Laura's Blog

A Long Song for George Washington

February 19, 2018

I admit to totally falling in love with George Washington as I wrote Peggy’s story. I have included below my entry on him and Martha in the “Major Players” entry on the novel’s landing page to tell you why.

One of the gifts I wanted for Christmas was to revisit Mt. Vernon with my son who researched Washington for me. (See his February 16th blog of his favorite GW things) Entering, I was struck once again by Washington’s astounding modesty and sense of self-contained and polite decorum.

After winning the Revolution, after his presidency, Washington does not fill Mt. Vernon with trophies or memorabilia of his triumphs. He does build a new greeting room, anticipating the flood of visitors he would have to entertain as the country’s most beloved and important statesman. But he decorates it in a way to pay homage to farming. The molding has motifs of agricultural tools, grapevines, shafts of wheat. The paintings are of rivers—the Hudson and the Potomac. His commissioned marble mantelpiece doesn’t contain images of the battles he won—but a flock of sheep and a boy hitching horses to a plow. In their bedroom, he and Martha hung portraits of their grandchildren.

Given the noise of today, I long for Washington’s quiet and steadfast devotion to our people, his ability to recognize that others will tell his story, so there is no need to bray or take down others to elevate himself. For me, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s portrayal of Washington is one of his most brilliant and moving brushstrokes. I tear up every time I listen to “One Last Time.” And Chris Jackson’s performance of him is what gave me chills.

This version of it, in front of President Obama and V.P. Joe Biden is no exception:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uV4UpCq2azs

GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON

Connected through friendship and agreeing to be the youngest Schuyler child’s godfather, George Washington’s affinity with Philip Schuyler went beyond their work for liberty. So I include him here. I should admit that I kind of fell in love with GW as I researched.

Here are my reasons:

His legendary stoicism and calm was not natural to Washington. He evidently had quite a volatile temper during his youth that he learned to muffle—mostly. Therefore, his composure was hard-won and a practiced, stunning act of self-control. He’d had a difficult childhood. GW’s father died when George was only 11-years-old, leaving the majority of his property to his sons from his first marriage. As a result, George and his five younger siblings and mother were left stretched for cash so that unlike most founding fathers, GW was not able to attend college, be taught Latin or Greek as most of his peers were, or sent abroad to study as had been his half-brothers. He never seemed bitter about it, and adored his half-brother Lawrence. What George knew as a country gentleman planter, businessman, and surveyor, were mostly self-taught. He was always self-conscious about the fact he could not speak French, a large reason for his dependence on Alexander Hamilton, who was fluent. GW’s mother was harsh, demanding, and judgmental—not the least impressed by her son’s ultimate role as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and publicly critical of what she felt was abandonment by her eldest son.

When he was only 17-years-old, GW taught himself the necessary geometry to become a land surveyor and win an appointment to measure the wilderness of western Virginia. What he learned traveling those wilds, often guided by American Indians, may have been the best education possible for a commanding general whose main survival strategy during the Revolutionary War would be the cat-and-mouse game he had to play with the better-trained, equipped, and numbered British troops. Traversing the backcountry GW developed an uncanny ability to read impending weather—his sense that a dense fog was coming, for instance, prompted him to prepare a night evacuation that allowed his decimated army to slip silently and invisibly across the East River from Brooklyn in 1776. When the British army awoke, expecting GW to surrender, thereby ending the war before it really began, they found the Patriots vanished.

GW quickly realized he needed something else to keep his soldiers alive and for his hit-and-run plan—to wear down the British by constantly moving, avoiding European-style all-out battles—to work. Spies. Informants. Carefully laid counter-intelligence to confuse the British and get them off his trail.

GW became a spymaster.

Enter the Culper Spy Ring, an espionage unit combining the expertise of military tacticians with brave civilians, overseen by a Continental dragoon named Benjamin Tallmadge (code name John Bolton), who had grown up on Long Island with many of the spies he recruited. GW himself was part of the ring, “Agent 711.”

Washington would often send out and handle his own agents, who reported to him exclusively to avoid leaks. Along with Philip Schuyler, who ran an incredibly successful “black chambers” operation out of his mansion throughout the war (see Schuyler above), GW popularized the now customary intelligence tactics of code names, ciphers, cryptic messages, invisible ink, "dead drops," and other methods of deception. Without this unique type of warfare, the Revolution, in all likelihood, would have failed miserably.

As I researched the novel, I was stunned by the constant bickering and jockeying of his aides and subordinate officers for GW’s attention and favor, the number of assassination plots, and the political collusions to unseat him from command. Many men would have thrown up their hands in dismay and bitterness and gone home. Hamilton, in fact, parted from Washington in a tantrum of anger and resentment about GW refusing to give him a field command. (GW needed Hamilton’s brilliance as translator and political/tactical strategist at headquarters.) His resignation left GW horrendously understaffed, especially in negotiating with Rochambeau’s troops. Hamilton refused both GW’s apologies for his own curtness and hot anger during the argument, which Lafayette delivered, and appeals to his patriotism from his new father-in-law. Even so, GW never lost sight of Hamilton’s talents and eventually rewarded him with a command at Yorktown and a vitally important role as Treasury Secretary in his presidential administration.

Through it all, GW was HUMAN. He LOVED to dance, for hours at a time, to play catch, to wrestle, and to romp with his herd of dogs, whom he blessed with ridiculously affectionate names like Sweetlips and Madame Moose. He was an astoundingly graceful and symbiotic equestrian. And when he loved people he was absolutely devoted to them. “My old man,” Martha Washington affectionately called him—obviously he did not take himself too seriously!

George Washington loved, he hurt, he laughed, he joked, he feared, he faltered, but he stubbornly held to his convictions and dragged a new nation to its feet. I highly recommend dipping into Mount Vernon’s wonderful website: (http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/#personal or http://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/) to experience for yourself the anecdotes related there that so humanize the “father of our country” we too often represent in cold marble.

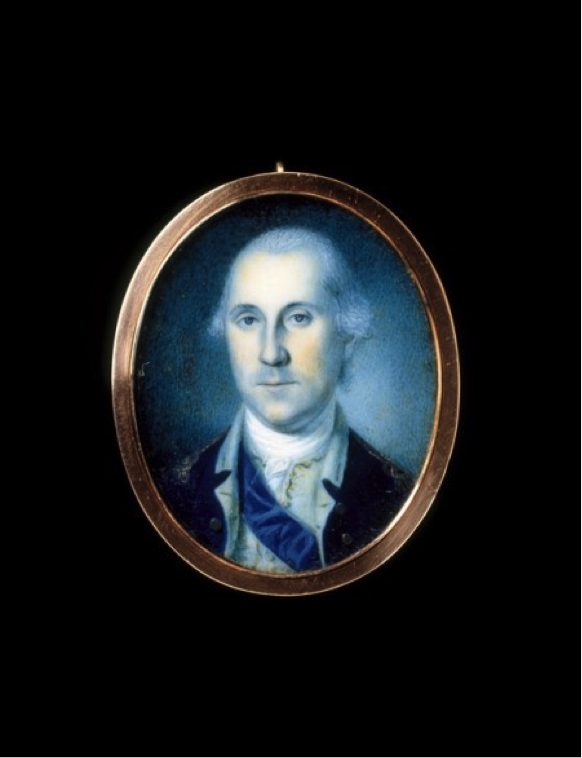

Below is the miniature Martha had painted of her husband in 1776 and which she wore around her neck or held in her hand:

I would be remiss not to talk briefly about the much beloved “Lady Washington,” as Continental soldiers fondly called her. George married the affluent 26-year-old widow with a young son and daughter in 1759. They never had their own children, but George was a devoted stepfather, particularly with Nelly. He was broken hearted when she died suddenly, at age 17, probably from an epileptic seizure.

Martha had a warm, light-hearted nature and provided a wonderful balance to George’s more reserved public persona. A petite, modest, and relatively sheltered woman, Martha would never have sought the limelight on her own, and seemed perfectly content to live a quiet country gentry life. But when her husband answered the call to serve, she gave him a gentle, positive support that sustained him throughout the many hardships and disasters of the war.

Despite her fear of travel and the real danger of British and Loyalist bands capturing her to hold as hostage, the then middle-aged Martha followed her husband often to his constantly moving headquarters and withstood the brutal winter encampments with him. She spent at least half of the long eight years of the Revolution by his side. She knitted, sewed, nursed, and raised money for the troops, herself donating the equivalent of $20,000. She endured many sorrows, including her only son dying of camp fever at Yorktown.

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts