Laura's Blog

Guest Blog: Historical Galentines!

February 12, 2018

“Friendship, that Love's Elixir, that pure fire

Which burns the clearer ‘cause it burns the higher”

Friendship by Katherine Philips in correspondence with The Society of Friendship, 1664.

It’s almost Galentine’s Day! The day set aside to celebrate female friendship and sisterhood. The fictional holiday, created by Amy Poehler’s character Leslie Knope on Parks and Recreation in 2010, very quickly became a nonfiction phenomenon. Women of the twenty-first century have a lot of love to show for their gal pals, but what about women from the eighteenth century? Margaret “Peggy” Schuyler and her sisters definitely did not celebrate Galentine’s Day; so what was friendship like for them? Who were Peggy’s friends, and how might they have shown their love for one another?

It is hard to imagine, with the value now placed on female friendship, that there was once a time when the words penned above by Katherine Philips(1632-1664) to her mostly female literary circle were considered controversial. However, according to classic philosophers like Aristotle, only men were capable of forming friendships. Because of this old way of thinking, Katherine Philip’s assertions of love and affection for her female friends did not really catch on during the seventeenth century. Luckily for Peggy(1758-1801), the American Revolution was not the only new idea in the air during the eighteenth century. In fact, there was almost a complete reversal in “friendship is only for men” thinking. In 1772, for instance, the fictional mother in Sarah Maese’s book The School tells her daughter that because men are busy most of the time they “have their intimacies and connexions, but real friendship is seldom found amongst them.” There were still many people that believed that women weren’t capable of genuine virtuous friendships but, obviously, those people weren’t women.

Peggy would have been growing up at a time when more and more female authors were writing books and stories[i] in magazines and newspapers, many of which described female friendship. Most novels in the eighteenth century were meant to tell young people how to behave – or how not to behave. Therefore, books about female friendship show how a good friend was supposed to act. In “The Bracelets”, published in 1787, a girl’s teacher compares the good qualities of two friends, Cecelia and Leonora:

“you are good-natured, Cecilia, for you are desirous to oblige, and serve your companions; to gain them praise, and save them from blame; to give them pleasure, and relieve them from pain: but Leonora is good-tempered, for she can bear with their foibles, and acknowledge her own; without disputing about the right”

The ideal of friendship has not changed much, however, the composition of friendships and how girls’ expressed friendship still would have looked a little different.

Today, people often make friends who are from different places and backgrounds than themselves. For both women and men in the eighteenth century, having friends outside of one’s social class was discouraged. For Peggy, who was from a wealthy, well-educated, and “genteel” family, her friends would have also been wealthy, well-educated, and genteel. In eighteenth century Albany, where elite families maintained their power and wealth through intermarriage, this also meant that almost all of Peggy’s friends would have been related to her. It is very likely that Peggy considered her two oldest sisters to be her best friends, since they were close in age and spent the most time together, and that her other friends were cousins. We know, for instance, that Kitty Livingston, a close friend of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, shared great-great grandparents with the Schuyler sisters, making them third cousins.

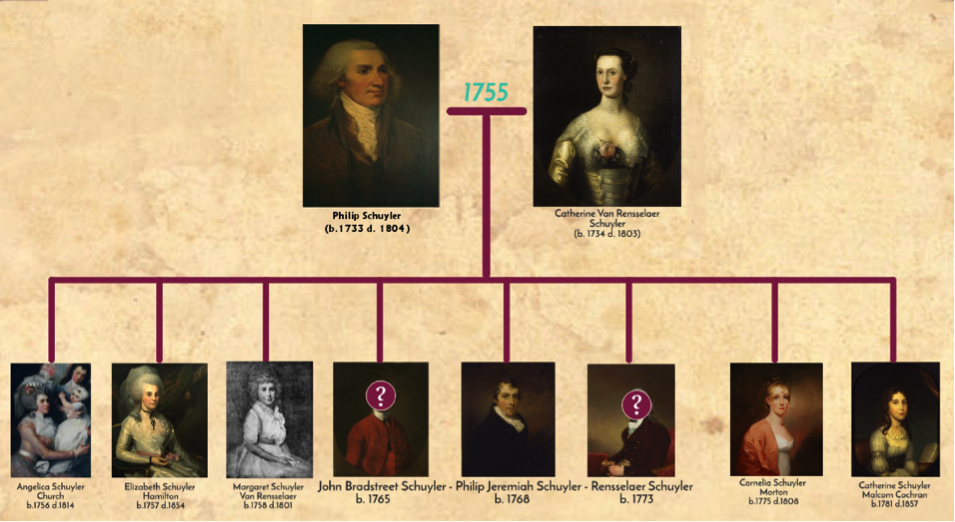

Family tree showing Peggy’s parents and siblings (there are no known paintings of John B. or Rensselaer Schuyler). Peggy was close in age with her sisters Angelica and Elizabeth. From letters and documents, the girls seemed to be emotionally close as well. Sisterhood and friendship were often seen as the same- your sisters were your friends, and you friends were your sisters.

Peggy was probably also friends with Kitty Livingston, but historians do not know who her other friends were, or how they talked to each other. Why? While Peggy’s sisters Angelica, Elizabeth, and later Cornelia and Caty moved around a lot, Peggy stayed close to home. She grew up in Albany, NY, married a man from Albany – Stephen Van Rensselaer, and because she was often ill, she did not travel much. Because of this, most of her friends were probably local, and since her friends were local, she did not have to write letters in order to communicate with them. For historians, no letters or other documents means that we can only guess at what Peggy’s friendships were like.

Left: A piano forte in the formal (southeast) parlor at Schuyler Mansion in Albany, where Peggy lived from around eight years old until her marriage in 1783. Most eighteenth century girls learned an instrument or singing as part of their education. Right: The northeast parlor at Schuyler Mansion set up for tea and conversation. This may have been the room where Peggy and her sisters entertained visiting friends.

However, by looking at girls like Peggy, we can make some pretty good guesses. Wealthy girls in eighteenth century New York made many of their friends through their family, churches, and, later in the century, schools. Girls and women went “calling” at each other’s homes to visit their friends. When they got together they talked, had tea or ate meals, read stories, journals, or newspapers to one another, played games, or worked on sewing and other projects. Sharing or showing off one’s talents by playing music and singing was also a popular form of entertainment. Like today, younger girls played with dolls, cards, and board games, while older girls practiced dancing and went for walks. The Schuylers had a large garden next to their home where Peggy might have taken her friends to get exercise and fresh air.

In the true spirit of Galentine’s day, female friends of the eighteenth century also did a lot of gift-giving. Gifts included flowers, ribbons, fabrics, and handmade items that showed off skills like embroidery or painting. Later in the century, Peggy and her friends may have become familiar with “secret” meanings behind flowers so that they could send each other messages with a bouquet.

A miniature painting of Alexander Hamilton by Charles Wilson Peale, in an embroidered frame made by Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton; Columbia University.

Receipts for Peggy’s school supplies show that she took a particular interest in drawing and painting. In her classes, she learned to paint flowers and miniature portraits on glass. For budding artists like Peggy, it was popular to paint “miniatures”; portraits of one’s self or one’s friends which were usually between 1.5”-4”. Girls gave them as gifts, or carried on chains or ribbons and used them like wallet photographs today - to remember far away friends or to show off one’s friends and family to new acquaintances. Alexander Hamilton introduced himself to Peggy by letter after seeing just such a ‘miniature’ of her, drawn by Elizabeth:

“I have had the good fortune to see several very pretty pictures of your person and mind which have inspired me with a more than common partiality for both. Among others your sister carries a beautiful copy constantly about her elegantly drawn by herself”

Sewn and embroidered items were also popular gifts. Sometimes these were purely aesthetic pieces, but more often, they were functional items. Pockets - which at that time were a separate article worn tied around the waist under a lady’s top skirt - are a popular example, though decorated handkerchiefs, mitts (fingerless gloves), purses, and other small worn items also became gifts between friends. These gifts gave girls the opportunity both to show their affection for their friends and to practice and show off artistic skills that were a part of their refined education.

An embroidered pocket from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Despite the beautiful decorations, these pockets were worn under a ladies skirts; slits at the waist of the skirt allowed the wearer to reach through and access the pockets.

We might not be embroidering pockets for our friends this Galentine’s Day, but we can still remember the friendships of Peggy, her sisters, and her friends as we celebrate our own friendships and sisterhood. We can give handmade presents, have tea, read together, or sing songs. Ultimately, eighteenth century friendship was really about sharing the skills that are important to you and appreciating and acknowledging the skills of the women in your life who mean the most. Happy Galentine’s Day!

Danielle Funiciello is working towards her PhD in History at SUNY Albany. She is a research fellow at the New York State Museum and a seasonal historical interpreter at Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site in Albany.

[i] See: Haslett, Moyra. "'All pent up together': Representations of Friendship in Fictions of Girls' Boarding-Schools 1680-1800." Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Volume 41, Issue 1, 2018: 81-99.

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts