its women, and the largesse enemy officers could show one another in the midst of carnage.

Like George Washington, Philip Schuyler served the British during the French and Indian War. He became great friends with his commander, British General John Bradstreet, eventually even naming his firstborn son for him. After the war, Bradstreet remained in America, becoming a surrogate father/grandfather figure to the Schuylers. So much so, Schuyler was willing to sail to England on business for him, leaving his young wife Catharine to oversee the building of their Albany mansion, with three daughters all under the age of five. She was pregnant again with twins as well, who would perish shortly after their birth while Schuyler was absent.

On that voyage, the captain of Schuyler’s ship died. Schuyler took over the navigation because he was quite smart mathematically. That put him at great peril of being executed when the next mishap occurred—French privateers, pirates really, captured the ship. But Schuyler managed to negotiate for his life (and for the lives of the other British-born passengers) because he spoke French so fluently.

Once, during the French and Indian War, Schuyler and his unit had flushed the enemy off a tiny island in the watery regions of upstate New York. The French and American Indians retreated. They mounted a counterattack as Schuyler and his men were canoeing back to the main shore to join their company. In the midst of the crossfire, Schuyler heard a badly wounded French Canadian crying out in agony and begging not to be left there to die. The British soldiers with Schuyler ignored their enemy’s pleas. But Schuyler plunged into the waters, swam back to the island, lifted the enemy onto his back, and found a place he could wade across the waters, carrying him. The French Canadian lived. Years later, during the Revolution, he became a spy for the Americans out of gratitude for Schuyler saving his life.

This is not to say Schuyler’s experience fighting the French and their native allies made him an infallible military leader in the Revolution. Far from it. Like George Washington, Schuyler made many initial and disastrous mistakes. For instance, he masterminded the Patriots’ ill-fated 1775-76 campaign into Canada. He believed, as so many Patriots did, that French Canadians would want to join the Revolution to oust the British ruling their province. After initial success in Montreal, the siege of Quebec failed miserably. Schuyler was not there, detained in Ticonderoga by a raging fever and flare-up of his gout, a debilitating illness that plagued him throughout the war. So, it was Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery who ordered an attack in the middle of a blizzard. Yet, Schuyler was blamed for the debacle—the first of many Congressional attacks on his leadership.

Yet Schuyler’s first-hand, deep knowledge of upstate New York’s forests and lakes, born during his youth and honed by his soldiering during the French and Indian War, would prove invaluable. Schuyler knew exactly where and how to slow the march of Burgoyne’s British Army to a crawl—by felling trees to clog paths and destroying footbridges over bogs and streams. That allowed Schuyler time to beg for supplies, weapons, and reinforcements from Washington and to rally local militias, so that when the Patriots and Redcoats finally met at the Battle of Saratoga, the Patriots, for the first time, actually had superior numbers. The British also arrived exhausted, slowed and beset by Schuyler’s tangle of obstacles.

Congress replaced Schuyler with the ambitious and politically conniving Horatio Gates literally days before the Battle of Saratoga began. Why? The delegates blamed Schuyler for the surrender of Fort Ticonderoga to Burgoyne’s advancing army—despite the fact the subordinate officer who ordered the American evacuation saved the lives of those 3,000 American soldiers who were then able to fight and help win the watershed battle at Saratoga. After that victory, the French were convinced the American Revolution was viable and worth supporting.

Stoic and Old-World courtly, Schuyler would still attend the surrender ceremonies dressed in civilian clothes. He even invited the defeated Burgoyne and his officers to stay at his Albany mansion while the Americans arranged for their deportation back to England—despite the fact Burgoyne torched Schuyler’s country estate at Saratoga, completely destroying the home, mills, crops, and barns. Such ironies riddled Schuyler’s life. He mentored Aaron Burr, for instance, inviting the man who would eventually kill his beloved son-in-law to study the law by using Schuyler’s own private library. Before that, Burr would run against and unseat Schuyler from his U.S. Senate seat.

Above all else, Schuyler was a devoted family man, beginning his letters to his daughters with “my beloved child” and clearly fostering his daughters’ intellect, politically-informed conversation, and poised sophistication. For more on his marriage, see my next entry on Catharine Schuyler, whom Schuyler affectionately called “Kitty.”

https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/articles/victorySchuyler.htm

http://www.threerivershms.com/schuylermansion.htm

https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/01/plot-kidnap-schuyler/

CATHARINE VAN RENSSELAER married Philip in 1755 after a two-year courtship. Born to a land-wealthy Dutch aristocratic family, she was renowned for her beauty, described as “a lady of great beauty, shape, and gentility” and “delicate but perfect in form and feature, graceful in her movements, and winning in her deportment.”

But clearly, Catharine had her own mind and inner steel.

Schuyler was called back from the French and Indian War with some haste for their wedding. It seems Catharine was already four months pregnant—something that was not uncommon for brides during colonial times. During the course of their almost 50-year marriage, Catharine would survive twelve pregnancies and give birth to fifteen children (one set of triplets and twins). Seven died in infancy or childbirth, but Catharine raised eight to adulthood (five daughters and three sons). From the age of 21 to 47, Catharine was either expecting or recovering from giving birth and caring for small infants. She was pregnant with her final baby when Eliza and Hamilton married and was already a grandmother to Angelica’s young son and daughter.

Catharine managed Schuyler’s Albany mansion, its 80 acres of farmland, and the enslaved servants who worked within the house. She stood by her husband in success and failure, during two wars, many long separations, and both political victories and humiliations. She hosted a constant parade of visiting statesmen, military leaders, and foreign dignitaries. Later in life, visitors described Catharine as somewhat formidable—“A big Dutchwoman, with a rather serious disposition” said one French officer. Perhaps she was yet again pregnant and consequently feeling unwell during their visits! Or perhaps she was hesitant in conversation since her primary language was Dutch and she lacked a larger formal education. Certainly by that point, Catharine had faced a great many hardships that might have made her matter-of-fact and less impressed by political reputation or European titles.

Legend holds that she rode toward an advancing British army to burn wheat fields at their country estate in Saratoga, in order to prevent Burgoyne’s troops having the grain. An 1852 painting depicts the scene. While Schuyler had called on New Yorkers to burn their crops rather than letting the British take them, records don’t support the story of Catharine doing so at Saratoga. However, Catharine did indeed go to the house to gather as many provisions as her wagons could carry. There was a skirmish outside the house between Schuyler’s guards and Loyalists, and there was a real danger of her being taken hostage. She also endured housing the defeated Burgoyne, his staff, and their American guards pillaging her fields and stores!

In his letters, Philip always addressed his wife as “My Dear Love.” He was heartbroken when she died in 1803, and passed away himself a year later.

Sources:

http://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/guest-blog-the-women-of-schuyler-mansion (by Schuyler Mansion Historic Interpreter, Danielle Funiciello)

http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/11/catherine-van-rensselaer-schuyler.html

https://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/bios/vr/cavr.html

http://www.americanrevolution.org/women/women4.php

ANGELICA

So much has been written about Peggy’s scintillating oldest sister, Angelica, that I will refer you to sources listed below. But here’s a little about her marriage to John Barker Church (or John Carter as the Schuylers first knew him) within my novel’s timeline:

A commissar for the armies, Church/Carter had fled England either to escape gambling debts or retribution for a duel, and adopted the alias Carter. (He remained Carter throughout the war so I will refer to him as such.) In late 1776, Congress sent Carter and two other commissioners to audit Schuyler’s military accounts from the Northern Army’s failed attempts to conquer Quebec the previous winter. Despite what must have been a slightly adversarial stance with the Schuylers, Carter was elegant and charming enough to win Angelica’s heart during a time her father was besieged with setbacks and dangers. The mansion was in constant uproar with couriers riding in and out, each message they brought more dire than the last. Burgoyne’s invasion was on, Americans were scattering in his wake as the British seized Crown Point, Fort Ticonderoga, and Lake Champlain’s Skenesborough. Philip was also handed a resounding defeat in his campaign to be New York’s governor. In the middle of all that, Angelica eloped with a man her father distrusted and disliked.

Frankly, Angelica’s choice was perplexing. But despite his devolving into an overweight, carousing dullard, when Carter met Angelica—if an early portrait of him is to be believed—he was quite handsome, with enormous eyes and thick wavy hair. For a vivacious, brilliant young woman—who had grown up in New York City’s lively society and as a constant, pampered guest of the royal governor, Lord Henry Moore—Carter’s cosmopolitan aura would have been quite alluring. Perhaps his secretive past—gambling debts, a romance gone wrong, a duel—was exciting to her as well. After all, when she was an impressionable teenager, Angelica had witnessed the elopement of Lord Moore’s daughter and society’s aggrandizing of the girl by romanticizing her affair.

A dedicated Patriot, Angelica must have thought Carter would become an important player in the Revolution. He did provide critical aid to the cause by finding supplies for the French army. But he also profited from the venture, making a large fortune for himself. As such, Carter was a controversial character. At one point, Washington said that all profiteers should be hanged.

In 1783, Angelica and Carter left for Paris so he could collect payment for his services to Rochambeau’s forces. They then settled in London, where Carter readopted the name Church. He was elected to the British Parliament, while Angelica became a famed hostess. She was something of a muse to Thomas Jefferson (then ambassador to France) as well as to her brother-in-law Hamilton, writing letters to both that were filled with impassioned philosophy and political ideas, doled out in dazzling and affectionate language. She came back to New York on frequent visits, and her close, intellectually intimate relationship with Hamilton was always subject to gossip. Still, she and Carter/Church had five sons and three daughters, and Angelica seemed to delight in being a mother. Sometimes she refused to receive visitors if she were in the middle of a card game with her children.

It is said Carter/Church owned the pistols Hamilton carried to the duel that killed him—the same pair Hamilton’s son Philip died by. Burr had also dueled with Carter/Church in 1799, but both men survived that confrontation.

Sources:

http://thehistorychicks.com/episode-72-schuyler-sisters/

http://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/guest-blog-the-women-of-schuyler-mansion (by Schuyler Mansion Historic Interpreter, Danielle Funiciello)

https://www.monticello.org/site/blog-and-community/posts/and-when-i-meet-thomas-jefferson

https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/angelica-schuyler-church-32756.php

ELIZA

You don’t need much from me on this lovely, devoted woman, beautifully portrayed by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton and written about constantly.

Please see my Bibliography https://lmelliott.com/book_landing_page_historical/hamilton-and-peggy-revolutionary-friendship/bibliography) and below for links to comprehensive sources on her life:

http://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/guest-blog-the-women-of-schuyler-mansion (by Schuyler Mansion Historic Interpreter, Danielle Funiciello)

http://thehistorychicks.com/episode-72-schuyler-sisters/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-elizabeth-hamilton-deserving-musical-her-own-180958214/

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/11/08/what-eliza-hamilton-left-behind

http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2010/08/elizabeth-schuyler-hamilton.html

http://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov//albany/bios/s/elschuyleranb.html

A historian’s lecture on Eliza Hamilton’s time at Albany after marrying Hamilton:

https://www.c-span.org/video/?430924-1/eliza-schuyler-hamilton-schuyler-mansion-

You can read for yourself Alexander’s beautiful letters to Eliza at:

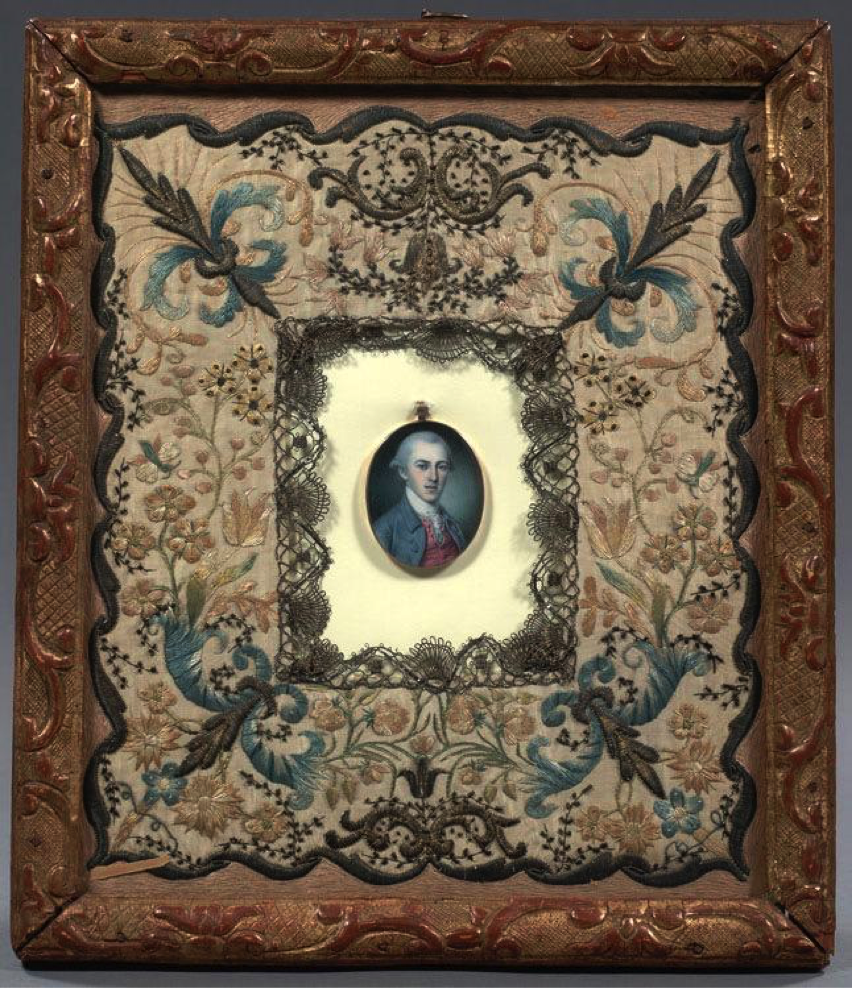

This is the silk mat Eliza embroidered to surround Hamilton’s portrait for their wedding, described in my novel. (Held by Columbia University)

ALEXANDER HAMILTON:

Thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda, our $10-bill founding father has been raised from relative obscurity to virtually a household name these days. So, as with Eliza, I won’t bore you with a general bio. I will simply say that reading dozens of Hamilton’s letters—his simmering love notes to Eliza, bantering letters to friends and fellow aides-de-camp, and eloquent official appeals and communiqués—was a wondrous experience. His poeticism and awed passion for life and love; his Revolutionary fervor and idealism; as well as his insecurities and bluster fairly shimmer off the pages. For more about what clearly was an immediate and heartfelt affinity between Hamilton and his sister-in-law Peggy—the binding thread of my novel—see my entry Peggy: How Much Is True.

I love this little seen miniature of a young Hamilton:

See Eliza’s entry above for the link to Hamilton’s love letters. (Also go to my bibliography to find a host of well-done biographies on him in addition to Ron Chernow’s famous one.)

Other general links:

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/alexander-hamilton/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alexander-Hamilton-United-States-statesman

PBS: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=36U6wZXVBPc

Hamilton expert Joanne Freeman:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cH-74jKEkU0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=476-srhPG5M&t=182s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OQHgqCyYgpU&t=750s

Marquis de Fleury

It was in a passing, playful reference to Peggy in Hamilton’s September 3, 1780 letter to Eliza that I discovered the Marquis and the fact there was some romance brewing for Peggy. Hamilton teases his soon-to-be bride that Peggy might beat her to marriage: “When your sister returns home, I shall try to get her in my interest and make her tell me of all your flirtations. Have you heard any thing more of what I hinted to you about Fleury? When she returns, give my love to her and tell her, I expected, she would have outstripped you in the Hymenal line.”

Given the date of that letter, Peggy must have met Marquis Francoise-Louis Teissedre de Fleury in Newport, Rhode Island, where it makes sense she was staying with Angelica and her husband Carter, then commissary for the newly landed French army. I had to really dig to learn much about Fleury. Like Lafayette, he came to the States on his own to volunteer with the Continental Army. And like hundreds of other Frenchmen, his enormous contributions to the Patriot cause are largely forgotten—even though Fleury was one of only eight individuals honored by Congress during the American Revolution with a commemorative medal.

Born in Southern France, Fleury joined the French Army at age nineteen, serving in Corsica before sailing to America. At first, Congress didn’t know what to do with the flood of idealistic French officers, but Fleury was soon a captain with the Continental’s corps of engineers. Well-trained and a natural leader, Fleury eventually rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He served (and was wounded several times) at Yorktown, Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and the horrific siege of Fort Mifflin.

His extraordinary bravery at Stony Point is what earned him a Silver Congressional Medal of Honor. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne (nicknamed for his wild daring) masterminded the seemingly suicidal attack on the British Hudson River stronghold, 30 miles north of NYC. Heavily armed and manned, the fortress was surrounded by a marsh and sat atop 150-foot cliffs the Redcoats had spiked with spears they’d cut from the surrounding forest. The Continentals went at night armed only with bayonets to guarantee silence during their approach. About 40 men were charged with “the forlorn hope,” clearing a path through the cliffs’ spikes for the patriots to crawl through and up to the battlements. Surprise seemed their only hope of survival. But as they waded through waist-high waters, the Patriots were spotted, the alarm sounded, and the Redcoat watch opened fire. In the barrage, Wayne was shot, enduring a gaping wound along his scalp, but the charge went on.

Fleury was the first over the battlement. He rushed to the flagpole as desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued, and yanked down the British flag, shouting at the Redcoats to surrender and the Patriots to show mercy. The Americans took 543 prisoners, with only 78 men killed on both sides.

A British commodore wrote of Fleury’s courageous charge: “The rebels had made the attack with a bravery never before exhibited.” Fleury showed “a generosity and clemency which during the course of the rebellion had no parallel. Instead of putting them to death, [he] called to them to throw down their arms” and they could expect to be given quarter. This humanity was particularly remarkable since some British commanders in previous battles had slaughtered wounded Patriots who had already surrendered.

Ingenious as well as brave, Fleury wrote General Washington in January 1778 a marvelously enthusiastic letter, in awkward English, describing self-propelled, exploding fireboats he hoped to launch into the British fleet anchored in the Delaware River and threatening Philadelphia. Washington applauded Fleury’s “zeal for the Public service” and suggested using “some desperate fellows” and “the greatest secrecy and caution” to “make the experiment.” As far as history knows, nothing came of Fleury’s clever design or plan. (Perhaps they were discouraged knowing the failure of “the turtle”—a fantastical eight-foot-long, one-man, egg-shaped submersible—technically the first submarine used in warfare—whose designer pedaled through the waters of New York Harbor to try to attach an exploding mine to the hull of a British warship.)

Each year since 1989, the United States Army has awarded individuals who make significant contributions to Army Engineering the de Fleury Medal, a replica of the one presented the Frenchman in 1779.

When Peggy met him, Fleury would have been thirty-one and a bit legendary. His Newport host described him as “sociable, jocose, and very agreeable in conversation, of a free, liberal turn of mind in matters of religion.” It really bothered me that I could never resolve what happened between the two of them after Fleury mentioned his hopes of marrying Peggy in a letter to Hamilton. All my research would divulge is that after the war, Fleury returned to the French Army, which awarded him the Order of Chevalier de Saint Louis for his part in the capture of Yorktown. He fought in a variety of campaigns from South America to India to Europe. (Read the novel to learn what I speculate happened between Peggy and him given the facts I could find! There are a few more details about Fleury in my afterword but I don’t want to give them away here.)

There is no portrait of Fleury to be found, but this is the uniform he would have been wearing while serving with Rochambeau’s Army in 1780.

Sources:

https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/11/top-5-foreign-continental-army-officers/

RICHARD VARICK:

While Varick was not kin, he certainly shared the closeness of family bonds during his service as aide-de-camp to General Schuyler. A native of Hackensack, NJ, Varick had just finished studying the law in NYC when fighting broke out. He immediately joined the militia and in July 1775 was appointed Schuyler’s secretary. Unofficially, Varick also took on the difficult, life-or-death responsibilities of quarter and muster master, finding ways to fill the Northern Army’s ranks, stomachs, and muskets. He remained faithful and loyal to Schuyler during all his political troubles, only reluctantly going to Gates’ staff when commanded to during the Battle of Saratoga. There, Benedict Arnold snapped him up to be his aide-de-camp. (Arnold admired Schuyler and thought Gates—who never left his tent during the battle—a fool and coward.)

It was Varick’s letters from the battlefield to Schuyler and his constant ending, “please to give my best to Miss Peggy” that made me speculate Varick had quite the crush on her.

After Saratoga, having aligned himself to Arnold whom the then triumphant Gates detested, Varick left the army and returned home to practice law. Philip Schuyler had resigned his commission as general and Arnold was inactive, recuperating from a terrible leg wound he’d suffered during Saratoga. No longer a colonel in the Continental Army, Varick nonetheless wished to serve. He joined his local militia as a lowly private taking his turn standing watch every other night in Hackensack, NJ.

Varick would again join Arnold as aide-de-camp when the general was appointed commander of West Point in 1781. Little did Varick know of the treachery Arnold was planning—to turn over West Point to the British. Arnold’s treason was discovered and poor Varick suspected of aiding him. Eventually, he was cleared, thanks largely to Schuyler’s lobbying.

Schuyler is also probably responsible for the next and most important leg of Varick’s Revolutionary journey. From July 1781 until December 1783, when the war was officially ended, Richard Varick served as George Washington’s recording Secretary. He stayed in Poughkeepsie, organizing and editing thousands of Washington’s letters, dispatches, journal entries, and battle proposals that arrived in trunks under escort of His Excellency’s personal guard. It is entirely fair to say that Varick and the diligent scribes he oversaw so carefully to produce the forty-four volumes of Washington’s wartime papers housed in the Library of Congress are responsible for our modern-day knowledge of the Revolution.

He married Maria Roosevelt in 1786, was mayor of New York City from 1789–1801, and lived until 1831.

Sources:

http://www.sunypress.edu/p-5293-richard-varick-a-forgotten-foun.aspx

https://www.mountvernon.org/

DR. JOHN COCHRAN

I have to admit Peggy’s uncle Johnny Cochran was one of my favorite discoveries. How could you not love a man who writes letters calling a nitwit, self-impressed officer a “nincompoopa?” Schuyler’s brother-in-law, friend and physician to George and Martha Washington, Cochran became the fourth Director General of the Continental Army’s Medical Department. He was instrumental in inoculating the troops against smallpox at Valley Forge and had crossed the Delaware River with the ragtag Continental Army to attack Trenton. It was at his home in snowbound Morristown—the army’s winter encampment during the brutal winter of 1780—that Alexander Hamilton met and wooed Eliza.

With a legendarily buoyant and cheerfully outspoken personality, Cochran was a favorite with Washington’s “family” of aides-de-camp. He was an excellent dancer and singer, nicknamed “Dr. Bones” because of a farcical song he loved to sing with a refrain “bones, bones, bones.” Lafayette was convinced Cochran saved his life when he removed a musket ball from his leg on the Brandywine battlefield and was particularly devoted to the doctor. (Cochran also saved Lafayette from a bit too much partying at Angelica and Carter’s home in 1778, when Washington had dispatched the young Frenchman to return to King Louis XVI and beg for French troops and aid.) Cochran seems to have been universally beloved.

Sources:

http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/served/cochran.html

http://www.threerivershms.com/cochranfriend.htm

GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON

Connected through friendship and agreeing to be the youngest Schuyler child’s godfather, George Washington’s affinity with Philip Schuyler went beyond their work for liberty. So, I include him here. I should admit that I kind of fell in love with GW as I researched.

Here are my reasons:

His legendary stoicism and calm was not natural to Washington. He evidently had quite a volatile temper during his youth that he learned to muffle—mostly. Therefore, his composure was hard-won and a practiced, stunning act of self-control. He’d had a difficult childhood. GW’s father died when George was only 11-years-old, leaving the majority of his property to his sons from his first marriage. As a result, George and his five younger siblings and mother were left stretched for cash so that unlike most founding fathers, GW was not able to attend college, be taught Latin or Greek as most of his peers were, or sent abroad to study as had been his half-brothers. He never seemed bitter about it, and adored his half-brother Lawrence. What George knew as a country gentleman planter, businessman, and surveyor, were mostly self-taught. He was always self-conscious about the fact he could not speak French, a large reason for his dependence on Alexander Hamilton, who was fluent. GW’s mother was harsh, demanding, and judgmental—not the least impressed by her son’s ultimate role as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and publicly critical of what she felt was abandonment by her eldest son.

When he was only 17-years-old, GW taught himself the necessary geometry to become a land surveyor and win an appointment to measure the wilderness of western Virginia. What he learned traveling those wilds, often guided by American Indians, may have been the best education possible for a commanding general whose main survival strategy during the Revolutionary War would be the cat-and-mouse game he had to play with the better-trained, equipped, and numbered British troops. Traversing the backcountry, GW developed an uncanny ability to read impending weather—his sense that a dense fog was coming, for instance, prompted him to prepare a night evacuation that allowed his decimated army to slip silently and invisibly across the East River from Brooklyn in 1776. When the British army awoke, expecting GW to surrender, thereby ending the war before it really began, they found the Patriots vanished.

GW quickly realized he needed something else to keep his soldiers alive and for his hit-and-run plan—to wear down the British by constantly moving, avoiding European-style all-out battles—to work. Spies. Informants. Carefully laid counter-intelligence to confuse the British and get them off his trail.

GW became a spymaster.

Enter the Culper Spy Ring, an espionage unit combining the expertise of military tacticians with brave civilians, overseen by a Continental dragoon named Benjamin Tallmadge (code name John Bolton), who had grown up on Long Island with many of the spies he recruited. GW himself was part of the ring, “Agent 711.”

Washington would often send out and handle his own agents, who reported to him exclusively to avoid leaks. Along with Philip Schuyler, who ran an incredibly successful “black chambers” operation out of his mansion throughout the war (see Schuyler above), GW popularized the now customary intelligence tactics of code names, ciphers, cryptic messages, invisible ink, "dead drops," and other methods of deception. Without this unique type of warfare, the Revolution, in all likelihood, would have failed miserably.

As I researched the novel, I was stunned by the constant bickering and jockeying of his aides and subordinate officers for GW’s attention and favor, the number of assassination plots, and the political collusions to unseat him from command. Many men would have thrown up their hands in dismay and bitterness and gone home. Hamilton, in fact, parted from Washington in a tantrum of anger and resentment about GW refusing to give him a field command. (GW needed Hamilton’s brilliance as translator and political/tactical strategist at headquarters.) His resignation left GW horrendously understaffed, especially in negotiating with Rochambeau’s troops. Hamilton refused both GW’s apologies for his own curtness and hot anger during the argument, which Lafayette delivered, and appeals to his patriotism from his new father-in-law. Even so, GW never lost sight of Hamilton’s talents and eventually rewarded him with a command at Yorktown and a vitally important role as Treasury Secretary in his presidential administration.

Through it all, GW was HUMAN. He LOVED to dance, for hours at a time, to play catch, to wrestle, and to romp with his herd of dogs, whom he blessed with ridiculously affectionate names like Sweetlips and Madame Moose. He was an astoundingly graceful and symbiotic equestrian. And when he loved people he was absolutely devoted to them. “My old man,” Martha Washington affectionately called him—obviously he did not take himself too seriously!

George Washington loved, he hurt, he laughed, he joked, he feared, he faltered, but he stubbornly held to his convictions and dragged a new nation to its feet. I highly recommend dipping into Mount Vernon’s wonderful website: (http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/#personal or http://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/) to experience for yourself the anecdotes related there that so humanize the “father of our country” we too often represent in cold marble.

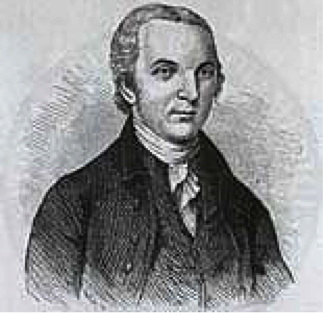

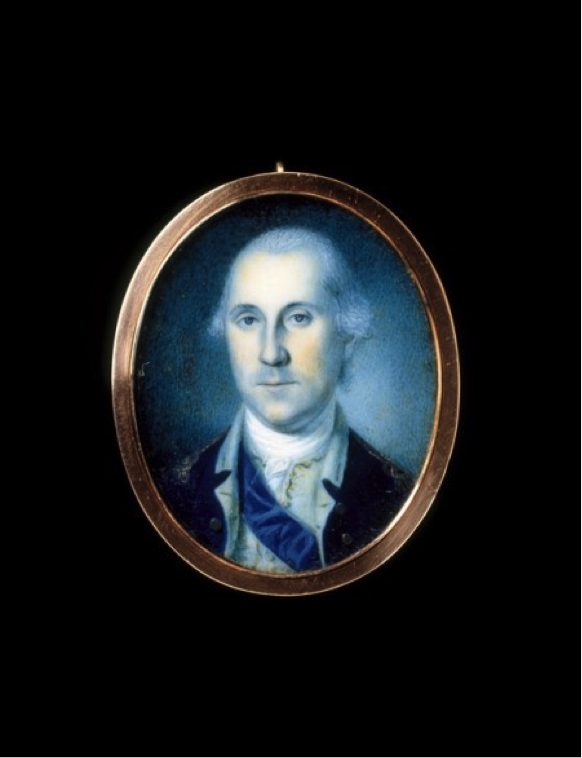

Below is the miniature Martha had painted of her husband in 1776 and which she wore around her neck or held in her hand:

For information about his work as spymaster and the Culper Ring see: https://www.benfranklinsworld.com/episode-065-alexander-rose-washingtons-spies-the-story-of-americas-first-spy-network/

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/benjamin-tallmadge/

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/culper-spy-ring/

You might enjoy watching AMC’s TURN: WASHINGTON’S SPIES

Martha

I would be remiss not to talk briefly about the much beloved “Lady Washington,” as Continental soldiers fondly called her. George married the affluent 26-year-old widow with a young son and daughter in 1759. They never had their own children, but George was a devoted stepfather, particularly with Nelly. He was broken hearted when she died suddenly, at age 17, probably from an epileptic seizure.

Martha had a warm, light-hearted nature and provided a wonderful balance to George’s more reserved public persona. A petite, modest, and relatively sheltered woman, Martha would never have sought the limelight on her own, and seemed perfectly content to live a quiet country gentry life. But when her husband answered the call to serve, she gave him a gentle, positive support that sustained him throughout the many hardships and disasters of the war.

Despite her fear of travel and the real danger of British and Loyalist bands capturing her to hold as hostage, the then middle-aged Martha followed her husband often to his constantly moving headquarters and withstood the brutal winter encampments with him. She spent at least half of the long eight years of the Revolution by his side. She knitted, sewed, nursed, and raised money for the troops, herself donating the equivalent of $20,000. She endured many sorrows, including her only son dying of camp fever at Yorktown.

Sources:

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/martha-washington/