Laura's Blog

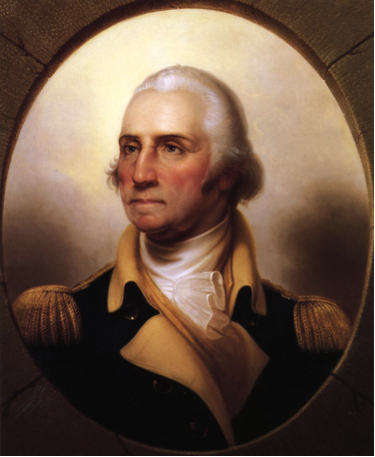

George Washington Orders a St. Patrick’s Day Celebration

March 16, 2018

Tomorrow I get to celebrate St. Paddy’s Day with Schuyler Sister singers and an Irish harpist at Scrawl Bookstore in Reston. (Ya’ll come!! It’s going to be such fun!) Among other PEGGY tidbits, I’ll be sharing the details of the special St. Patrick’s Day to which George Washington treated his troops in 1780. And it was VERY special—the only day off the Continental Army had that entire year!

At sunrise on this day in 1780, it was already snowing. AGAIN. By nightfall, George Washington would record an accumulation of 9 inches—on top of what was already on the ground. The winter of 1779-80 is still the most brutal ever recorded in American history. There were 28 separate snowstorms between November and April 1st. Snowdrifts reached six feet high and just didn’t melt. The Morristown/Jockey Hollow encampment was essentially buried and cut off, roads impassable and food stores depleted. We always hear about the horrors of Valley Forge’s winter encampment. But Morristown was worse. Shivering in log cabins hastily built during a nor’easter that would make this month’s seem mild, soldiers could go for days with nothing to eat other than nibbling bark off trees, officers even having to kill their pet dogs to eat to survive.

Washington knew his soldiers needed a lift-me-up. Bad.

So he issued an order that the next day, March 17th, “a day held in particular regard” by the “brave and generous people” of Ireland, would be a day of rest for everyone. He cancelled all work and fatigue duties. GW hadn’t even done that for Christmas or New Year’s Day.

The Irish in camp—(and there were many: 25 % of Continental soldiers were Irish born or of Irish descent, including seven out of eleven generals in command of American brigades)—began the day with band music. Then they broke into a spontaneous parade, wading through the snow, under a flag sporting an Irish harp and the caption calling for the Independence of Ireland. They happily consumed a hogshead of rum purchased by the commander of the Pennsylvania Division, (nearly half of its ranks were Irish), but they heeded GW’s order that “the celebration of the day will not be attended with the least rioting or disorder.” They must have been so joyful to have something to warm their toes that the army basically retired to their cabins.

Washington’s order reveals two things about him: his sincere compassion and concern for his men and their morale. It also shows the beginning of the consummate and clever statesman GW was becoming. Not all Continentals loved the Irish. They were often derided for being short in stature and speaking with a brogue others couldn’t understand. GW showing this amount of respect and regard for them, their history, and their fighting spirit helped silence some of that prejudice.

His actions were altruistic, we hope, but also practical. If one out of four of his soldiers were Irish, GW better make them feel included in the New World’s patriot cause. In general, the Irish and Scotch-Irish were the largest immigrant group by far coming to the colonies in the 1700s. They had a deep-seeded resentment and defiance of the British, who had taken over their lands, charged them exorbitant rent for what they had once owned, and further impoverished them by dictating they could only export their crops and goods to England. Ben Franklin had hoped to fan open revolt against England by printing a tract in 1778 and smuggling it into Ireland, in which Franklin expressed sympathy “to the good people of Ireland” for the “misery and distress to which your ill-fated country has been so frequently exposed.” He reassured them of America’s desire to help however we could once we gained our own independence.

In his St. Patrick’s Day proclamation, GW was also careful to praise the mounting political unrest in Ireland and its Parliament’s protests against the British Crown’s policies. He knew that trouble just across the narrow Irish Sea from London could be an important distraction to the British that would benefit his own battle against them.

Actually, March 17th already held a special place in GW’s heart. Four years earlier, in 1776, it was the date of “Evacuation Day,” when after 11 months of being under siege, Bostonians watched 9,000 Redcoats and 1,000 Loyalists board their ships and leave for Nova Scotia. GW’s general orders for that March 17th set the word “Boston” as the challenge password and “St. Patrick” as the counterword for safe re-entry to the city.

Don’t you wonder if some Continental in Boston shared this wonderfully irreverent Irish blessing with GW as they watched those 120 British warships and transports disappear over the horizon:

May those who love us, love us;

And for those who don't love us,

May God turn their hearts;

And if He doesn't turn their hearts,

May He turn their ankles,

So we will know them by their limping!

Other Blog Posts

Click Here to See All of Laura's Blog Posts